Repeatedly Almost Famous

In the late 1960s, a soul band called the Chevelles came together in Milledgeville, Georgia. By the time they graduated high school, they already had a hit record and had performed at Harlem’s legendary Apollo Theater. But they never got their due. Here’s their story.

I made a promise to a friend that I would write this story. It’s not my story, it’s his — his and the friends he grew up with in a little Georgia town. They had a dream and made it come true for a while. They sought a glorious prize and almost had it for a while.

I’ve asked myself repeatedly whether I even have a right to tell this story. But Curtis Davis seemed to think I could, and he asked me to, and I said I would — so here it is.

~~~

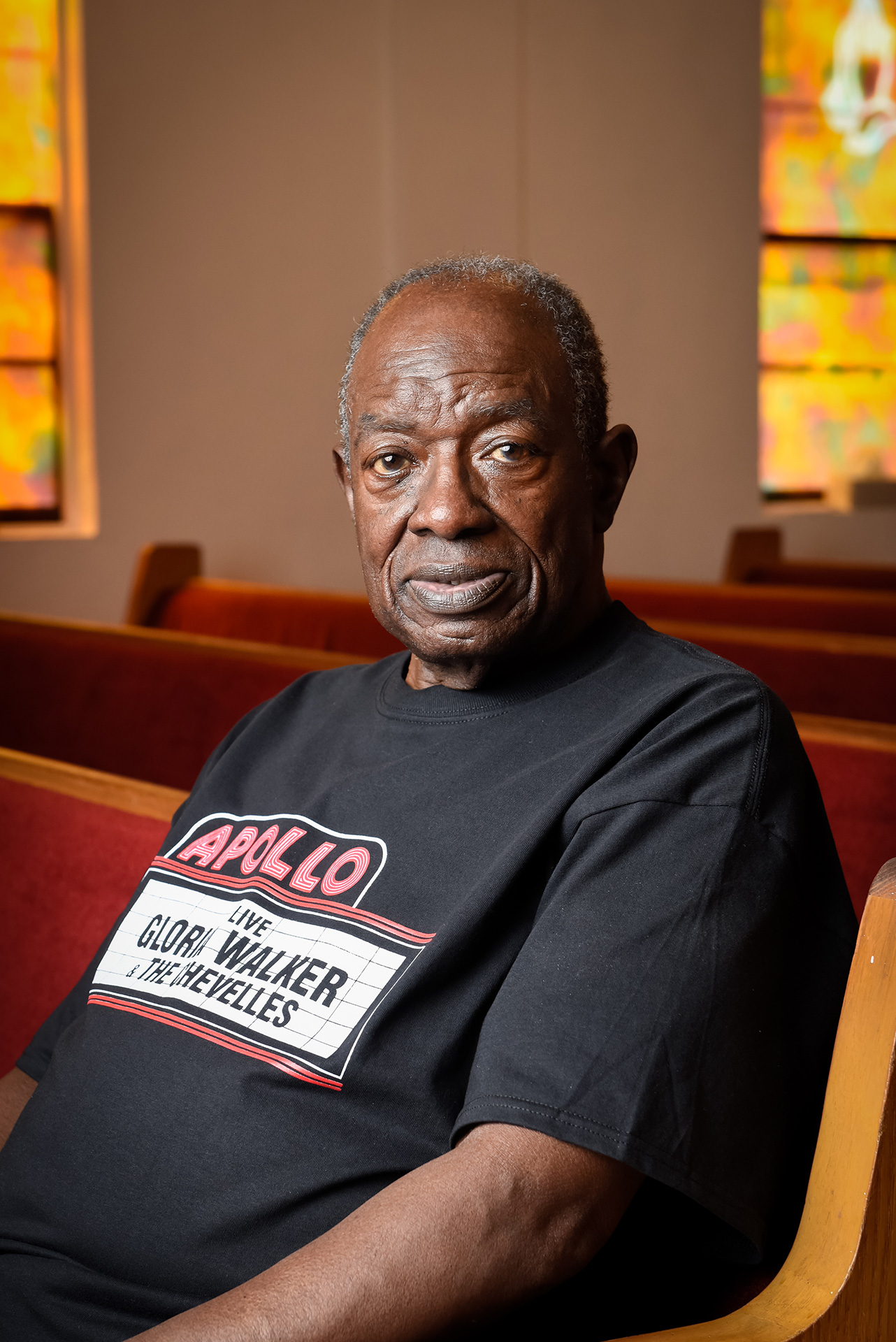

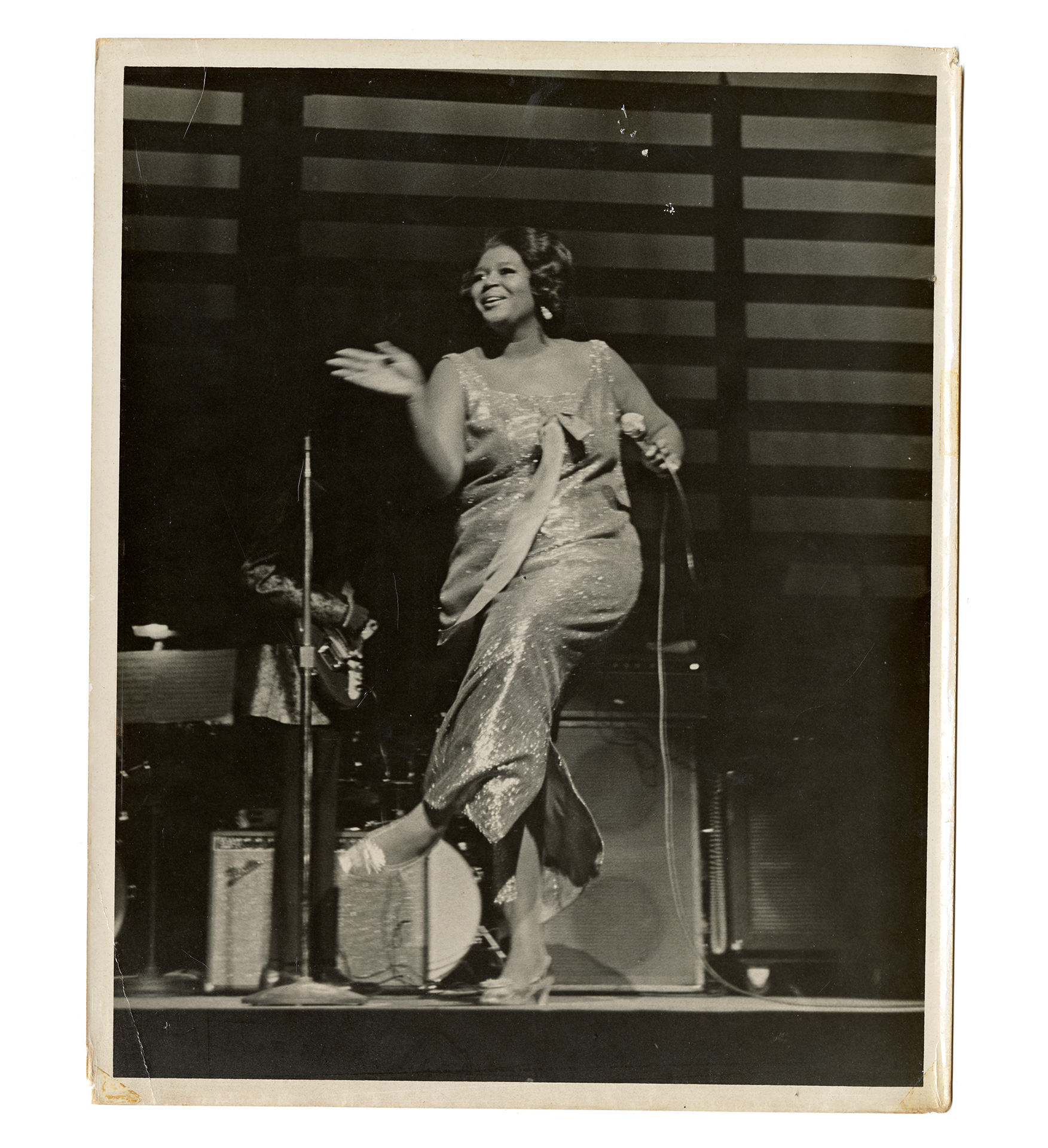

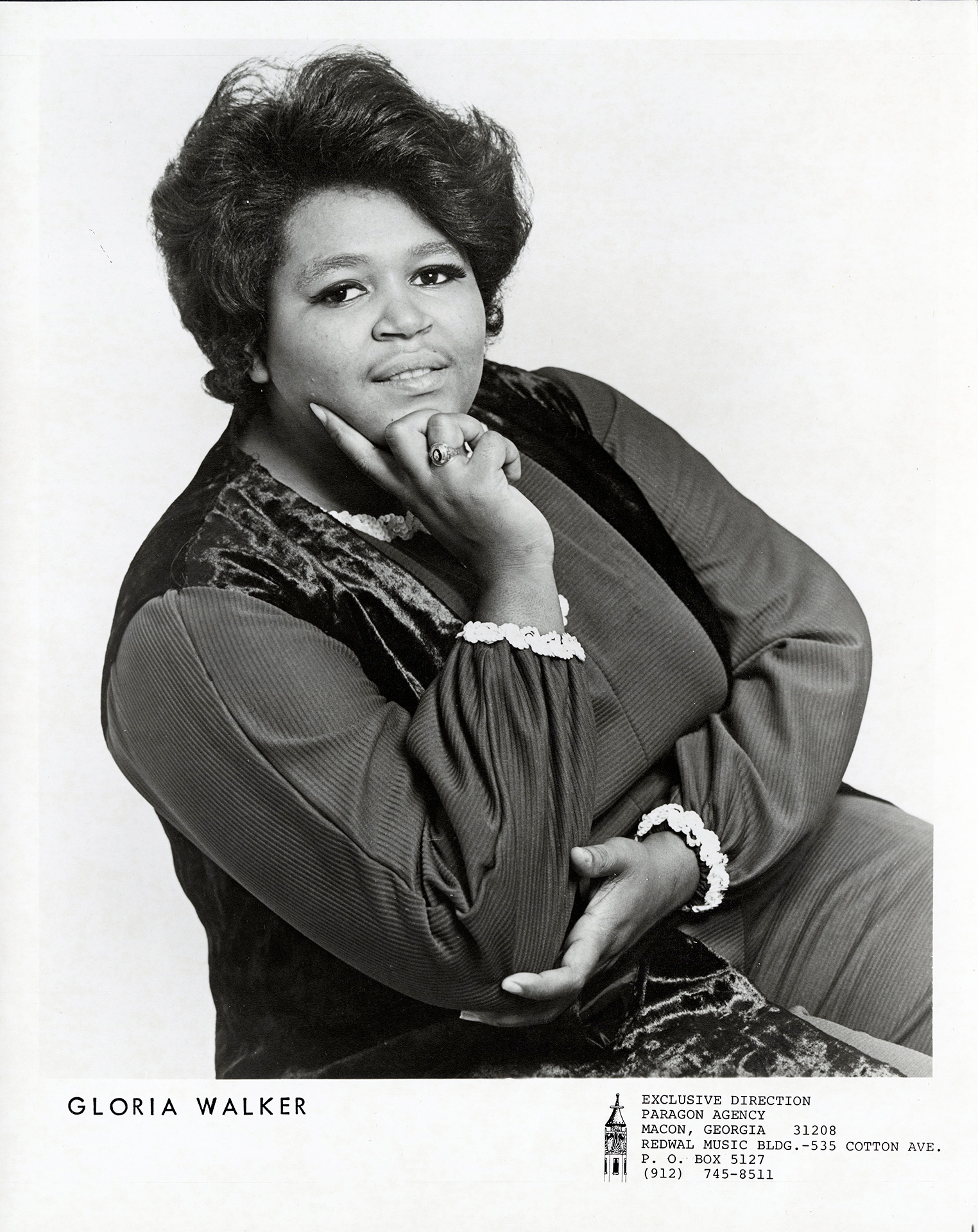

It’s summer 1968, and the Chevelles are on top of the world. They’re working three gigs a night at Detroit music clubs from 4 in the afternoon until 6 in the morning, making only $3 apiece for the overnight entertainment marathon but hell, they’re teenage kids and they’re firing on all cylinders. They’re living on barbecue sandwiches, baloney and soda pop and most of them are sleeping in the basement at the home of Curtis’ uncle, but they are hot, hot, hot. It's the year Marvin Gaye hears it Through the Grapevine, James Brown wakes up in a Cold Sweat and Aretha Franklin has her Chain of Fools. The Chevelles are right there in the soul music mix, adding their own flavor to the stew. Oscar Havior is finding his groove on the cheap TrueTone guitar his uncle bought him at Western Auto, and his brother James “HeyBoy” Havior is in the pocket on the drums. Donzell Reeves has keyboards, laying down the bass line with his left hand. Lonnie West and Emmitt “Red” Green play horns, and out in front is Gloria Walker — magical Gloria with the heartbreak in her voice and the fantastic moves, doing the moonwalk before it even has a name, working her charms on the audience all night long.

“We come from the South, went to Detroit and we took over number one band in Detroit,” West recalled recently, speaking slowly and matter-of-factly, savoring the memory at age 72. “And from then on, the Chevelles was moving. I wouldn’t say well known, but we was moving up.”

Before long, they realized every teenage band’s impossible dream: a hit record getting airplay in Detroit and New York City and an upcoming gig at New York’s legendary Apollo Theater … and then suddenly it was over, like a dream, and they were back in their little hometown of Milledgeville, 30 miles east of Macon, Georgia. It was like they had been nowhere at all. Half of them were about to start classes for their senior year in a segregated high school. These half dozen Black kids had nothing to show for their summer adventures except for the incredible story they could tell. Their manager, on the other hand, had a new Cadillac, likely bought with proceeds from their hit single.

They were almost famous in the summer of ’68 – and that was just the first time. Repeatedly through the years, they became almost famous. They cut records at studios that abruptly went bankrupt before they could market the music. Their singer, Gloria, was wooed by soul stars James Brown and ZZ Hill but she refused to go on the road with them without the Chevelles. During the course of a decade, as they evolved musically through the soul sounds of the ’60s into ’70s funk and later disco, they aimed for the top and had a good shot at it, but somehow each time they got diverted just before the skies opened. They made piles of money for others — the managers, the clubs, the promoters, the record companies — but hardly anything for themselves. It took a while to dawn on them that they were somebody else’s payday.

“We was thinking about girls and wasn’t thinking about no money,” said Oscar Havior, now 70, speaking rapid-fire about their early days. “We didn’t know anything about the business part. … We was young and didn’t have nobody to explain it to us.”

All these years later, some of their music has developed an online cult following, and a previously unreleased album by members of the Chevelles has finally reached the market.

But still, the musicians in Milledgeville wonder if a portion of the proceeds will ever come back to them.

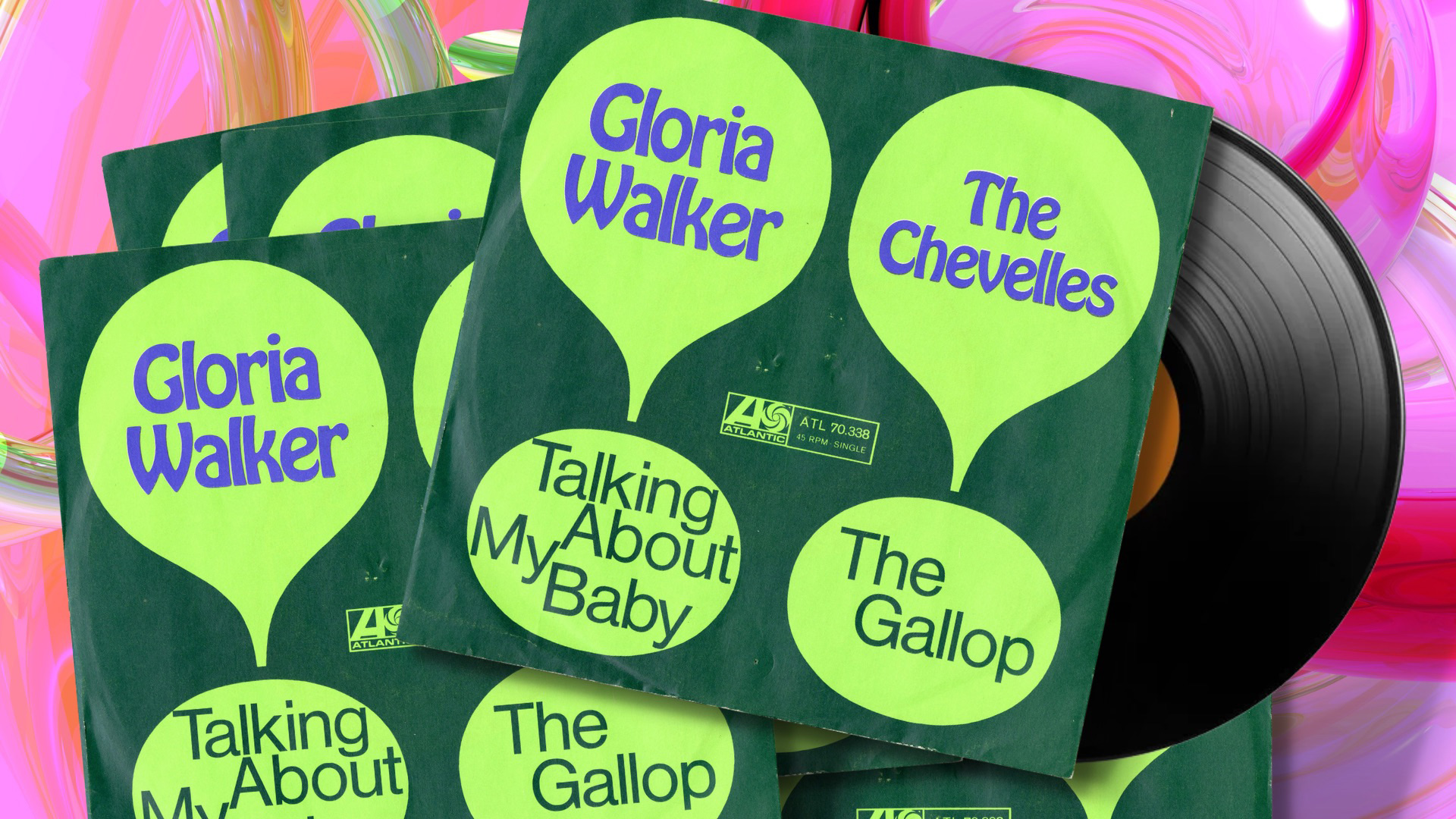

"Talking About My Baby" by Gloria Walker & the Chevelles

~~~

It all started with Curtis Davis, who put the band together even though he was not a musician himself. Curtis’ love affair with music started back in the 1950s with his grandfather, Simon Davis.

“How I got into music, first of all, my granddaddy, he was a blind man and he played guitar. And he played downtown,” Curtis said last year in an oral history videotape recorded by Georgia College librarian and researcher Evan Leavitt. Curtis said his grandfather played on the sidewalk in Milledgeville, outside McCoy’s hot dog shop.

“His friend that played with him played rub-board. You know what you scrub clothes with? That was his drum. His tambourine was on top of the rub-board.”

Blind, Black guitar players occupy an almost mythical place in the lingering memory of the Jim Crow South. Before they gained a few measures of fame, figures such as Texas’ Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willie Johnson, Florida’s Blind Blake, South Carolina’s Blind Rev. Gary Davis, and Georgia’s Blind Willie McTell all lived on spare change at the mercy of the streets while putting down the deepest roots of American music.

Curtis Davis talks about his grandfather

But Curtis’ grandfather, Simon Davis, lived and died in obscurity, never finding any fame at all. Only a few old-timers, who heard him play 60-plus years ago outside McCoy’s, remember him today.

“It was mostly church music,” recalled his granddaughter, Betty Davis Williams. “They sang on the street, back in the day. My mom and her sister and Simon Davis — and (a man) they called Popcorn, who had the rub-board.”

Simon Davis never made a recording, she said. His great-granddaughter, Kaori Williams, said no one in the family even has a photograph of him.

But he left an indelible impression on his grandson Curtis, who grew up in the same household as his cousin Betty.

“I was young then, but I told him when I grow up, I want to be just like my granddaddy because I had a lot of respect for him,” Curtis remembered.

In a sense, Blind Simon Davis is the reason the Chevelles came into being – the Chevelles and a parade of other bands that coalesced around Curtis Davis through the decades. A host of musicians became part of Curtis’ musical dreams as time went by, and as it happens, one of those musicians was me. I share their link, through Curtis, with Blind Simon Davis.

~~~

Curtis Davis was my friend. About two decades after the demise of the Chevelles, he formed a gospel quartet, and in 2004 he asked me to play guitar for them. I was living in Milledgeville then, working for the local newspaper, and for several years I played with his group the Emoni Gospel Singers at music programs all over central and southern Georgia. From time to time, Curtis would mention that he had once had a band called the Chevelles.

"I was young then, but I told him when I grow up, I want to be just like my granddaddy because I had a lot of respect for him."

“An R&B band?” I asked him. He said yeah. I imagined that maybe they were a local band, like all the local gospel bands Emoni performed with. Maybe they played at some of the clubs around Milledgeville, Sparta, Eatonton and Macon. In my imagination, they got no further. I should have asked him more about it. Having worked my entire adult life as a journalist, it would have been a natural thing to do. But for me, part of playing with Emoni meant not acting like a journalist, not trading on other people’s stories – just flowing with the music and the musicians, soaking in the experience. So I left it there. Even when Curtis mentioned later that they’d played at the Apollo and made some records and never got paid much for it, I didn’t think to ask more.

A few years later, my wife and I moved to Atlanta, so I didn’t see Curtis as much. We kept in touch by phone, and I came back to play at some of Emoni’s special anniversary shows. But I forgot all about the Chevelles.

Then last fall, Curtis called me.

“Don, I need you to write about the Chevelles,” he said.

“What, like for the Milledgeville newspaper?”

No, he said, something that would get people’s attention all over the country. It made no sense to me, but what did I know? I had completely missed the point this whole time.

~~~

Curtis didn’t know much about music, but he knew about working with people, and he didn’t fear hard work. When other kids were just hanging out and having fun during summer vacations, Curtis and his brother were cutting grass with a lawnmower their mother bought for them, and they purchased their own school clothes with the proceeds. On the Boddie High School football team, he was known as “Goose,” for his speed and elusiveness. And despite his lack of musical chops, he learned a few things about bands. He said he used to sneak out of his family’s home at night and go to the Ebony Lounge, out east of town, where some of the big-name soul groups performed when they came through Milledgeville on the Chitlin’ Circuit. At age 16, he said, he took notes on a band called the Tornadoes.

“I’d slip out the window at my house around 12, 1 o’clock at night,” he said. “I done it two or three times, but the third time my mama caught me. When I come back inside through the windows, she hit me on the back of my head with a broomstick. But I had to go see those Tornadoes. I really got my inspiration from them.”

In 1967, freshly graduated from high school, he began to pick his band: Donzell Reeves on keyboards; the Havior brothers, Oscar on guitar and James, nicknamed HeyBoy, on drums; Emmitt “Red” Green on saxophone; and Lonnie West also on sax. Though he couldn’t play a horn, piano or guitar, Curtis filled out the band’s rhythm on the conga drums. Julian “Butch” Edwards played sax with them part-time and later on, Henry “Boot” Mitchell joined them on trumpet. Only Curtis and Donzell had graduated; the rest were still in high school. They knew music from playing in the high school band and from growing up surrounded by church choirs and gospel quartets. Convinced that they needed a female lead singer to front the group, Curtis polled the others. Their choice: Gloria Walker, a senior at Boddie High and a vocalist of some renown among her friends. Raised without her mother, who had moved up north to Cleveland, Ohio, and virtually estranged from her own father, a local taxi driver, she carried a load of pain that she poured all into her songs. The band became her family.

The band also needed to find a name. In 1967, Curtis’ family bought a shiny blue Chevelle automobile. Blending the words Chevrolet and gazelle, the Chevelle held a prime place in the growing market for muscle cars. A Chevelle was an object of pride in a working-class Black family in Milledgeville, Georgia’s antebellum capital city, home to the state’s largest public mental hospital and still largely segregated in the mid-1960s. That family might not have much, but a late-model car like the Chevelle could be a mark of prestige, even parked outside a modest house in a part of town where Black folks lived and white folks didn’t.

It dawned on the teens that their new cars should give them a name: They became the Chevelles.

“I’d slip out the window at my house around 12, 1 o’clock at night. I done it two or three times, but the third time my mama caught me. When I come back inside through the windows, she hit me on the back of my head with a broomstick."

For a year, every day after school, they rehearsed in Curtis’ family’s front yard in West End, driving the neighbors crazy with the noise and figuring out for themselves how to make the sounds that were rocking their world.

“Our first gig with the Chevelles, I think we played at the American Legion here in Milledgeville,” West said. “And to be honest with you, after practicing a whole year, we messed up the show. So we canceled all our engagements and went back into rehearsal. It was, if we go out back out there, we gonna do it right or don’t do it at all. So we went back the second time, played a dance, and it went beautiful. And that’s when the Chevelles band took off.”

By the summer of ’68, they were rocking steady, drawing crowds from Milledgeville and the little country towns nearby. And around that time, Curtis’ uncle Eugene came back to town from Detroit, where he had moved some years earlier. He claimed to have connections in the music business, and he liked what he was hearing from the Chevelles. He was also, Curtis thought, a solution to a growing problem: how to manage the Chevelles’ burgeoning success.

“It got so heavy for me, I couldn’t handle it,” Curtis said. His uncle seemed like an ideal manager.

Uncle Eugene “got back to Detroit and called Curtis and told him he had booked 33 dances in Detroit for us to come up and play,” West said. “So OK, we got our money together to buy those tickets to Detroit.”

They had to chip in and pay for Gloria’s bus ticket, because her father didn’t approve of the trip and wouldn’t buy her one. The band, her improvised family, came through for her.

But in Detroit they got an unpleasant surprise.

“We get to Detroit and Eugene Davis didn’t have not one dance — not one,” West said. It had just been a ploy to draw them. “We had to go play for a club, free, because they didn’t know exactly how we’d sound, to get booked in there.”

Nevertheless, they did it – and they made the cut, he said.

“We played three gigs a night. First one started at 4 o’clock. Played at one lounge from 4 to 8. Left there and go to another lounge and play there from 10 to 2. Leave there and go to a coffee house and play there from 3 to 6. Then we got paid $3 apiece for those three gigs, just three bucks.”

It was just enough cash to buy a barbecue rib sandwich, plus 50 cents worth of baloney, cinnamon rolls and strawberry soda for breakfast.

“It really was terrible, but it was enjoyable too …. Gloria slept upstairs with Eugene Davis’ daughter in the bed. Gloria was the only female. The rest of the band members, we stayed in the basement sleeping on mattresses on the floor,” West recalled. “But like I said, we were a band, we were together. We just about didn’t care where we stayed at.”

Although Uncle Eugene had failed to find gigs for the band, he did come through on a recording deal. The Chevelles went to Magic City studio in Detroit where they cut “Talking About My Baby,” a song they had honed during the summer of all-night shows. It was mostly just a long rap by Gloria, telling about a boy who sweet-talked her but left her for another girl. In the club, her rap served as an intro to the band’s cover of “I’d Rather Go Blind,” which Etta James had made into a hit one year earlier. On the Chevelles’ recording, the rap fills up virtually the entire track, with the band playing behind her. It fades out just as she’s launching into James’ song: “Something told me it was over …” For the flip side they improvised “The Gallop,” an instrumental loosely based on “The Horse,” by Cliff Nobles, a boogity dance tune that carried a hint of what would eventually evolve into disco.

So they had conquered Detroit and made a record, but the band was getting tired of having nothing else to show for it but barbecue and baloney.

As Curtis recalled, “I thought I was going to get somebody that was going to take care of us, but didn’t. That’s what happens when you get your kinfolks sometimes. They don’t do you like they supposed to be doing. They look out for themselves. So I have to admit it that my uncle did us wrong, really – but I guess that’s one of the lessons we had to go through.”

West said, “(Eugene Davis) was raising sand with us ’cause we were eating the groceries, but he was buying it with our money. It kinda got us in a difficulty … so we had to confront him. And he was a big guy. Everybody was just about scared of him because they said he used to be a prize fighter or whatever. But we had to do something to confront him, so we did.”

That ruptured things. The Chevelles left Detroit and took the bus back home.

And then the unexpected happened.

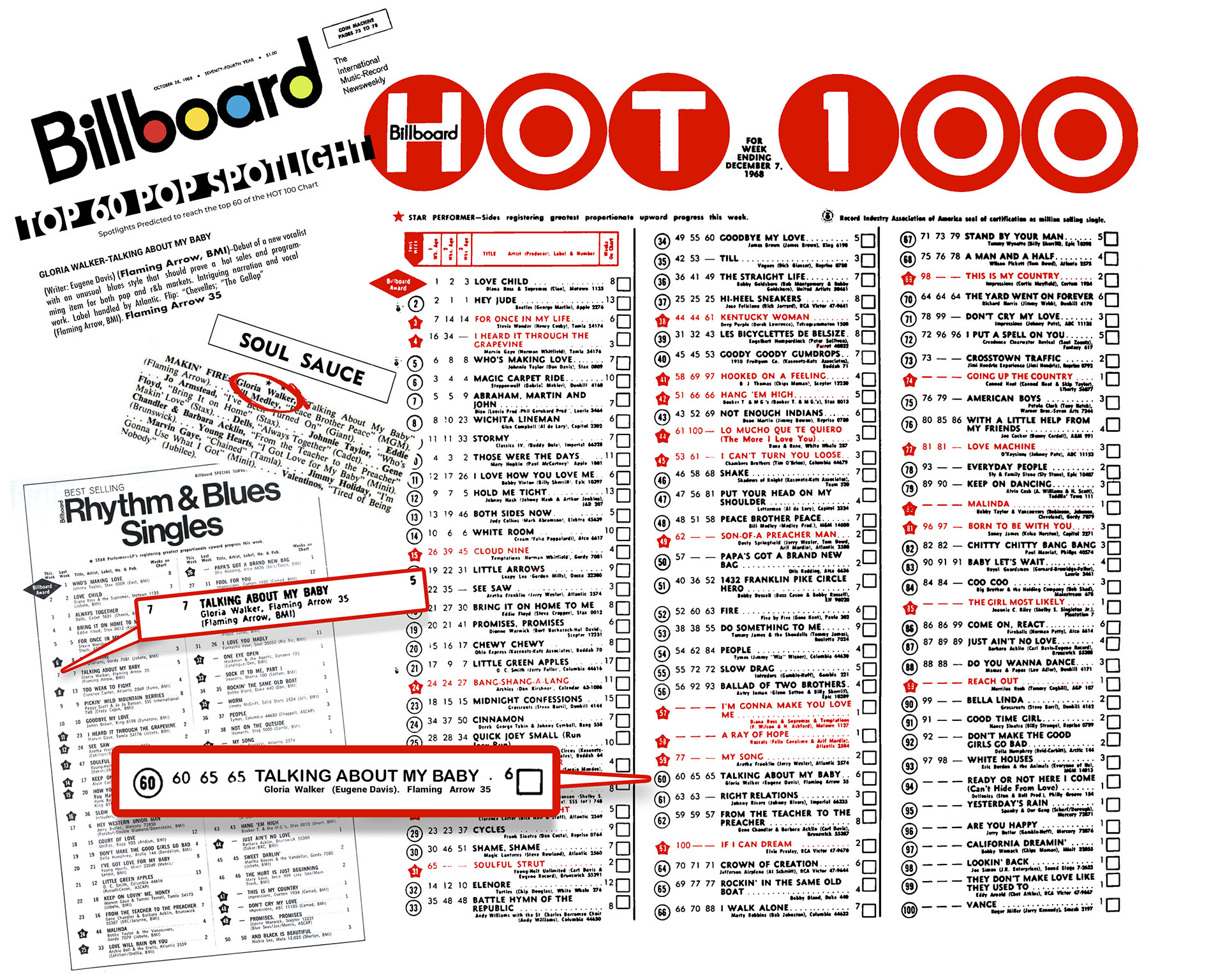

“Talking About My Baby” hit the charts.

“It just took off. It got on the chart pretty quickly and started going up the chart,” said Georgia College’s Leavitt, who has done deep research on the band.

Released in October, the song hit Number 7 on the R&B charts by early November, and No. 60 on the Hot 100. It was getting strong airplay in Detroit and New York City.

“For that brief moment, they were famous,” Leavitt said. “And Gloria’s name was getting put right next to Aretha Franklin when people were talking about the music that was out there at that moment. It had a buzz about it.”

Eugene Davis had done another thing right: He had forged a deal with Atlantic Records to distribute “Talking About My Baby,” which carried the label of his own Detroit-based Flaming Arrow Records. They had a hit record, and it was being marketed by a music industry powerhouse. Success seemed to be on their doorstep.

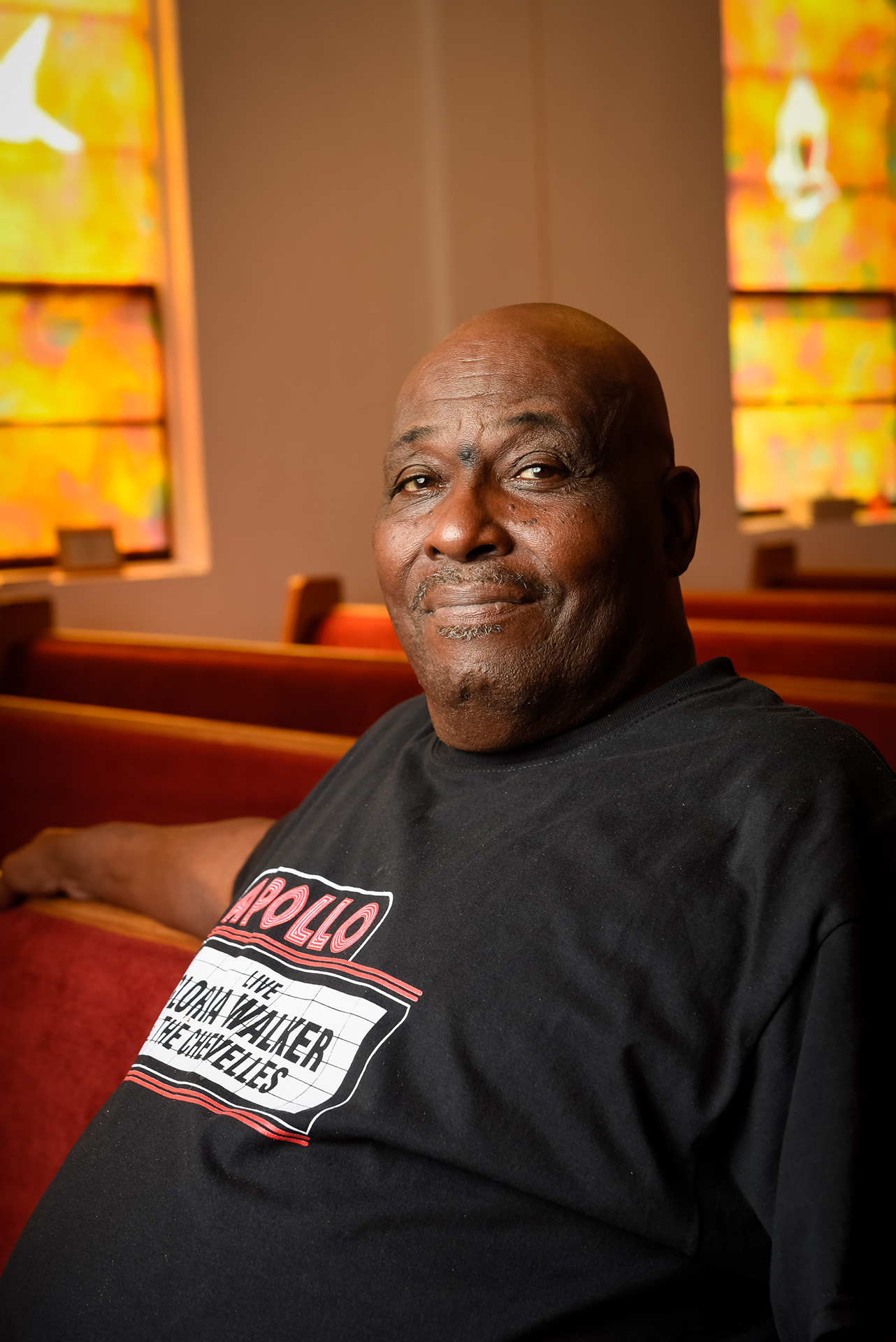

Gloria Walker was invited to perform at The Apollo Theatre in Harlem. But the Apollo didn’t want the whole band — just Gloria. Despite that, three others flew up there with her on Atlantic’s dime: Eugene Davis, who had put the deal together, band organizer Curtis Davis and guitarist Oscar Havior, who could show the Apollo musicians how to do Gloria’s tunes.

“I really didn’t know what the Apollo was,” Havior said. “It was just like, I’m going somewhere to play. Now I know.” But back then, he said, “I didn’t realize what we were really doing.”

He got special permission to take a few days off from school, and one of his teachers warned him to be careful and “don’t talk to nobody” in New York City. For the country boy, “I was in a whole different world, man. I ain’t never seen that many folks in my whole life,” Havior said. They stayed at the Henry Hudson Hotel, watched rehearsals for “The Ed Sullivan Show” during the daytime and played two shows a night for five nights at the Apollo.

“When I played there, I didn’t see nobody ’cause of the lights,” Havior said. “I knew people was out there, but ... the lights were so bright. They had a big old band and I was playing the guitar. I know I was out of tune, but they played along with me, made me sound good.”

And Gloria knocked the New York audience out.

Curtis Davis talks about the Apollo Theater show

“Man, lemme tell you something. She put ’em to shame,” Curtis said. Laughing, he added, “They got mad at her. Gloria went up there and showed out. … When Gloria left there, they knew who Gloria Walker was.”

And when they got back to Milledgeville, they were famous — at least among everyone who was young and Black. They had a hit record. They had made it big in New York and Detroit. Their performances were drawing crowds in Milledgeville, Macon and all across central Georgia.

“Now, when I think about it, we was famous and didn’t know it,” Oscar Havior said. “Just didn’t get the money.”

They also had to finish school and some of them had to work. Lonnie got drafted and was sent to Vietnam. To fill in the gap, Henry “Boot” Mitchell joined the band on trumpet, but it all kind of dwindled out, at least as far as Gloria Walker and the Chevelles were concerned. Somehow the pieces no longer fit together. Eugene Davis’ deal with Atlantic came apart. Maybe it was because he was now estranged from the Chevelles, or because established artist Etta James wasn’t happy to see some hick band make a hit record off her own song. And there were frictions within the group itself. Gloria and HeyBoy had gotten married and there may have been some jealousy among the band members. When asked, the surviving members are vague about it, and Leavitt says he hasn’t been able to determine exactly what happened. But just as quickly as the Chevelles had rocketed upward, they fell back to earth. The young ones finished out their senior year in high school and the older ones re-entered the routine of their jobs, mostly at the state hospital.

Offers kept coming, with promises of fame and good times, but they were only for Gloria. James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, asked her to come on the road with him – twice.

“She called me and told me she had an interview with James Brown, and she wanted me to go with her,” said her childhood friend Gloria Jean Davis. Emmitt Green drove the two Glorias 90 miles to Augusta in his Chevelle.

Gloria Jean and Emmitt had to wait in the car while Gloria Walker went in to talk with Brown at his radio station. She was in there about two hours.

“When she came out, she was excited about it,” Gloria Jean said. “She told us, ‘He wants to put me on the road.’” But she had told Brown she had to think it over.

A few months later, Brown summoned her again, this time to meet him at the Key Club in Macon. And this time Gloria Jean went inside with her. She recalls being awestruck meeting Brown, but Gloria Walker took it in stride.

“He told her I just want to put you out there,” Gloria Jean recalled.

Gloria Walker replied, “If I go can I take my band?”

“And he told her, ‘No, you don’t need a band. I got everything.’ And she finally told him she couldn’t do it. She wanted to take her band.”

Gloria Walker had turned down James Brown – twice. She wouldn’t go without her musical family.

They drove back home from Macon, crushed.

“She really wanted her band to go,” Gloria Jean said. “We all was young. And they was like family to her, and she actually wanted them to be with her wherever she went.”

Other offers came from Southern soul artists ZZ Hill and Johnny Taylor, but for Gloria, leaving her band behind was a dealbreaker. She took none of the offers.

“Gloria went to getting deals from everywhere, but she never did (go),” Curtis said. “Gloria, she always kept us in mind. They tried to steal her away from us, but she never did. She stayed with her group.”

~~~

Yet the music bug never quit biting. Over the next decade, the members of the Chevelles kept on playing when they could, balancing their band time with their day jobs. With some additions and subtractions, the core musicians mostly stayed together – becoming in turn the Mighty Chevelles and later the Music Makers. As The Mighty Chevelles, they gravitated into funk, recording an album called “Black Gold” at an Atlanta studio. Later, as the Music Makers, they recorded at Capricorn in Macon and TK Records in Miami. But each of those studios was on its last legs by the time the band arrived, and a couple of the recording companies folded before the music could be properly marketed.

Some of the Chevelles went on to play with big-name singers. After returning from Vietnam, West made music with Bobby Marchan, Teddy Pendergrass, Patti LaBelle and James Brown, and he toured for four years with Al Green. Emmitt Green toured with Clarence Carter. When soul artists like Carter, Percy Sledge and William Bell came through Georgia, the Chevelles members often backed them up as a pickup band.

Gloria became one of central Georgia’s first female DJs, going by the moniker “Disco Lady,” a phrase made famous by Johnny Taylor’s hit song. She recorded a few more singles on her own, but they went nowhere. Eventually, Gloria and HeyBoy divorced, and she moved to Cleveland, where her mother had gone when Gloria was just a child. While there, she began to drink and she couldn’t stop. When she returned to Milledgeville years later, she was a sadly diminished woman.

“When she first moved back here, she called me and stayed with me,” Gloria Jean said. “That’s when I found out that part of her life wasn’t really good, because she had developed a drinking problem. I think it came from all those years of disappointment on top of disappointment. It really was sad.”

Suffering from diabetes and the years of drink, Gloria Walker died in 2005 after a dialysis session in Macon.

~~~

When Curtis told me I had to write this story, he told me to call Evan Leavitt at Georgia College.

It turned out that, unlike me, Leavitt had asked all the right questions.

He had heard about the Mighty Chevelles a year earlier when a local community organizer named Greg Barnes dropped by to discuss working with the college on an exhibit to recognize Milledgeville’s musical heritage. He had a copy of the Mighty Chevelles’ album, “Black Gold.”

"I’m a music lover and I love soul music and R&B and funk and gospel and all that, and to see him sitting there with this record and him saying this is from Milledgeville, it blew me away, because I’d never heard of them.”

“He sat down with this record and said, ‘This is a Milledgeville band,” Leavitt recalled. “And I said what are you talking about? Because I’m a music lover and I love soul music and R&B and funk and gospel and all that, and to see him sitting there with this record and him saying this is from Milledgeville, it blew me away, because I’d never heard of them.”

So Leavitt began to study the whole evolution of the Chevelles, the Mighty Chevelles and the Music Makers. He sat down with all the surviving members and made the oral-history videotapes that much of this article is based on. He put together a commemorative book on the Chevelles and Gloria Walker, which he presented to the surviving members and their children. He’s curating a multimedia exhibit which he expects to open at the college library’s fledgling museum in September.

And he told me that the Chevelles and their related groups have developed a cult following online and among record collectors.

“An original ‘Black Gold’ is easily $500 to $1,500, depending on the condition,” he said. Last year, a vintage 45 rpm single with the Chevelles backing up a singer named Joseph Webster on a tune called “My Love is So Strong” made someone a small fortune.

“In the soul circle of that world of collecting, it’s considered like the gold standard of Deep Soul,” Leavitt said. “It sold late last year for $15,000.”

Once again, the Chevelles were someone else’s payday.

But meanwhile, another thread wove itself into the story from a completely unexpected direction.

A couple of years ago, an old man in Macon pulled some reel-to-reel tape out of a linen closet where it had sat for nearly four decades. Ernest Hill, better known to friends and associates as Bruh Hill, began his career as a construction contractor but he dabbled in music management and promotion. He began managing the Chevelles in the late 1970s, changing their name to the Music Makers in order to better separate them from their previous manager and contracts. He took them to Capricorn’s studio in Macon to record an album and later sent them to record at disco powerhouse TK Records in Miami.

But Capricorn was in decline at the time, and so was TK Records. Both companies went under before the Music Makers material could be properly marketed. The band’s Capricorn material was never released at all. So Hill, who had paid for all the recording sessions, took the master tapes home and put them away. No one but Hill even knew he had them.

“I took ’em down to Capricorn and recorded in 1979, and I had (the tapes) ever since in my closet at home,” Hill said. “And one day I said, ‘Hey, I’m gon’ leave this world and leave all that stuff there.’” Not liking the idea of unfinished business, he said, “I decided to pull it out.”

He reached out to music industry connections he still had in Chicago. Was anyone interested in the Music Makers’ unreleased tape?

He was soon steered to Now-Again Records, a Los Angeles-based company that specializes in resurrecting old recordings of funk, soul, and psychedelic rock from the 1960s through the 1980s. They made a deal.

And last year, after remastering and reengineering the old tapes, Now-Again released the Music Makers’ recording under the title, “You Can Be.” Included with the album was a booklet with extensive history on the band written by Brian Poust, a longtime record collector and researcher of funk and soul music.

Poust had known about the Chevelles and the Mighty Chevelles for years, and had even met and interviewed the band members. But not until Now-Again Records was putting together the band’s long-delayed album did he realize that they were also the Music Makers.

He said the band’s near-misses with fame represent a common refrain in an unforgiving musical environment where many strive but few succeed.

“The Chevelles recorded more prolifically than a lot of local-type musicians did, but … their failure to produce more hits isn’t on them, I don’t think,” he said. “Their story is familiar in that way. There’s a lot of really good artists, good musicians and songwriters that things just didn’t fall their way for any multitude of reasons.”

Hill, now 81, says he had ownership of the Capricorn master tape when he made his deal with Now-Again, but he also said he feels some obligation to the musicians who recorded the songs.

“They waiting on me,” he said. “Some of them done passed, but they got a family. I ain’t gon’ walk off and leave ’em. They gone, but they were part of that album. If that money come through my hands, I’m gon’ make sure their family get it.

“You might have never met nobody like me, but that’s the kind of man I am.”

Curtis said that as time went by, he had prayed for something like the Now-Again deal.

“I said, ‘Lord help us to get compensated for what we did in the past.’ When you’re sick, you start thinking about things you wouldn’t normally think about. I started thinking about all the things I did in my past, all the things I accomplished in my past. I said, ‘I did a powerful thing.’ And when I was in the hospital — you know I had three heart attacks, heart bypass, stroke. … After all that, He still let me stay here to see this day.”

Sort of.

~~~

Curtis wasn’t among those who were part of Hill’s deal with Now-Again, but some of the band members were. I don’t know all the ins and outs of that, and I’m sure each of the parties has their own story. And separately, Gloria Walker’s niece Edona Adams says she and Curtis made a deal with Now-Again to be part of any future arrangement to re-release the band’s material with Gloria Walker.

Now-Again founder Eothen Alapatt told me he loved the Music Makers material when Hill brought it to him. He got a producer friend, Kenny Dope, to remix the original tapes.

“It was just an intense set of work,” he said.

Meanwhile, a friend put him in touch with Curtis. They talked about how they could also re-release the Chevelles-Gloria Walker recordings.

“There were some questions as to who might or might not have the rights to the Chevelles,” Alapatt said. “Curtis and I got on the phone and we had a series of intense conversations. In one of them he was actually in tears. It was really powerful: He was talking in the way we do in private … about just how difficult it was to make this music and to hold onto hope and to maintain hope that somehow this music would be discovered.

“Here I was putting out this record with his manager who had against all great odds saved those tapes. He was pretty thrilled. I mean, he had questions about the business, as he should. And we had a lot of things to iron out, in terms of people who might have done this deal or that – but ultimately, he was just thrilled that something was going to happen.”

The album release by itself hasn’t generated much revenue, Alapatt said, but Now-Again is also trying to make money through “sync licensing” — placing particular Music Makers tunes in TV shows, movies and commercials.

“At this point it’d be nice to make everyone some money. I know Ernest Hill, the manager, is keenly interested in making some money off of this.”

So it seems that one way or another, after all this time, some kind of payday might be coming for the musicians who made up the Chevelles and its offspring.

That’s why Curtis was calling me last fall, to write something that might help make that payday happen.

~~~

When I went back to Milledgeville to talk with Curtis and Evan, I began to understand, finally, what Curtis had been trying to tell me. Curtis was by now part of what had become a kind of extended Chevelles community, which encompassed the surviving band members and the relatives of those who had passed away. Among them was Gloria Walker’s niece, Edona. A buoyant, energetic woman who runs her own cleaning company, Edona was raised by her aunt and has become the sparkplug and axis of the latter-day Chevelles revival effort. She organizes regular meetings to talk about the group, coordinates with Leavitt on the Georgia College exhibit, talks with Now-Again Records and is planning a Chevelles banquet later this summer.

Curtis took me to meet her at a motel where she and business partner Barbara Evans were doing a cleaning job. He told Edona that I was going to write an article about the band. It made me uneasy because I wasn’t at all certain I wanted to do it or even could do it. I’m retired after four decades in journalism and I like not working. Plus, I’ve fallen out of contact with most of the people I knew at magazines where I’ve written in the past.

But Edona listened to Curtis and then she laid a prophecy on me.

“I believe God is going to open the door for you to write an article,” she proclaimed, looking me dead in the eye. “He’s going to do it.”

I told her I’d pray about it, which I meant, but it’s also the polite thing to say after you’ve been hit with a prophecy. And there I thought we’d leave it.

But the very next day — I mean the next day — I got an email from Chuck Reece, for whom I’d written in the past. And his email, which went out to all his contacts, said he was starting a new magazine called Salvation South, and would we like to support him?

It was clearly a sign. At least I took it that way. I emailed Chuck and he said, yeah, the Chevelles sounded interesting and he’d like to publish a piece about them. Now all I had to do was tell Curtis that the article he asked for was really going to happen. Despite my doubts — really in spite of my own intentions — I’d be doing an article on his band. I’ll call him tomorrow, I thought.

And then Curtis died.

The morning of the day I planned to call him, friends in Milledgeville began to post online that he had passed. Sick for a long time with high blood pressure and related health problems, Curtis died in his sleep on December 7, Pearl Harbor Day. He was 76. I had waited too long. It was another narrow miss in a history of narrow misses surrounding the Chevelles. He’s buried in a little cemetery nestled in the piney countryside not far from Sparta. At his graveside memorial, the Chevelles were among the friends and family who spoke up to honor him.

After Curtis died, the heart went out of me for a while. For a couple of months, I couldn’t even bear to think about writing an article. But feeling obligated by Curtis’ request, eventually I began putting it together. And here it is.

I don’t know if the Chevelles will ever see their payday. I’ve done what I could to honor Curtis’ last request of me — and I hope the payday comes.

Sad but well written story of history I never knew. Thank you for bringing it out for all to see.