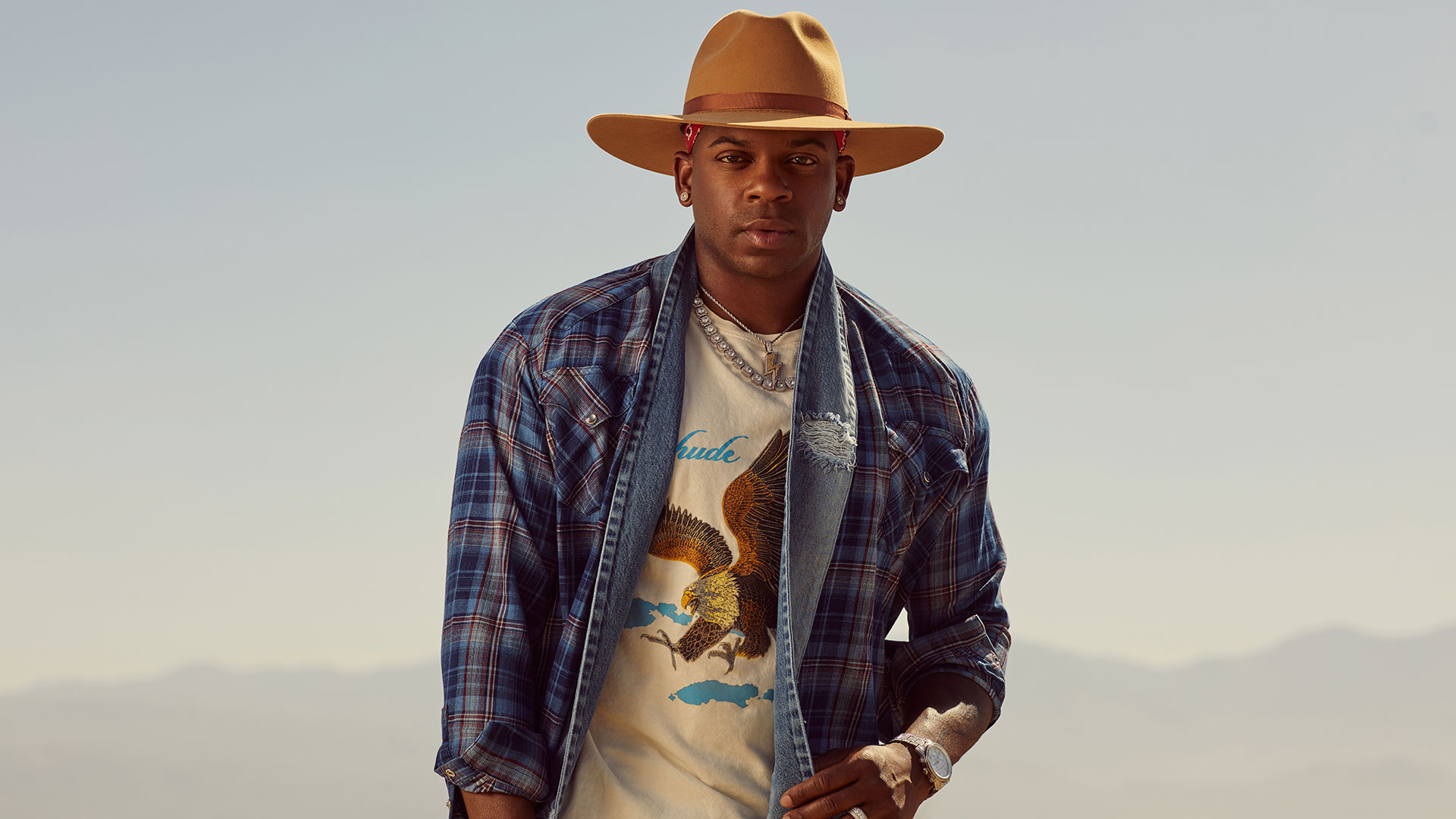

The Weight on Jimmie Allen’s Shoulders

The biggest Black star in country music knows his success puts a lot of responsibility in his lap. But he was raised right. He can handle it.

Over the last year, despite the pandemic, the country singer Jimmie Allen has been seemingly everywhere you look.

He’s competed on “Dancing With the Stars.” He published “My Voice Is a Trumpet,” a children’s book. He performed a duet with the late Charley Pride when Pride received the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award before his death in December of that year. Allen was back for performances at the 2021 CMA Awards, where he also co-anchored ABC’s Red Carpet coverage. He’s done all the usual major network morning and late-night stops, “The Macy’s Day Parade,” “Dick Clark’s Rockin’ New Year’s Eve” and toured the country as much as possible in these pandemic times.

He won the Country Music Association’s Best New Artist award in November, then became the only country nominee in any of the Grammy’s “Big Four” categories to be voted on by all members of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences. Now, he’s nominated for a Best New Artist Grammy alongside a diverse and formidable group: Olivia Rodrigo, Saweetie, the Kid LAROI, Japanese Breakfast, FINNEAS, Arlo Parks, Arooj Aftab, Baby Keem and Glass Animals.

And all the immense success Allen has enjoyed since his first hit — “Best Shot” — in 2018 has him thinking he might pull off a larger feat: widening the circle of what country music used to be to make it what it can be today.

“Most people hear with their eyes,” Jimmie Allen says, calling me on a rare day at home in Nashville. “They see a Black guy, and then they tell me they hear Charley Pride and Darius (Rucker), when the song is probably more Keith Urban or Pitbull. When skin color comes into play, people focus more on that than the music.”

Arriving in Nashville in 2007, Allen worked a variety of jobs, occasionally living in his car. So the profound nature of his Grammy nomination isn’t lost on the hard-working country hybridist. Yes, he’s recorded with Rucker and Pride, Urban, Tim McGraw and Little Big Town, but he’s also shared tracks with Nelly, Monica, Pitbull, Babyface and Noah Cyrus.

Me being Me

“It’s not about me being Black, but me being me,” he says, trying to address the secret sauce that defines — or even creates — his place in country music. “Everyone’s different. ... Growing up, it was me, two white kids and a Mexican. We’d go down to the pond or out on this boat fishing, and we’d listen to mix tapes. We’d go from Brooks & Dunn to Kirk Franklin to George Strait, Matchbox 20, Biggie.

“Growing up, it was me, two white kids and a Mexican. We’d go down to the pond or out on this boat fishing, and we’d listen to mix tapes.”

“We all got to know music and listen in its purest form, not about what you look like, or some idea of what we were supposed to want. It was pure, not who is it marketed to. And there were things in all of them we liked.”

He frequently cites lyrics and stories that capture life in small towns. His hometown of Milton, Delaware, on the Broadkill River, had a population was just over 500 when he was a kid, just under 3,000 today. His father raised him on a diet of Alan Jackson, Brooks & Dunn, Garth Brooks, Randy Travis and later Montgomery Gentry; his mother loved gospel music from the Gaither Family to Kirk Franklin and Frank Hammond.

“And I was into it all!” he enthuses. “Prince, Michael Jackson, Usher, Stevie Wonder, Earth, Wind & Fire, plus Matchbox 20, Three Doors Down and U2. Now I’m seeing country music getting back to the roots, storytelling and the blues. ... Take off the fiddles and steel guitars, just a piano and vocal, and you’ve got the blues.”

Allen is fluent when he talks about the history of country music — DeFord Bailey, the very first performer on the Grand Ole Opry and its first Black performer. He recognizes the idea that merging genres and influences reaches all the way back to Hank Williams Sr., who learned guitar from street musician Rufus Payne, who went by the name Tea Tot.

To the engaging Jimmie Allen, it’s natural, even inevitable, to blur lines and work the common ground. Unapologetically, the man who finally scored a publishing deal in 2016 when Ash Bowers spotted him at a writers’ night, explains, “It’s like making a smoothie. When you have things raw and uncoated, zero filler, they mix better. Or it’s like a milkshake, where everything’s all together and you don’t think about all the individual ingredients. It’s just delicious.”

What's in the Milkshake

That deliciousness is all over Bettie James Gold Edition, Allen’s latest album. It dips into caliente rhythms on “Flavor” with Pitbull featuring Vikina, or expansive pop on “This Is Us” with Noah Cyrus. There’s the 808-grounded stop/start, groove-centric “Good Times Roll.” Which belongs to his partner Nelly as to Allen. On the country tip, there’s Urban’s signature giddy up beat “Boy Gets a Truck,” McGraw’s rolling balladry “Made for These” and Brad Paisley’s sweeping ’90s surge “Freedom Was a Highway.”

It’s easy to be jaundiced in these times of marketing maximization. One artist from Column A, another from Column B; mix, match, swap audiences and hope to explode the metrics. Allen knows the potential read, but there’s so much joy when he speaks of every single artist who’s recorded with him, it’s hard to believe it’s merely an exploitation ploy.

He gets the suspicion, has seen hip hop artists dip into — perhaps — less-than-compelling country artists’ songs. Having been around town, Allen knows the power of alliances. But he’s also committed enough to his music to prominently feature the Oak Ridge Boys on the piano-anchored “When This Is Over” with Rita Wilson and Christian artist Tauren Wells; a pledge to transform adversity into a stronger community, it seeks a world where we all live more connected to one another.

“If you’re chasing things like country radio or awards or endorsements, that’s not music,” Allen says. “A great country song that moves you? That’s what I want. When something’s natural and authentic, it comes across.

“I want to let the artists I work with … I want to let their greatness be a part of what I’m creating,” Allen continues. “When I work with any artist, I want them to be them. These artists I’m a fan of, so I want them to bring what’s special about them to a song. That’s when it’s special.”

Allen has the same attitude about his live audience. Having toured with Kane Brown, Rascal Flatts, Chris Young and Brad Paisley, he waited to do his Down Home Tour until he felt he had enough reach to realize the audience he wanted to reach.

“My dream is to have people come to my concert no matter who they are,” he offers. “I literally stand onstage and take in the diversity. I see Black people in cowboy hats, in dreads and Timberlands. I’ll see Asians and Mexicans looking like they’re going to the rodeo or just anywhere, see white guys who look like they’d never go to a country show, only Kanye or Jay-Z. I’ll pick out two or three every night: a white person who looks like a ‘Country Fan’ and one who doesn’t, a Black guy in Jordans and one in cowboy boots. I’ll ask them how they got here. For some, it was ‘Good Time’ with Nelly, or the Tim McGraw song, or something that was more Christian. That’s what they come for, but then they like so much more.”

Allen slows down a little, considering the conversation he’s found himself in. He is aware that he is a Black man in a white genre. He knows he represents so much more than the obvious. He hopes that, perhaps, he can be more than merely a genuflection in front of country music’s need to evolve. He balances his own personal truth with the larger responsibility he carries.

It’s a lot, but it’s Jimmie Allen’s reality.

“We all say we want the world to be a better place, but then don’t want to do the work,” Allen says. “My ultimate goal is harmony. I love music and entertaining. Bringing people together like this is the first step. My dream is for people to come to my concerts, to have a good time — obviously — but also to feel more motivated to chase whatever dream they may have, maybe to accept themselves as they are, because if you can’t love yourself, how can you love anyone else?

“I had a buddy who said to me, ‘You are a Black man who has a Grammy nomination because of your success in country music. ... Think about that, because you have the ability to inspire so many people to go out and live the life they want. Whether people like you or your music, that is living your dream.’ And it’s true: I have a platform to inspire some Black kid, some Asian kid to come be a country artist, because they can see me.

“People can come together at my shows. No matter what brought them to a show, there’s something in my songs making each and every person feel like they’re a part of it ... and then they’re all connected through this music.”

The weight of responsibility

Allen stops, making sure his point sinks in. For all the good spirits and talk of songwriting, of weaving rhythms and seeking the proper message point, there’s a larger – often unspoken – hope that underscores Allen’s music. He knows he can bring more people who don’t follow the obvious tropes into the genre; earlier, he explained he hoped he could change the definition of an American to something that wasn’t just white skin and blond hair.

He knows it’s not as simple as throwing a switch, booking people like himself, Mickey Guyton, Allison Russell on awards shows or tours. For real change, it’s about deepening the conversation — and recognizing the more complicated realities in a genre that is largely listened to by white people.

“Having the weight of responsibility as a fan of country music,” he offers, “all the negative things you hear about country music aren’t true. There’s a lot of good people listening to country music, supporting my music and that’s part of it.

“I have this success because there are a whole lot of white people supporting me. Without those people in the business coming to the shows and listening to the music, I wouldn’t be here. And that’s true, too.

“Country music is who I am; it’s where I’m from,” he continues. “We’re all different, and all have different paths. But we’re all people. I feel like I have this responsibility because I’ve chosen it. My father said, ‘You’ve been raised the way you were for a reason... Letting young Black kids seeing you is saying, ‘You can do this.’ For a lot of young white people, you may be the person who gets them to question why Black people, Asian or Mexican people weren’t doing that...’

“To me, that’s where the change starts to actually take hold.”

Holly Gleason is a Nashville-based writer. Recipient of the Los Angeles Press Club's Southern California 2023 Entertainment Journalist of the Year, Music Criticism and Best Entertainment Feature, News (Magazine) Awards, she was the editor and a contributor to Woman Walk the Line: How the Women of Country Music Changed Our Lives, which won the Belmont Books Award for best country/roots music book, and co-authored Miranda Lambert's New York Times best-seller Y'all Eat Yet? She's written for Rolling Stone, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, Oxford American, No Depression, Paste, Texas Music, Spin, Musician, CREEM, Interview, Playboy, the Palm Beach Daily News, the Vineyard Gazette, Harpers Bazaar, Rock & Soul, and Mix.