In which our Culture Warrior heaves anchor and explores a new album of sea shanties, among other oddities along the passage.

Hark back now to the heady days of the 1980s, when haircuts were horrors, shoulder pads essential, and the lowly guitar declared all but dead in the wake of a turntablist and synthpop tsunami. Sales sank to pre-Elvis lows; Fender and Gibson were on the ropes. Nobody, lamented the guitar press, was bothering to learn “real” instruments anymore.

Fast forward a few decades and, evidently, things were never as bad as they seemed. The ranks of seriously accomplished guitarists circa 2022 boasts literally hundreds of melt-your-face shred beasts, players who play "Flight of the Bumblebee" faster than you can hear and armies of string technicians with more technique than most pre-1980 players could imagine. There are third graders on YouTube better at Eddie Van Halen tapping than EVH ever was, for crying out loud.

Consider 44-year-old guitarist Shane Parish, born and raised in south Florida, a ten-year resident of Asheville, and currently based in Athens, Georgia. One of his online bios declares he is “devoted to universal music, so his practice and listening habits grasp in all directions.” No surprise then that his playing career follows the same nomadic compass.

It is hard to pin down a precise number, but Parish has around 50 albums bearing his name (or the surname Perlowin, which he changed to Parish in c. 2014). They range across through-composed, high-intensity, arhythmic math rock, to solo acoustic and electric excursions, to fully improvised sets with the likes of percussion wizard Tatsuya Nakatani or guitarist Wendy Eisenberg. Parish’s albums appear on the crème de la creamy crème of independent labels: Cuneiform, International Anthem, Dear Life, John Zorn’s Tzadik. But unless you are one of those music geeks who haunts these corners of the internet machine (mea culpa), you likely have not heard his music.

With the recent release of Liverpool, it is time for that to change. Liverpool is a collection of instrumental arrangements of sea shanties for filtered through the lens of a 21st century cultural omnivore with a guitar in his hand.

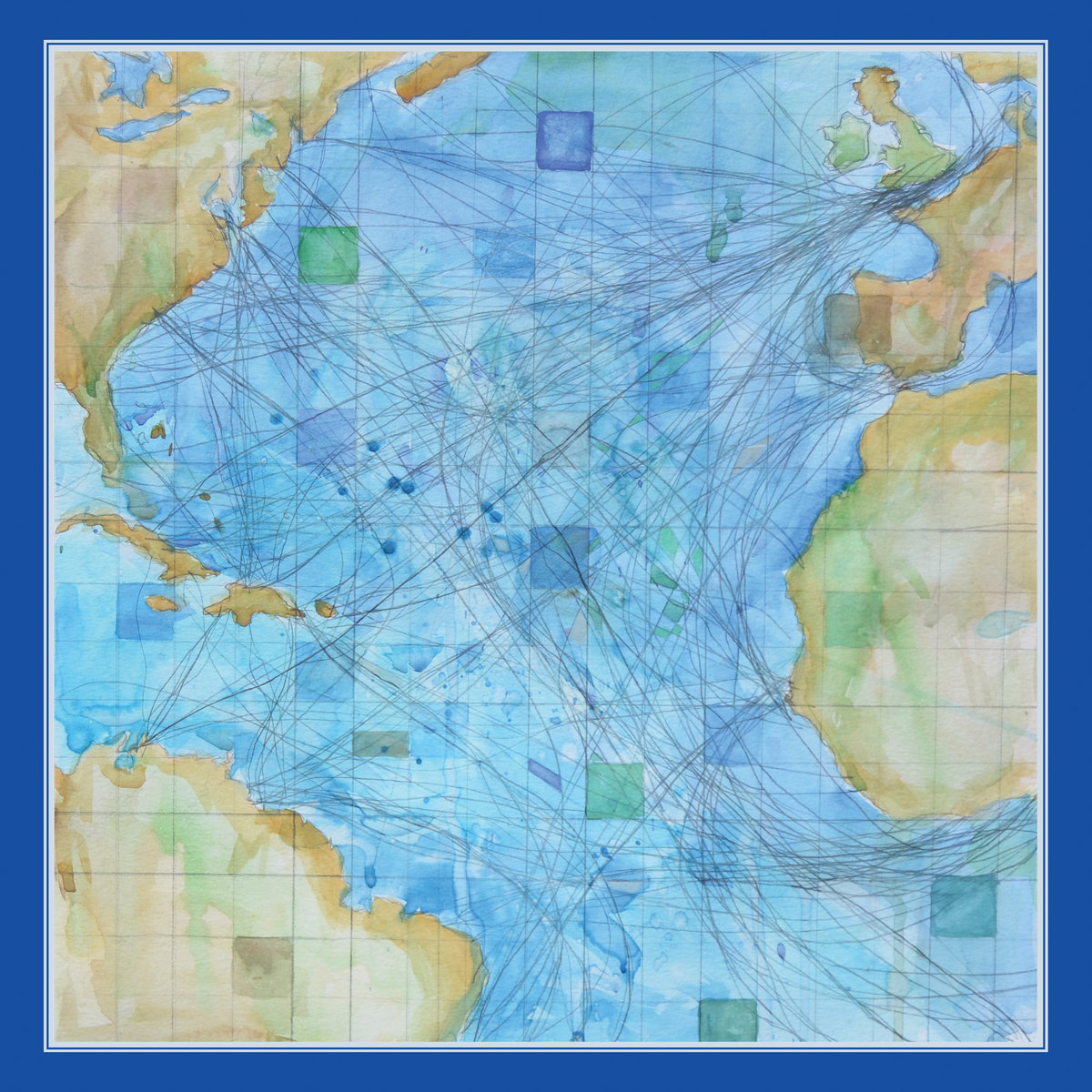

Sea shanties are maritime work songs, believed to date back as far as the 1400s, that regulated a crew’s labor rhythm and passed the time during the tedium and terror of life on the high seas. Given the world-encircling nature of the maritime trade, it is quite possibly the first true world music, with influences as far flung as West Africa, the East Indies, coastal Europe, the British/Gaelic isles, and parts of what was then known as the Orient. With sailor hands full of rope and handspike, shanty songs were unaccompanied, relying heavily on call and response forms. Most known shanties date from the 1700s to late 1800s, when mechanization replaced work crews.

And in one of those “wow, I did not see that coming” episodes, sea shanties have literally blown up the internets over the past year after a Glaswegian postman named Nathan Evans posted a TikTok of “The Wellerman,” a New Zealand whaling ballad c.1860-70. He copped a gazillion views and quit his job. Sea shanties, man. Who knew?

Anyway.

Most known shanties date from the 1700s to late 1800s, when mechanization replaced work crews.

Two Decades of Study

Parish first gained recognition with the prog/punk band Ahleuchatistas. Pronounced "AH-LOO-CHA-TEES-TAS” — a mashup of the Charlie Parker title “Ah-Leu-Cha” and Zapatistas, a Mexican socialist political movement — the band’s now-defunct website explains it as “musical and social revolution wrapped into single coinage. Movement and the constant outstripping of itself are what unifies all the sounds under this single name.”

A take-no-prisoners outfit, relentless and staggeringly precise in its anarchy, imagine a loud, fast lovechild of King Crimson and the Minutemen. This track from their 2003 debut On the Culture Industry is a great example.

In addition to the prog/punk proto-anarchy of Ahleuchatistas, Parish’s style encompasses straight classical guitar, Mississippi John Hurt fingerstyle blues, and the scraggle/skronk angularity of Captain Beefheart. He frequently drops solo interpretations of Charles Mingus, Sun Ra, Erik Satie, and Kraftwerk tunes.

And my favorite, Alice Coltrane’s “Journey in Satchidananda.”

Parish’s YouTube channel is packed with nuggets like this along with fascinating instructional clips that offer a glimpse of the kind of guitar teacher Parish might be. (Thanks to the intertubes, Parish has students all over the place, from first pluck beginners to established pros looking to inject something new in their playing.)

Along about 2014, Parish and his wife, artist Courtney Chappell, became parents. Like any good new parent, Parish took time to assess and recapitulate, which for any musician must include a probe of one’s musical impulses. He took up acoustic guitar almost exclusively and found himself immersed in the Fireside Book of Folk Songs and P.W. Joyce’s compendium of traditional Irish tunes.

This led to a flurry of albums, including a 14-volume set of 147 tunes from the Fireside Book. Notable among this burst are 2016’s Undertaker Please Drive Slow (Tzadik) and 2020’s Way Haul Away: A Collection of Fireside Songs. Audacious as hell, Parish kicks off Undertaker with Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” one of the most mournfully beautiful and revered tunes in the country blues canon.

Parish originally planned Liverpool as an acoustic affair to match Undertaker and Way Haul Away. He refined the arrangements for a year, but a few weeks before recording he ran the material on electric with drummer Michael Libramento. And lo, it was good. Naturally, this demanded radical rearrangement. Luckily, the management of Dear Life Records took this one-eighty in stride.

Here’s a look/listen at his approach to the windlass shanty “Randy Dandy O”:

Despite the shift to electric, I view Liverpool as completing a triptych alongside Undertaker and Way Haul Away. An encompassing, wide-angle snapshot of a singular artist at this specific moment, it fits comfortably in the American Primitive category (so named by the late guitarist John Fahey to describe his own work). But like most genres, it is descriptive and misleading at the same time.

‘Primitive’ can mean ‘primary source’; it also implies uncultured simplemindedness and lack of refinement. This music’s originators are hardly the unsophisticated rubes of caricature; most are serious archeologists and players of highly developed technique. Parish fits this mold with a rigorous practice regimen and deep commitment to exploration.

Through it all, Parish never forgets that melody remains paramount. An A-B listen to two versions of the shanty “Haul Away Joe” demonstrates this credo.

The solo acoustic version is pastoral, a lilting take that could almost serve as a child’s lullaby. On Liverpool, an E-Bow-driven electric guitar with drum/bass foundation offers a starkly different mood and timbre. Still, fealty to the melody stands.

A few weeks back, Parish posted this tweet:

This is a big year for me musically. Not sure if the career will follow. But, the music is definitely up and up after some years of incubation.

— Shane Parish (@shaneparishgtr) February 16, 2022

In a subsequent tweet, he wrote, "I'm on a decades-long arc developing some of this shit."

In a phone interview not long before the album's release, Parish told me: '“If you're actually going to execute something the workload is pretty significant. There needs to be discipline, a routine that I have to maintain. You know, you don't get to stop at this point. There's no rest. It's like a you're a ballet dancer, you know. You have to stretch and warm up and then hit it for a while, and hit it again. Otherwise, you're going to be rusty and you're not going to be able to perform on that level. So there's a lot of work that's gone in and continues to go in on the details. Then I want to play free. That's the thing. I want to be free on it. I want to turn off all that shit, all the rigor of it and, okay, now it can be expressive.”

Parish is one of those musicians who persists in the absence of fame and fortune. A dedicated father who teaches a full slate of students to make his daily bread, he nevertheless maintains that relentless discipline of refinement and discovery that marks any serious and committed artist. One who evidently plans to become that geezer picking in a garden or dive bar somewhere.

In a world going - or maybe all the way gone - mad, I find this inspiring. This is not about money and fame, but rather the fundamental act of cultivating creativity as an everyday devotion. Every time Shane picks up his guitar, he commits a leap of faith that what he does matters in a realm beyond money and glory. It is a beneficent reminder that we all can romance the creative impulse for no other reason than it is essential to be(com)ing human. Whenever one of us takes pen to paper or brush to canvas; moves in ecstasy to rhythms no one else can hear; plants a garden or sings aloud to the skies or a shower stall: We commit a sacrament of communion, we declare “We are here. We matter.”

So what next? First up, Parish is on a two-week tour that is his first troubadour action since COVID shut everything down. And a new Ahleuchatistas album – this one a trio with drummer Dannie Piechocki and bassist Trevor Dunn - is in post-production and scheduled for release later this year on Dunn’s new Riverworm label.

The only safe bet about what to expect next from Shane Parish is the same committed artistic hunger and delight-in-discovery that has been his hallmark since the first Ahleuchatistas album landed in 2003. Check him in person when you can. In the meantime, there is a ton of fun on tap at his Bandcamp page. A thin $9 per month subscription gains you instant access to his entire back catalog.

Go.

Rob Rushin-Knopf blogs about culture at "Immune to Boredom."