“Charlie, Y’all Come Home”

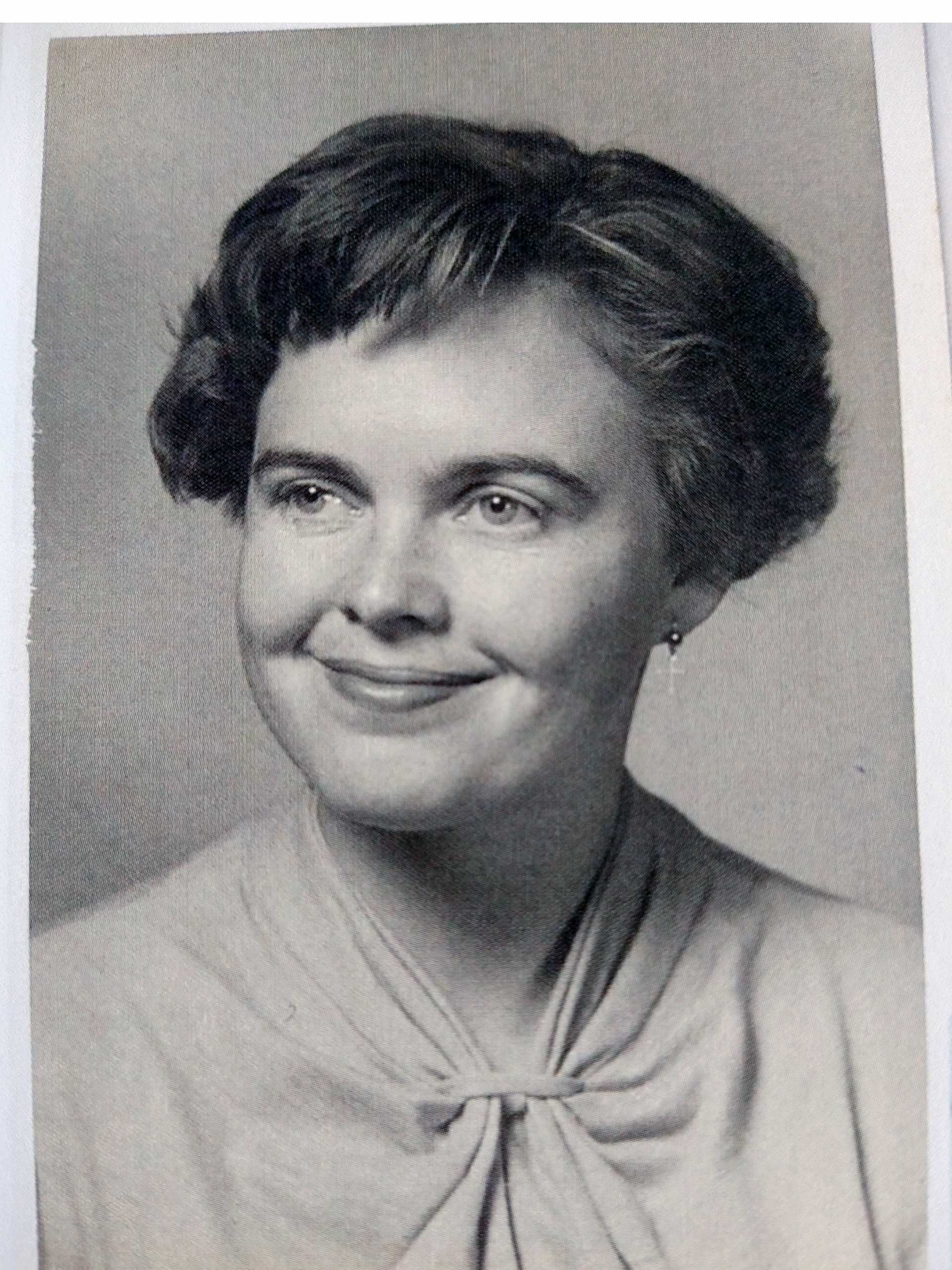

Charles McNair and his siblings cared for their mother in her home as she neared death. Her memories had faded, but the lessons she taught them grew stronger.

Charlie?

The voice was familiar — the first one I ever heard.

What, Mama?

I got to tee-tee.

In the last 18 months of my mother’s life, I spent many nights with her. She called my name, and I roused myself from bed to help her trundle to the bathroom on an aluminum walker. We went two or three times a night. I slipped down her diaper, or else changed it. I waited by the bathroom door, then made sure she got back to bed without falling.

At 87, Mama had care by committee. My five brothers and sisters and I took weeklong shifts with her. For nearly two years, I flew up every six weeks from my home in Bogotá, Colombia. I became intimately familiar with Delta 980 non-stop to Atlanta, four hours, más o menos. Alamo Car Rental got me from Hartsfield-Jackson to the McNair home on West Main Street in Dothan, Alabama. Another four hours.

I saw Mama fade away in snapshots. She seemed a little tinier every six weeks when I buckled her seat belt in the aging green Honda CRV she loved, when she could still go for a morning joyride. We ritually stopped for her forbidden fast-food biscuit and jelly. After that, we just drove, Mama perched in the front passenger seat with oversized sunglasses and a ratty sweater with dollar bills stuffed in the breast pocket.

"I always trusted there would be plenty of time to ask that question, to have that talk. I waited too long."

She liked to go to Jack’s Drug Store for her pills. She liked to go by the old church. She liked to take the nostalgic turn off Cottonwood Road onto Parish Street, where the McNairs lived for 12 years. There were eight of us there for a while … in a house with one bathroom. We lived on a dirt street with 100 acres of woods behind us.

On our rambles down memory lane, Mama mostly told the same stories.

There’s where the Forehands live – you know Brucie went to prison. There’s the Piggly. That’s where they showed “Walking Tall.”

I asked a serious question now and then.

Mama, where were you when you found out you were going to have me? That you were expecting?

Mama searched her mind. The little Honda engine idled.

I don’t remember.

Whole lifetimes – 87 years of hers and 66 years of mine – had passed. I always trusted there would be plenty of time to ask that question, to have that talk.

I waited too long.

~~~

Nora Joyce McCrory got pregnant out of wedlock. In 1953 America, that shame could follow a person through an entire lifetime.

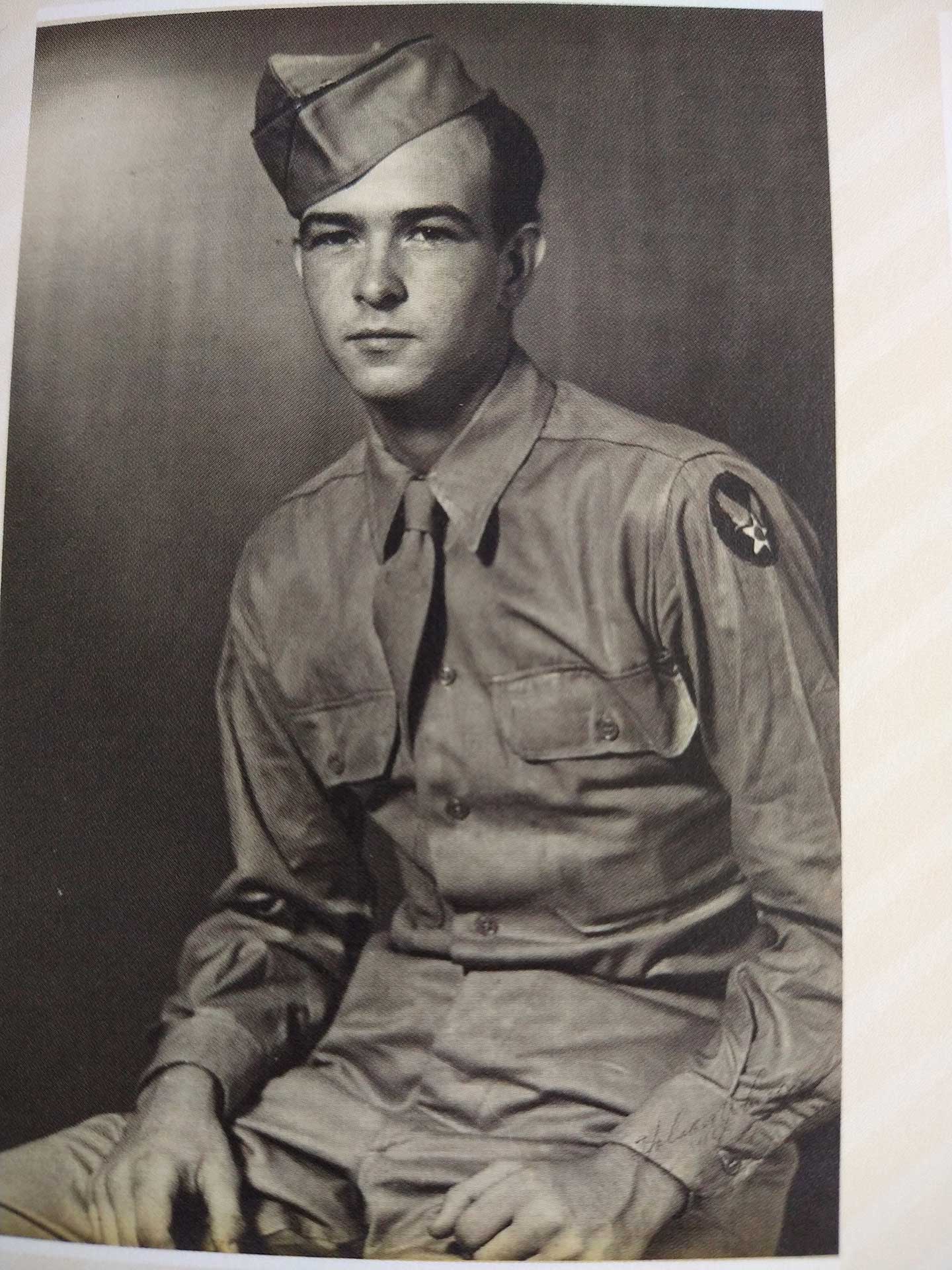

Bill and Dee, Mama’s parents, drove to Troy, Alabama, where Nora Joyce had newly graduated from the teacher’s college. They had a sit-down with the father and step-mother of my namesake … and my father, Charles McNair.

I can only imagine that excruciating 30 minutes.

Soon after, Daddy, a 20-something young buck back from two Philippine tours with the U.S. Army Air Corps, did right by Nora Joyce. They drove together to Lucedale, Mississippi, and found a justice of the peace. They spent their honeymoon night in a place they called the Rocky Mountain Hotel.

After that, Daddy disappeared.

I always heard he joined the U.S. Inspection Service and went off to Long Island to grade cherries. Mama took her teaching certificate and her growing belly to a high school in Samford, Florida. Alone. Anonymous.

She coached the girls’ basketball team. She wrote letters to Long Island and waited for a reply. She rubbed her tummy and spoke to unborn me.

Charlie?

That kind, familiar voice.

~~~

I came into the world at Frasier-Ellis Hospital in Dothan, a converted two-story house with hospital beds, one cold, rainy Thursday in January. I’m told that a bowl of red camellia blossoms brightened the room, and that Dr. Latolais arranged for medical students to witness the delivery. They applauded my birth. I hope it was for Mama.

She returned to Florida — Cocoa Beach now — and teaching. She still waited on a letter from Long Island. She passed time teasing my red hair into a rooster comb for Brownie Instamatic photos. She introduced me to scrambled eggs. Mama always loved cats, and we had a big orange one named Rusty.

One evening after about a year, Mama heard a knock on the door. A man stood behind the screen who looked, she always insisted, something like the actor Robert Taylor.

Daddy came home.

He and Mama would live together the next six decades. They had five more children after me – Clay and Robin, the boys, then Carole, Melody, and Marella. They lost another baby to a sad miscarriage.

We moved back to Dothan when I was 3. Daddy built houses. Mama kept house.

They endured parenthood and health crises and a few legendarily awful family vacation trips and the gradual losses of their loved ones. Together, they watched grandchildren come into being … then Mama, by herself, watched great-grandchildren come.

Mama saw familiar things disappear too. Things she knew and understood. Green stamps. Rabbit ears. Fizzies.

And memories.

Another question never asked?

Mama, what made Daddy come back from Long Island, after all that time?

My baby sister Marella once said the most beautiful thing when I asked that question.

Maybe, she said, Daddy fell in love with you.

~~~

We lived on Parish Street from 1960 to 1972. I was 5 when we moved in.

The house had beige asbestos-tile siding. It sat in a clearing hacked from the woods. We kept a fire pit in back where we burned our trash. Mama had four babies in five years. We raised chickens and turkeys and, now and then, hateful calves.

Memories of Mama are vivid from those years.

She woke me one icy-cold night, and we shivered to the end of the frozen red clay street as far as Mr. Massey’s field. She pointed to a comet. She wanted me to see a comet in my lifetime.

In early summer, Mama led expeditions to pick blackberries. We came home with our hands murder-red. At night, we scratched redbugs.

Mama slipped me a quarter the first day of the month, and I literally ran up to Mr. Brannon’s store and bought my favorite new Marvel comics, “Fantastic Four” and “Dr. Strange,” just 12 cents each. I learned to write from comic books.

Mama bought me a rubber ball and a glove somewhere, and I got to be a pretty good shortstop fielding grounders off the back steps in imaginary nine-inning games. (Bases loaded! Seventh game of the World Series! Batter swings! A sharp ground ball! McNair gloves it, deep in the hole …!)

Mama buried our pets with us, mostly poor cats, and we cried, and she always said a prayer.

Mama forced clumsy, strange things called shoes onto our feet every Sunday morning. Daddy dropped us off at Lafayette Street Methodist, where Brother Carmichael graphically described the Hell we’d go to if we didn’t always do what Mama said.

I saw Mama’s unconditional kindness, her loving nature, in so many ways.

One morning, she went to hang out clothes. A monkey balanced on the clothesline.

Mama recognized this notorious character from the local news. The Capuchin had been trained to ride shotgun on the back of a neighbor’s motorcycle. It finally had enough. The creature leapt off the bike, bit a kid down the street (21 shots in the stomach for rabies! yelled our neighbor, the paregoric addict), then for days eluded manhunts by flashlight and bloodhound through our woods.

Mama set down the clothes basket and went back in the house. She returned with a banana. The monkey took it obligingly, gobbled it, and left a yellow peel draped on the clothesline by the baby diapers. It then scrambled off into the woods and was lost to south Alabama history.

Mama let the McNair young’uns spend glorious summer days in those same deep woods. We played until long after dark. Every night, a freight train played that low harmonica where the woods ended, out where terrifying hoboes haunted the tracks. While lightning bugs seltzered the night, we told ghost stories (learned from Mama, of course) under a big sweetgum tree. Just when we got too scared for our skins, we heard a saving voice.

Charlie! Chaaaarrrlliieee! Y’all come home!

We sprinted. Mama waited on the back steps under a bare light bulb, a halo of summer moths around her head.

Chaaaarrrlliieee!

~~~

She guided us in sickness and in health.

Looking back, our Deep South ailments seem memorably preposterous. We children suffered a couple of bone fractures, of course, but what’s a snapped radius or two among a half dozen rough-and-tumble floor rats? (I don’t remember a single rug in our Parish Street house.)

The routine ailments were those Southern things so abhorrent to people elsewhere. Hookworms. Pinworms. Sandworms. Roundworms. When you run through Dixie with no shoes, sooner or later a wormy bill comes due.

So, too, with poison ivy and poison oak. We had our itchy share. And if no woodland vine troubled the skin, we troubled it ourselves. At least twice in my memory, my scratching of a thousand summer mosquito bites led to impetigo.

Every summer, we shared conjunctivitis, called “sore eyes” in my family. Nimbus clouds of gnats spread that plague from one child to the next. Some mornings, all the McNairs woke like newborn kittens, unable to open our eyes completely. Mama came around with a warm bath rag to melt the crust away and get us back out into the world.

She nursed four kids at once through mumps, chicken pox, and measles. We got blistered at Panama City Beach so bad that our shoulders and lips bubbled. When a basket of fresh peaches showed up on the porch, we ate so many, so fast, that we broke out in hives.

Baseball season brought scabs on knees and elbows. Those weren’t nearly as bad as Mama’s treatment — a fiery hot tincture called merthiolate. (The FDA banned this household medicine in the late 1990s when doctors figured out the mercury in it did worse damage than germs.)

Mama painted merthiolate on anything — an itchy bump, a rusty nail puncture, a bloody fresh strawberry on the knee. Merthiolate burned like fire from Hell. Mama blew on our wounds to cool the pain, and she said soothing things like That stinging is all the germs dying.

And … on the subject of Hell…

One night, I got scared the Devil was going to get me. I had listened to Brother Carmichael’s sermon. That stuff got to me.

In terrible fear, I called Mama. She climbed out of a warm bed and came through the house and sat by me and stroked my hair. She told me that the Devil could never get any child as long as his mama loves him.

And that meant the Devil would never get me.

Mama sat by my bed that night.

Then came my turn to sit by her bed.

~~~

Pancreatic.

The doctors called it that, though I don’t think any of us children ever saw a conclusive test. Mama, at age 87, was a house of cards (diabetes, high blood pressure, congestive heart issues), a familiar face in wards and rehabs for many months. Maybe she didn’t seem worth a lot of effort.

We brought her home to West Main. My sisters got a gurney bed that raised and lowered, and we set it up in the room next to the one where Daddy had passed away 14 years earlier. (My brother, Robin, would pass away in that same room less than 10 months later.)

I had always heard that pancreatic cancer brought excruciating pain. It’s lethal, certainly. It took Mama in just 23 days.

But she either bluffed a good game, or the pain didn’t much touch her.

Mama watched beloved reruns of “The Andy Griffith Show” and “Gunsmoke.” At night, she wanted “Wheel of Fortune“ and “Everybody Loves Raymond.” Every bedtime, she tuned to the 10 o’clock WTVY news.

In the way she showed us how to live with kindness, she showed us how to die with grace.

One night, on my shift, she woke, wide-eyed, and started singing a hymn from the Cokesbury hymnal of her youth.

In my heart, there rings a melody.

There rings a melody

With heaven’s harmony.

In my heart there rings a melody.

There rings a melody

Of love.

~~~

Early in April 2019, Mama passed.

I and my sweet Colombian wife, Adela, and my baby sister, Marella, slept in her room that night. We knew from hospice that the end would come soon. The three of us — Mama’s oldest and youngest children, the redheads, and a daughter-in-law she loved because they shared the same birthday — held vigil.

When Mama’s breathing stopped, it woke us. The loudest silence.

I delivered the eulogy at her funeral. It was the hardest thing I ever did, and it is the proudest thing I ever did.

Here’s part of the commemoration:

Mama’s gone to Heaven, if anybody ever went. She’s with the angel band.

Now … Heaven. We don’t really know what it’s like there.

Personally, I think Mama would be bored by streets paved with gold and pearly gates.

I’m thinking Mama’s Heaven has a lot of cats. Every baby has red hair. She sits on the edge of the bed as the sun rises and watches cars pass the house. She gets a Happy Meal and saves prizes for her great-grandbabies.

She takes a ride on Thursday to a beauty parlor to get her hair gussied up, and on Friday … every Friday … she eats fish. Saturday, there’s Alabama and Auburn football. Sunday, she drops off an envelope at the church with two wadded-up $5 bills inside … and she brings home a church bulletin.

It was so easy to make Mama happy, wasn’t it? She was so simple in her tastes, so childlike in her affections. So good in her heart.

All you really had to do to be a friend of Nora Joyce was to try to be good in your heart too.

Isn’t that the gift she leaves us all? The great secret of happiness?

Just be kind.

Always. Every time. No exceptions. To friends and family. To the young, thirsty Mormon missionaries who come to the door. To the Black restaurant worker you teach as a substitute, who never forgets you. To the Colombian family without a word of English that your son brings into your world. To the kids with Down syndrome you teach for months as a substitute in a special-needs class.

To total strangers. To rich or poor, happy or sad, better or worse.

Just be kind.

Just be kind. I’ve thought a lot these past several years … these curious times … about that notion. About just being kind. About unconditional kindness. About a kindness that passes all understanding.

It seems to me our salvation.