Free Bird

Jodi Cash’s father passed away at the end of 2020. Ever since, the scenes of their relationship in her memory have been a movie she can’t stop watching.

When I walk through the streets of Barcelona, I have to laugh about how much my dad would love my new home: the boats out to sail, the sun-beaten tourists, the cover bands, the strange treasures hidden in local gift shops. It reminds me of St. Augustine, Florida’s Old Town, where he spent some of the best and what proved to be the final years of his life. (The kinship here is obvious: Established by the Spanish in 1565, St. Augustine wears its history as more than just a facade for tourists.) Both are still inhabited by pirates and ghosts. Now, my dad is among the latter.

He slipped away quietly at the end of 2020. And since, scenes of our relationship, nestled deep in my memory, have been like a movie I can’t stop rewatching.

If I were to write that movie, it would open with my sister, Meghan, and I lying with our dad on his couch in Ft. White, Florida. In this scene, we’re 6 and 7 years old, wearing his T-shirts as our nightgowns. We’re in the single-bedroom cinder-block house that he rented to be close to us and our mom again. The sky glows mint green. The screen door pops open and shut as the pressure changes and the wind blows, carrying a heavy storm. The blinds are shut and the house is dark, save for the glow of the TV in the corner of the living room. On it, VH1’s “Behind the Music” is telling the story of Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Meghan and I are transfixed as the episode reaches its climax. My dad is asleep, knowing well what happens: Three days after the band released an album with an image of themselves engulfed in flames on the cover, their plane crashed in the middle of nowhere, Mississippi. Lead singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist and singer Steve Gaines and his backup-singing sister Cassie died, alongside one of their road managers and the two pilots.

Cue “Free Bird.” Recorded four years earlier, they wrote the greatest song about leaving ever recorded just to tell their own story. The surviving members had to go on, carrying those lyrics — a plea for acceptance — with them.

That era of fast and hard living in rock ’n’ roll history was something my dad taught us all about, and this was just one lesson. A musician himself, he used these stories to justify his own choices in the name of rock. The song lyrics he sang — ranging from covers of Lynyrd Skynyrd to the Allman Brothers to the Eagles and beyond — told us all we needed to know about drinking too much and mixing the wrong drugs, about rehab, heartbreak, life on the road. My dad was born a ramblin’ man.

His life looked a lot like those songs he sang at bars and restaurants around the Southeast. But we had a special place in his set. When we came to his gigs, he’d bring us onstage one at a time to sit on his lap while he played our respective songs: “Brown-Eyed Girl” for Meghan and “Jody Like a Melody” for me. He’d ask us who was the greatest entertainer who ever lived and we’d point to him. Then he’d send us around to tables with his tip jar, and we’d tell whatever patio patrons watching him that night about our dreams of seeing Disney World, and they’d fork out some ones, maybe a five, or even a twenty-dollar bill. He’d let us count the cash and then he’d give us our cut.

That era of fast and hard living in rock ’n’ roll history was something my dad taught us all about, and this was just one lesson. A musician himself, he used these stories to justify his own choices in the name of rock.

Often using “A Boy Named Sue” as his doctrine for parenting, he told us we’d thank him someday for the gravel in our guts and the spit in our eye. He taught us how to cuss. He taught us how to fight. And he endowed us with his own golden rule: When in doubt, he said, we should imagine what he would do and do precisely the opposite. While other parents might have thought these lessons unsuitable skills for two little girls, he wanted to know that we would be okay without him around.

This preparation took on a more literal form, too. When we were tiny, he invented a game called Dead Dad, in which he would lay on the floor face down with his mouth open and his eyes rolled back. Meghan and I would push him and kick him and scream, “Daddy, get up!” And he’d let us provoke him until he’d finally grab hold of us and threaten to make us nap with him, right there on the floor. Really, it was his way of entertaining us in his strung-out state. He’d play a show in Atlanta and drive through dawn to Ft. White to be there when we woke up. It did the trick; we thought he was hilarious.

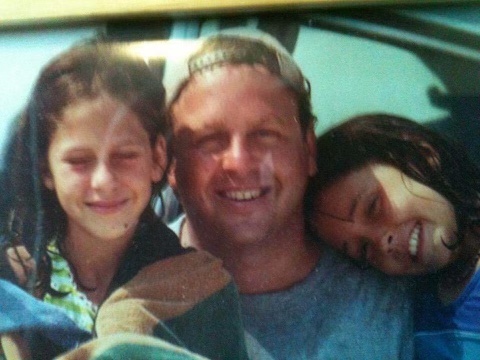

He was not, by any measure, a normal dad. The three of us — he, Meghan, and me — took pride in that, even when our relationship grew complicated as my sister and I became adults.

Frequently, after recounting some disastrous romance or blowup with a bandmate, he’d ask if I planned to write a book about him and then would offer to die so that I’d have an ending. We’d both laugh.

We rehearsed saying goodbye many times. A few heart attacks and other incidents meant that he took more than one critical ride to the hospital in the last decade and a half. He’d call to say how much he loved us; how proud he was, and I’d reciprocate, telling him how grateful I was that he was my dad.

I missed a call from him in the second week of December 2020. He didn’t answer when I called back. I missed another one from his best friend Stacy a few days later.

When I returned Stacy’s call, his words were brief, but kind.

Your daddy is gone. I’m so sorry. I’ve lost my best friend and a confidante. I love you girls; please tell Meghan for me.

He gave me the name of the funeral home and told me that he’d be there waiting when we got to St. Augustine.

Meghan had just woken up when I told her the news. In a few foggy moments that morning, our lives changed.

Days followed in a painful haze. We went through my dad’s things, most of them sentimental: photos of our family, of my dad as a little boy. A poem Meghan wrote about him in the first grade. A letter my mom wrote to him after their divorce. And in his wallet, beneath guitar picks and some change, I found a note I’d written him with song requests. I’d given it to him the last time we were together, less than two months before.

A strange series of events pulled us together that October.

My husband, Gresham, and I meant to be in Europe that fall — that’s where we started the year. Soon after leaving Atlanta for Barcelona, COVID-19 broke out and we found ourselves locked down.

Those days in Barcelona were much like being on a film set — the sweeping old world cityscape was empty, aside from the essential workers who were left to occupy what looked like choreographed routes. At that moment, we were insulated from the suffering brought on by the pandemic, and we quelled what worries we did harbor with new friends we made among our neighbors. We watched their lives from our balcony like vignettes as the seasons slowly changed.

Our experience was, to be honest, romantic. Stuck in the first destination of what was supposed to be a journey across Europe, we found a lot in Barcelona that made us want to stay: Flocks of parakeets swept through our block like a green flash. Shadows took shape as the sun rose from behind our building and set in front of it. Heat radiated up from ancient, labyrinthine city streets that led to the cool Mediterranean Sea. But come September, our provisional visa scenario — brought on by the pandemic — would no longer hold. We had to go home.

Home had taken on a nebulous meaning in the time we were away. We’d already said goodbye to Atlanta, so we located ourselves in Gulfport, Florida, where, alongside our dear friend and co-director Ethan Payne, we’d been shooting a documentary film called The Green Flash since 2017. After years of driving down from Atlanta to shoot interviews with a wily old maritime marijuana smuggler and the people who shape his life, we were finally ready to begin post-production. So we packed up our van and headed to Florida.

Ethan, Gresham, and I holed up in a house lovingly named Parrot Park. Our groovy landlords Edie and Matt gave us a great rate. They “could understand the artist thing.”

The house was aptly named. It felt a little like we’d been dropped into the Florida-glorious, 1970s-soaked movie we were making, with its terrazzo floors, walls painted in tropical colors, jungle-floral upholstered furniture, and the framed portraits of parrots and other beach birds hung throughout. Outside, a live oak shaded the house with its huge gnarled branches, from which ospreys called every morning and geckos chirped every evening. We’d sit in the backyard at night and watch a family of opossums descend from the branches like a staircase and march across our fence one by one.

I knew the person who would love our spot more than anyone was my dad.

I called him from a surf competition we were shooting in Cocoa Beach. He joked about coming down to crash it. Lucky for me, he said, he had a gig in St. Augustine that he couldn’t miss.

My dad was a professional musician all his life, but it was in St. Augustine that he formed what persisted as his musical identity. The first time he lived there, he was healing from the hurt of a failed marriage with my mom. From his apartment, a block or two from the beach, he’d walk beside the ocean to meet his best friend Stacy in the gazebo they called The Hawk’s Nest. While Stacy rented beach chairs to tourists, my dad would talk to him about big visions and heartache and write songs about both. There, he formed his band Henry and the Seahawks, inspired by that breezy lifestyle on Anastasia Island.

The second time, he was recovering from a mental break. Brought on by the pressure of making an album alongside some of Nashville’s most esteemed producers and session players, this put his career on hold for a while. But on the other side of rehab, he made his way back down to St. Augustine.

He rebranded his act as Henry Joe Solo. On patios of Old Town’s restaurants and bars and on the beaches of A1A, his fans and tourists would clamor, sunburned and hungry, to see him sing four-hour-long sets featuring all the hits: Marshall Tucker Band, Johnny Cash, Gordon Lightfoot, Glen Campbell — you name it.

So in that unexpected October back on U.S. sand, when he told me that he wouldn’t bust into our shoot in Cocoa Beach, but he had a gig in Tampa later that month, I was thrilled. We made a plan to see each other then.

When my dad pulled into the driveway of Parrot Park a few weeks later, it was the first time I’d seen him since his brother’s — my Uncle Todd’s — funeral in New York the February prior. We embraced. I was comforted to find that he smelled like he always did — a sweet mix of Polo Blue tinged with mildew — the result of playing shows every night in the soggy Florida heat. I leaned into the familiar weight of his huge arms. He gave me a rose that had been dyed Seahawk blue, which he bought at a gas station on his drive over from St. Aug, he told me.

He took one look at the house and deemed it vibey, the ultimate endorsement in a lexicon shared between him, Meghan, and me. He demonstrated the meaning of this descriptor, decorating the various one-bedroom houses and apartments he lived in over the years with Seahawk-blue LED rope lights, lava lamps, candles, sea shells, driftwood, and nautical artifacts he’d found in beachfront stores.

He gawked at Ethan’s monitor where Premier Pro was open. We’d been arduously combing through footage that was starting to look more like our own lives with every day that Florida seeped into our skin. It’s like you’re making a real movie, Joey, he said to me.

We took him on a tour of the town that we’d come to love as we filmed it. We watched the sunset on Treasure Island. We feasted on peel-n-eat shrimp at The Wharf. And we took him to see The Sea Bean, a sailboat we’d bought for cheap on Craigslist, anchored in Big Bayou. We drove through downtown Gulfport to admire the way it’s lit up at night.

He asked Gresham and me if we’d go back to Barcelona, and we said yes—as soon as we could get our visa applications together and processed. We told him that if anything stood in our way, maybe we’d just pack up our van and drive across the country. He volunteered himself to join us no matter which direction our adventure headed.

Back at Parrot Park that night, the four of us jammed for hours. My dad played all our requests. Gresham gave the songs texture on electric guitar. Ethan sang harmonies. I tried to keep up, so proud to show my dad that I could finally keep up on acoustic guitar.

He left for his motel with his set well rehearsed.

After a morning of working on the film, we arrived for the second half of my dad’s set at Rick’s on the River. He was in his zone: He had his tip jar set out with a bandana tied around it on a stool next to the one on which he sat. As I’d been well trained to do, I made a scene of placing a crisp twenty in the jar and handing him a note on which I’d listed the songs I wanted to hear: “Highwaymen,” “Pancho & Lefty,” “Southern Cross,” “A Pirate Looks at 40.” Anything by America or The Allman Brothers for Gresham. He hugged me and set about playing those songs.

He ended with “The Highwaymen.” This was a favorite of my sister’s and mine since the days when he would sing it to us while we were crammed together in the front seat of his Ford Maverick, which we called The Bomber. He bought it for 200 bucks cash from someone in AA. (He paid too much — that thing spent more time on the side of the road than on it.) To make Meghan and me laugh (and to distract us from the absence of heat, A/C, and functioning windows in The Bomber), he’d adeptly impersonate each of the four original “Highwaymen” as he drove us from Florida back to Stockbridge, Georgia, where we moved after my mom remarried.

We all sang the last line with him that night in Tampa, I may simply be a single drop of rain, but I will remain. And I’ll be back again and again and again and again and again… He let his voice trail off and he smiled. He thanked the crowd and introduced himself like it was a stadium show. Then he came offstage to sit with us.=

He reveled in our enthusiastic review of his performance. He let me count the cash in his tip jar. We shared a meal and then said he had to get back to St. Augustine, where his beloved dog Banjo awaited in the tiny house they lived in behind his landlord Clyde.

We helped him break down and load up. He gave me a long, long hug and kept finding ways to divert our goodbyes and keep us from leaving. Gresham reassured him that we’d see him again soon. We parted ways.

The next month our crew had reached a stopping point. Ethan returned to his life in Atlanta. Gresham and I planned our next stop in Nashville, where we’d stay with Meghan and her fiance Richard, while we tried to determine how and when we could get back to Barcelona.

Hurricane Eta hovered over the Gulf Coast as we packed our things up at Parrot Park. I texted my dad an update on our plans: He asked us to reorient our route and come through St. Augustine on our way to Tennessee. I said we needed to keep moving, especially with the storm rolling in, but that we’d visit him in St. Augustine soon. He responded with a heartbreak emoji and said I like you bein’ a Floridian.

Eta turned the sky mint green and sent the rain flying sideways as we precariously crossed the Howard Frankland Bridge. We pressed on as waves topped the retaining wall. I wondered whether the storm would pass over to the east coast of Florida and where my dad might go if it did.

Our next trip to St. Augustine wasn’t what I expected that day when we drove through a hurricane. It was cold and bright and my dad was gone. We held a tiny ceremony for him on Anastasia Island. We displayed his guitar and his photo on the beach in front of The Hawk’s Nest. A few of the musicians he’d played with for decades performed his songs. We all wept and told stories. The wind whipped down the beach carrying his spirit.

I’ve lived the year since trying to be brave, trying to honor the life my dad wanted for me. Gresham and I kept our word and drove our van across the country and back. We brought my share of Daddy’s ashes with us and would laugh and cry at the songs we suspected him of queuing on the radio.

We took refuge back in Gulfport for a while, lucky to return to Parrot Park. I clung to the beauty of being back in the last space we shared with him. I went looking for his courage inside myself, while we learned to sail and to surf. I’d think about him every time I timidly slung my first surfboard, named The Bomber, into the water. I’d paddle out in search of him and get caught in the breakers. When I was too beaten and exhausted to search anymore, I’d let the tide pull me out to where the water is calm and its surface unbroken by waves. I’d start to look again and find only my own reflection.

Sometimes my dad shows up in my dreams, even now that I lay my head in Barcelona again. He’s always laughing, like he just got busted in a crowd where he didn’t think I’d see him.

I reflect often on that cold morning when we said goodbye to him in St. Augustine. We could feel him hidden in the crowd at Salt Life, where the staff who cherished his weekly shows hosted an event in his honor. I hoped he was watching as one of his fans drilled a plaque for him into a palm tree in front of the restaurant while crying and smoking a cigarette tucked in the corner of his mouth. I met many people whose lives my dad had touched through his music and his own special brand of ministry. The refrain was the same: He always made time for them, to listen and love them, no matter what they were going through. One such young friend, whose concerts my dad used to attend at a nearby school for the visually impaired, laughed as we spoke and told me that my dad was right there. She pointed into a gap in the crowd.

And as we were leaving St. Augustine that day, “Free Bird” came on the radio.