The Big Bang of Jazz

The pianist James Reese Europe, born in Alabama in 1881, played "jazz" before the world even knew the word. Texas pianist Jason Moran is resurrecting his story.

James Reese Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama, on February 22, 1881. Though his work largely predated the word “jazz,” his importance in the creation and spread of America’s classical music was massive and, like so much of our essential history, not well remembered. Jason Moran is on a mission to change that.

The Texas-born Moran, who is among the finest pianists in the world in any genre, wears many hats. Aside from the 17 albums under his name since 1999 — and dozens of appearances with nearly every prominent musician of the past 25 years — he has written nine movie soundtracks, including director Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” and “13th.” Moran wrote the score for the 2018 HBO documentary based on journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2015 National Book Award-winning exploration of America’s racial history, “Between the World and Me.” He’s been a member of the New England Conservatory of Music faculty since 2010, serves as honorary faculty at several other prominent institutions here and in Europe, and is the Artistic Director for Jazz at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

Moran is also a walking repository for the history of piano in jazz. He’s literally got that world in his hands, and has taken great strides (sorry, I couldn’t resist) to revive the music of historic greats like Fats Waller.

On January 1, Moran released “From the Dancehall to the Battlefield,” an album that turns a long overdue spotlight on the greatly underappreciated James Reese Europe, a man whose work Moran refers to as “the Big Bang of Jazz.”

In 1891, Europe’s parents, anticipating the Great Migration by a couple of decades, relocated the family from Mobile to Washington, where Europe received intensive musical training. In 1904, he moved to New York.

Then, he hauled off and changed the world.

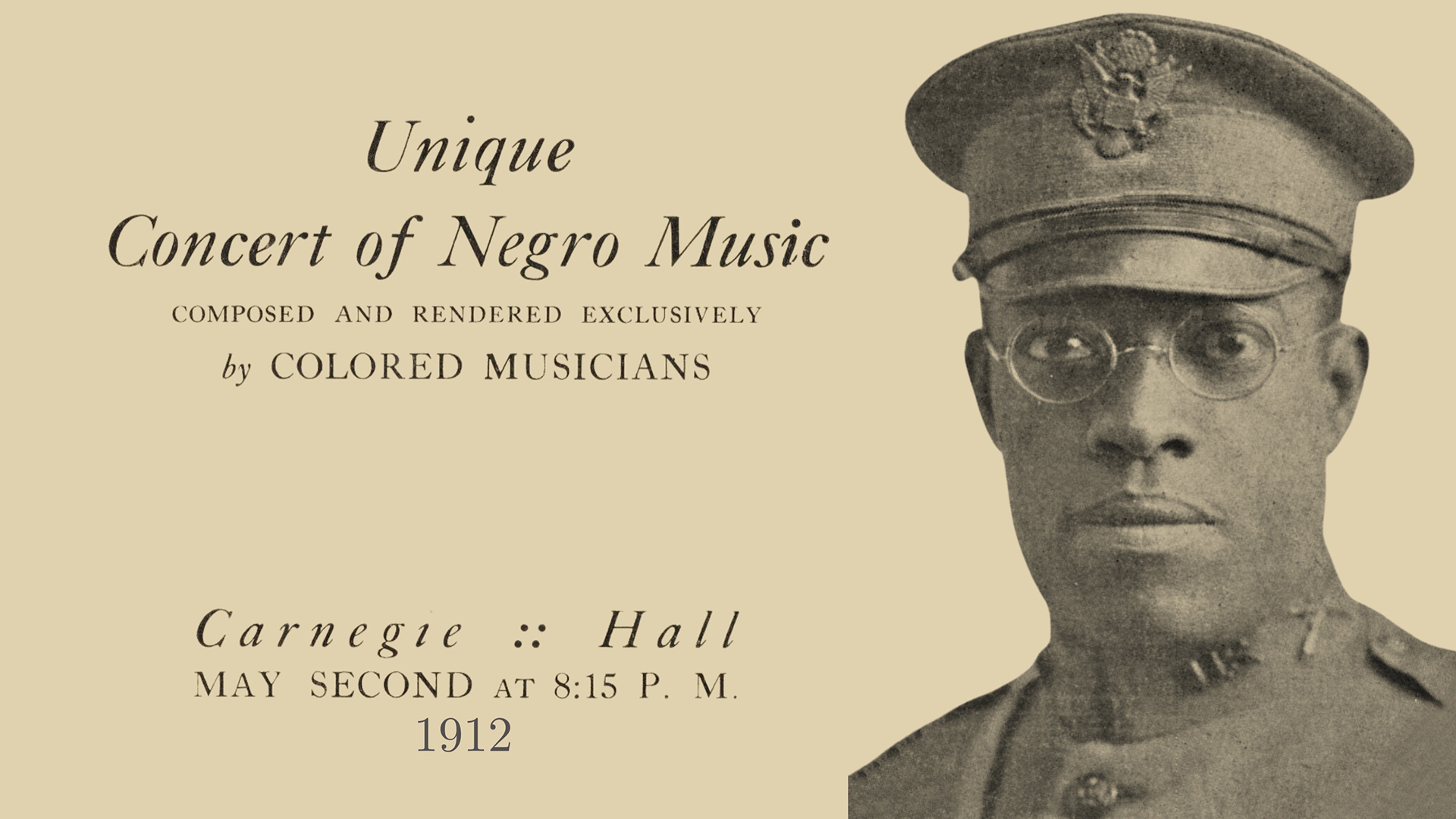

In 1910, Europe co-founded the Clef Club, the first African American musicians’ union in New York. There, he established the Clef Club Orchestra, a 100-member ensemble that in 1912 became the first Black orchestra to play Carnegie Hall, beating the more widely remembered Carnegie “jazz” concerts by Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin by a dozen years and Benny Goodman by over two decades.

Europe’s band was refused participation in the New York National Guard’s farewell parade down Fifth Avenue. An officer told Europe, “Black is not one of the colors of the rainbow.”

Europe’s next band, the Exclusive Society Orchestra, was an in-demand group that rode the ragtime/dance party wave popular with the upper crust. They were also the first African American act signed to a major record label. Then the hugely popular (white) husband-wife dance team Vernon and Irene Castle heard Europe’s band, and they hired them on the spot.

The Castles were huge stars, best remembered as popularizers of the foxtrot, a dance that emerged when Europe offered his arrangement of W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues.” Here's Moran’s take on this Handy classic.

To their credit, the Castles always acknowledged Europe as the innovator, though history often credits them with “inventing” the dance. And when the Castles took Europe and band to London, union rules would not allow “coloreds” in the orchestra pit. Undeterred, the Castles had the band perform alongside them onstage.

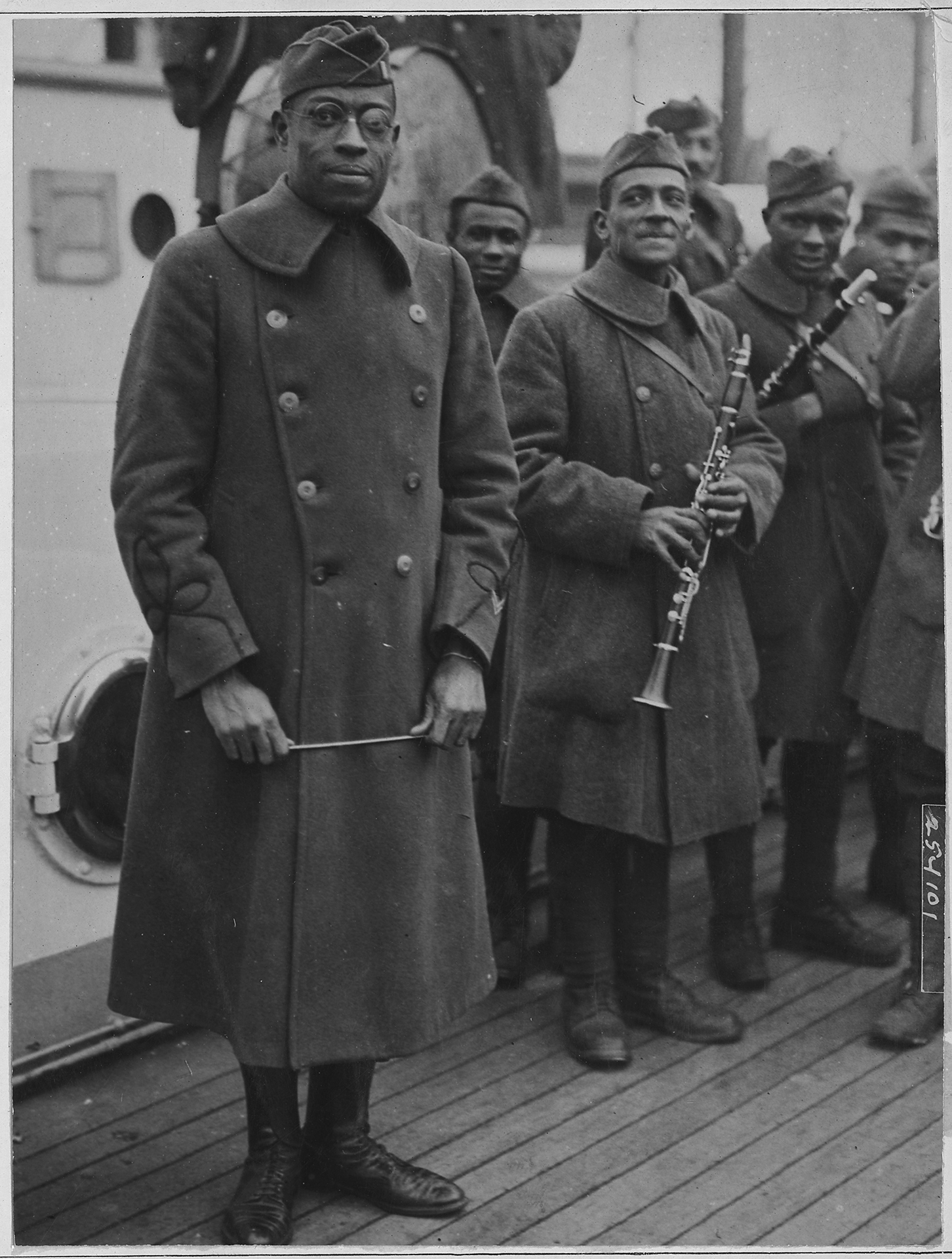

By 1916, the dogs of war were gathering. Europe enlisted in the U.S. Army as a private and was charged with assembling an Army band to encourage enlistment. He was given a substantial budget. Europe spent some of it on a recruiting trip to Puerto Rico when he got wind of musicians who were rumored to be the best reed players in the world. He brought back 18 top-notch musicians to flesh out the 15th New York National Guard Regiment’s band.

Before the war, Europe had said, “If I live to come back, I will startle the world with my music.” After the war, he declared, “We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others. And if we are to develop in America, we must develop along our own lines.”

Europe’s band was refused participation in the New York National Guard’s farewell parade down Fifth Avenue. An officer told Europe, “Black is not one of the colors of the rainbow.” Once overseas, Europe’s regiment was billeted to the French Army, the better to soothe the tender feelings of white American troops who refused to serve with Black soldiers. The camaraderie between the French and Europe’s regiment — newly renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment and among the first Black troops to serve in the War — was just one instance of Black soldiers experiencing a break from America’s racial illness. Their encounters would later have profound implications for Black America and the Civil Rights Movement.

Their French comrades soon dubbed the 369th the Harlem Hellfighters, with the recently promoted Lt. Europe distinguishing himself as the first Black man to lead combat troops during WWI. Finally, in a rare display of military intelligence, the Army recognized Europe’s true value and returned the 369th to its original mission as musical ambassadors. At their first performance, the Hellfighters played a syncopated version of “Le Marseilles” that knocked the French listeners sideways.

The Hellfighters’ band performed all over Europe (the place) for civilian audiences and Allied troops. It was Europe the place’s first exposure to the music that Europe the man helped create. One French orchestra tried and failed to replicate the Hellfighter sound with scores provided by Europe. A few skeptical French musicians insisted on examining what they suspected were Europe’s “trick instruments” before conceding that their distrust was a mistake. The Hellfighters were leaving a deeper impression with their instruments than their weapons.

At war’s end, the 369th Regiment was the first to march into Germany. A week later, the Hellfighters marched in front of ecstatic crowds in the Victory Parade in New York, vindication for the pre-War parade snub.

Before the war, Europe had said, “If I live to come back, I will startle the world with my music.” After the war, he declared, “We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others. And if we are to develop in America, we must develop along our own lines.” Europe had plans.

The following spring, Europe and team found themselves in Brooklyn to record 30 sides for Pathé Records before setting out on a two-month tour. He was working on a new National Negro Symphony Orchestra and was planning a Broadway musical with his partners Noble Sissle, who had also been in the trenches, and Eubie Blake. (Incidentally, Blake credited Europe with coining the term “gig” and often referred to him as “the Martin Luther King of music.”)

But none of that would come to pass. On May 9, 1919, during an intermission at a performance in Boston, one of Europe’s drummers, convinced he was being underpaid, stabbed the genius in the neck with a small pen knife. No one suspected the severity of the wound, with Europe encouraging the band to play on and complete the show as he was carried away on a stretcher.

An hour later, James Reese Europe was dead, his passing making headlines around the world. He became the first Black man to receive a public funeral in New York. He also received military honors at his interment at Arlington National Cemetery.

At his death, the word “jazz” had just begun to apply to Black musicians, having originally referred to the music of white copycat groups like the Original Dixieland Jass (sic) Band, which has been widely and erroneously credited as the first recorded jazz group. But just as Europe had predated the “jazz” of white musicians at Carnegie Hall, his 1913-14 recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company appeared well ahead of the “Original” Dixieland’s sides.

Moran first learned of Europe’s central importance from the late, great jazz pianist Randy Weston. As his Fats Waller project demonstrated, Moran is wise to the trap of treating his subjects like precious museum pieces. For all his deeply steeped understanding of the tradition, Moran is a modernist, and the performances on “From the Dancehall to the Battlefield” manage the delicate balance between reverence and relevance.

Moran’s respect for Europe’s legacy is apparent, and the blend of his Bandwagon Trio and an expanded lineup of reeds and brass highlights the anticipatory brilliance of Europe’s music. “Russian Rag,” an interpolation of a Rachmaninoff prelude, sets off as a basic ragtime romp that stretches until its seams burst. The juxtaposition of “Flee as a Bird to Your Mountain” — a piece the 369th played to honor fallen comrades — alongside Albert Ayler’s “Ghosts” connects the dots between Europe’s embryonic jazz and the ecstatic post-modernism of Ayler. Any notion that Europe was somehow “pre-jazz” should be laid to rest once and for all. Moran’s label “the Big Bang of Jazz” should be the first thing we think of when we recall Lt. James Reese Europe.

But those are just words. The proof is in the music. “All of No Man’s Land Is Ours,” composed literally in the trenches by Europe and Sissle, was a jaunty pop lyric sung by a soldier come home at last. Moran takes it instead as an elegiac solo. As its final strains hang like clouds, it seems the kind of music that had to have existed even before there were human ears around to hear it.

Go. Listen. Learn the history.

Rob Rushin-Knopf writes about music and culture at Immune to Boredom.