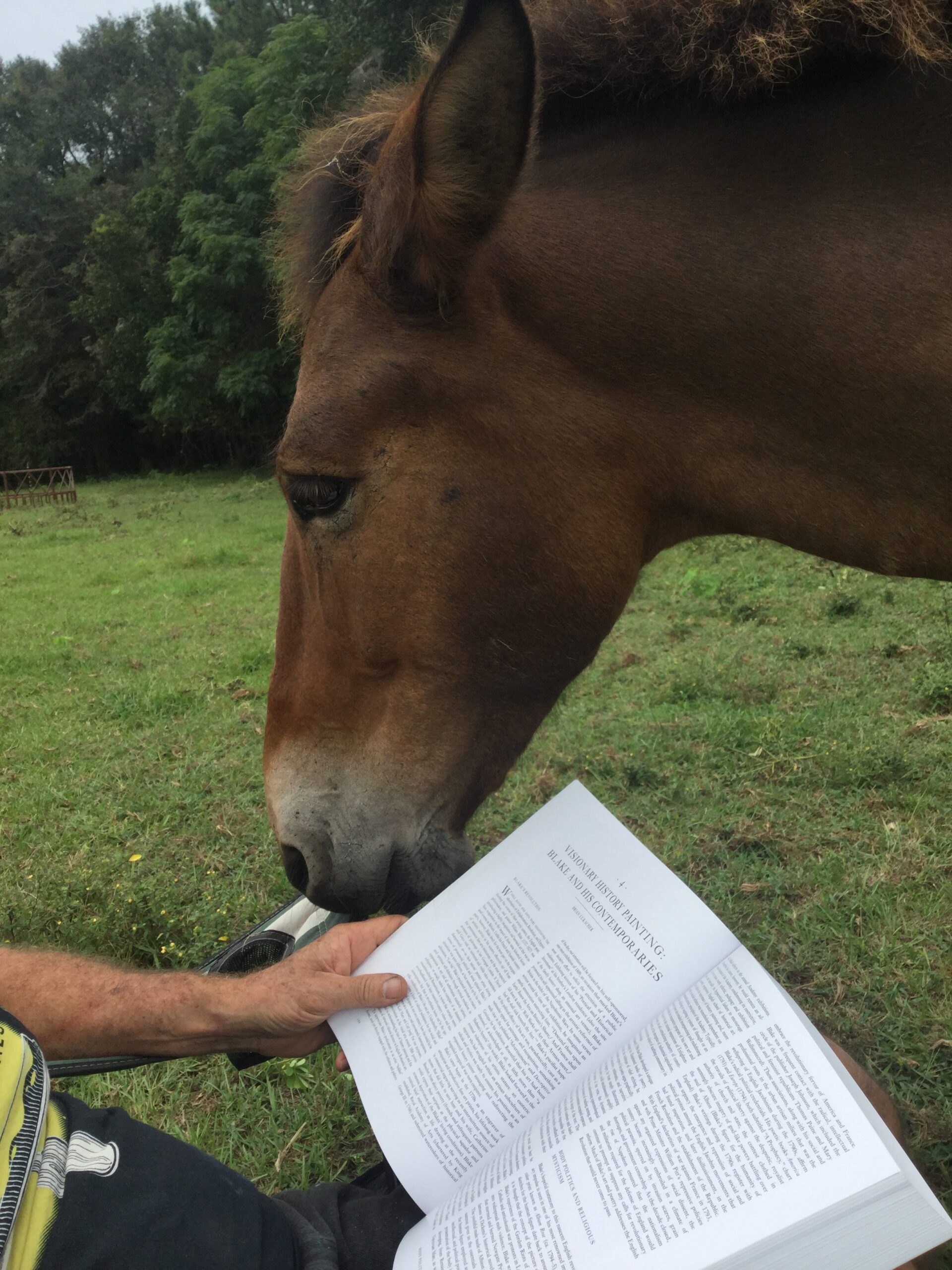

A Recalcitrant Mule

Just like a mule to get stuck on a porch. And like a kid to put him there.

This happened the evening our young neighbors came over for a kombucha culture. The husband, an iron man by trade and athletics, had got a juicer for Christmas and I asked if he wanted greens. He said yes, so we walked out to the garden. Leaves were not yet back on the pecan trees, which stick like gray armatures out of the ground five months of the year. Although the grass was brown and dead in the pastures, in the garden the collards and mustards threw up green leaves large enough to fan emperors.

I saw my kid running for the cow pasture. I wasn’t sure why, so I yelled at her to come back. Bobby and I went into the garden, and by the time we came out, arms loaded with kale, my kid had ignored my order. She was leading our mule across the yard.

What are you doing? I hollered. Take him back. My neighbor didn’t realize what a situation this could become — I was stuck between trying to listen to him and still keep my kid out of the emergency room.

Can I put him in the dog run for now? she said. My kid is a blond pixie with a face so cherubic it lays a trap.

That’s fine. Then come inside.

My neighbor and I went into the house and I, expecting blind obedience, forgot about my kid until a few minutes later. Strange hammering sounds, like very heavy staccato dancing, came from the breezeway.

What in the world? I said.

My kid appeared at the door, her pretty face up against the glass. Then another face, a strange animal countenance, appeared next to her. Two sets of eyes glittered with eagerness as they peered in the door, one pair of eyes small and green, the other large and brown. A set of large, furry ears were tuned to whatever lay ahead.

A mule is a comical thing. Ours is smallish, maybe 14 hands, a size that contributes to a frightful agility. In the pasture he lopes around as if on roller skates. I’ve seen him punting with four razor-edged hooves in the air. I’ve seen him folded sideways off the ground. I’ve seen him standing on his front legs. He will balance on two hind-legs and nip sand pears off the old tree. Plus, as a kicker, he has impeccable, award-winning, sniper-like aim. I’ve been struck by him more than once.

He’s an odd kind of being. I gave up training him because I couldn’t get a bead on him. He wouldn’t bond, wouldn’t obey, usually wouldn’t even look at me.

The guy who runs the livestock sale, Louie, a man with a 10-gallon hat and a handlebar mustache, is the one who gave him to us. If you want him, I’m throwing in the red mule, he said, when we bought our first horse, Cheyenne, an Appaloosa. Free of charge.

We were equine idiots and a little zany too.

Louie’s hired man, a placid young cowboy named Ephraim, who wears plaid shirts and ostrich boots, had worked with horses back in Mexico. He had tried starting the mule, even riding him, Louie told us, but Ephraim couldn’t get anywhere. The mule’s fate was the meat buyers, and I guess Louie felt some kindness toward him or he wouldn’t have offered him up.

Only way to work a mule is to beat ’em every day with a two by four, an old guy told us. You can teach a mule all day, another old guy said, and next morning you’ve got to start over. Somebody else said, A mule will work hard 10 years for one chance to kick the hell out of you.

The day we got him, he let us put a halter on him and lead him into a borrowed horse trailer as if he were a thoroughbred. We led him out of the trailer and into our paddock in the same demure fashion. After that, like some marriages I’ve heard of, he let his true colors shine. He bit, he bucked, he slung the barrel of his body in circles, he laid back his ears at mention of approach. I ran him in the round pen, and every time he passed me, he shot a hoof or two in my direction.

We named him Tecumseh.

Next time we saw Louie, we asked about the mule’s history.

I got him in a trade, he said, when he was a colt. Trouble was, he was pastured with stallions and from a young age he had to fight the big boys. Plus he’s never been gelded.

I thought mules were sterile, I said.

They still produce testosterone, Louie said and made a large horseshoe with his mustache.

Okay, we’re gonna fix him, we said. We trailered Tecumseh to Dublin, two hours away, so he could take part in a free clinic, as in spay your cat, sterilize your mule.

He came back meaner than ever. He lashed out at Cheyenne, and then the other horses since we had acquired three more, so much that he had to be pastured with the cows. His afternoon entertainment was to sprint after the yearlings, who dashed this way and that until they finally hid in the shadow of the ox, the only animal bigger than the mule. Somebody told us that getting the testosterone out of Tecumseh’s system might take a couple of years.

We tried half-heartedly to re-gift him. In some strange way, however, we understood Tecumseh. Something had happened to him. He’d had to fight for his life from a young age and he couldn’t stop fighting. His brain had been bathed in tough-guy chemicals. And of course, he was a mule.

Only way to work a mule is to beat ’em every day with a two by four, an old guy told us. You can teach a mule all day, another old guy said, and next morning you’ve got to start over. Somebody else said, A mule will work hard 10 years for one chance to kick the hell out of you.

Now he was on our breezeway, this recalcitrant mule, which he had accessed by willingly following his cohort, our kid, up a riser of steps to a porch three feet off the ground. At one end of the breezeway was a pair of French doors that led into a sunroom, in the main part of the house, and at the other end was a solid-glass door that opened into the kitchen. (Our kitchen is separated from the main house in the vernacular architecture of the colonial South.) We spend most of our time in the kitchen, which has a sofa and chairs, a woodstove, a stereo, and so forth.

Holy cracker, I said. Get him down, I hollered through the door at my kid, who had a proud grin on her face. Lead him down. The mule was grinning too, as if to say, I always wondered what this joint looked like.

My kid turned the mule. The gray-painted breezeway floor was slick to his hooves and he couldn’t get a good purchase. He crept to the steps, my kid holding his lead like a real cowpoke, and they stood looking down. At the bottom was a brick patio.

I’m not going down there, the mule thought. I could slip and bust my ass.

My kid pulled at the lead. Tecumseh planted his feet and looked like a tilted sign. His eyes widened and got crazy-looking.

My kid went down to the patio and pulled at the rope as hard as she could. Tecumseh dug in his heels and began to sling his head from side to side. Nothing good could come of this.

Suddenly everything was fragile. The recycling bin was full of glass, the solar oven was breakable, a wooden chair was matchsticks. A mule could wreck a chest freezer. I started speculating what new doors would cost. The thought flashed across my mind that house insurance might not even cover something like this.

My husband, Raven, a broad-chested and thin-waisted farmer, can sit patiently while all manner of chaos unfolds around him. He cultivates a habit of observing but not participating in the careening turns of a day. Raven, I said now.

He looked toward me with calm green eyes, cool as chinaberries.

I need you.

We pulled, pushed, begged, lured. We sweet-talked, we proffered feed-grain, hay, carrots, apples, and molasses, we smacked Tecumseh on the hindparts with a broom. Our neighbors tried to help. Truth be told, the descent looked dangerous to me too. If the mule slipped on the steps, or if he leapt from the breezeway to the bricks, he could easily break a leg, and that could end very badly.

The sun had slipped down behind the woods to the west. These days it was still setting toward the south. Bushy tips of pine trees were silhouetted against it.

Why did you bring him up here? I asked my kid in desperation.

You never told me I couldn’t, she said.

I have severely underestimated you, kid, I thought. I said aloud, Okay, here’s a new rule: Never bring a mule up on a porch. Or any kind of equine.

I had an afterthought. Or a bovine.

As night advanced, we turned on the porch lights, inside lights, security lights, everything. We wanted the mule to be able to see the ground, in case he decided to leap. He now clattered in skittering circles, agitated at the lead rope. We told our neighbors they should go on home, maybe we could talk about smoothies another time. When things quieted down the mule might step off. That, unfortunately, seemed like a long shot.

As stillness descended the mule’s panic grew. Nothing distracted him now from his predicament. He was hankering for solid ground, sweet grass, pasture-mates.

We had an idea. On the other side of the kitchen was a deck, slightly lower than the breezeway, and perhaps the mule would be better able to navigate those stairs. All we had to do was get him through the kitchen. We thought about that for a long time. Then Raven opened the glass door to the kitchen.

In extreme weather we allow our large hairy dogs inside. We bring in the drooling barn cat. We keep chicks in there in early spring, under a heat lamp, until their stench is unbearable. We warm lambs in the kitchen, feed motherless calves. We bring in kid goats, showing them off to guests.

Never has a full-grown mule been there.

I took the lead now, firmly, and started toward the door. If the mule freaked, I could hang like a dead weight on his rope. But I didn’t need him to freak. We stepped through the glass door, me at mean old Tecumseh’s head, him finally, for once, trusting me, or so it seemed. He put his hooves gingerly onto the pine floor and we started our journey.

Then we were through the door and fully into the kitchen. All we had to do was cross the room and get out one more set of glass doors.

My breathing was shallow. Tecumseh and I crept past a line of stools at a counter. We eased past a spice cabinet, packed with glass vials of cinnamon and cardamom. We lurched past a hand-hewn trestle table, past a woodstove’s glass inset. We tottered past a pottery vase full of thin-stemmed flowers, a shelf of knick-knacks, a line of antique crocks and churns. We eased alongside shelves of Mason jars filled with canned tomatoes and pickles. We tiptoed past a thin-legged buffet, past baby pictures of our children, past the glass-fronted china cabinet with its wine goblets, fluted bowls, salt cellars, gold-edged teacups, butter dishes, and my grandmother’s cow-shaped milk pitcher. The mule and I teetered past crystal so thin it rang like music.

As he followed me, the mule began to tiptoe, as if he could understand that his wasn’t the only trouble. I was in a mess too. He began to hold his breath. He looked at all the delicate and ornate objects around him, things he’d never seen, and he changed. For the first time in his life with me, he abandoned his meanness and his muleness, until I could tell by the way he stayed at my shoulder and the way that he placed each foot precisely and prudently that he too thought that maybe this wasn’t the place for tomfoolery.

We exited the kitchen via two French doors paired on each side with a full-length window of solid glass. I took in a big lungful of air and so did Tecumseh. Together we paused and looked off toward the marsh, where great egrets and wood storks will flower after heavy rains, where the spring choruses of frogs would soon deafen the woods. A leatherwing flapped past, zigzagging for insects. Somewhere in the woods across the dirt road a Chuck-will’s-widow would soon crank up its lonely, incessant call.

Who needs television? I thought.

For some reason I thought then of a recent traffic jam between Atlanta and Macon, miles of vehicles, six lanes of them, stalled, idling, each windshield a screen like a single blind eye and inside the vehicles more screens – a screen for a map, a screen for a phone, a screen for a camera, a screen for a book. Tecumseh and I stood breathing the wild perfume of Carolina jessamine, which blooms in late winter, each yellow blossom a throat, a yellow bugle, a vial, medicinal and omniscient.

But the mule had been misled. He thought that through the doors he’d been free. He was on the deck now, open to the indigo sky but still over two feet off the ground. He began to paw at the decking. He turned and stared inside the kitchen, then started kicking at the windows.

He doesn’t understand glass, Raven said. He thinks he can go through it.

I thought he could too. Cut the inside lights, I yelled to my kid.

Keep him still, Raven said. So I did.

Raven sprinted to the barn and came back on the tractor with full sheets of plywood, which he used to barricade the French doors and windows. Now we could try again to get Tecumseh down. I led him to the stairs. He strained backward against my pressure on his halter. Then he slipped. Miraculously he regained his footing. I pulled harder. The mule heaved and slid, then he went down to the deck with a terrible crash. He struggled back to his feet. He stood wide-eyed, ribs pumping, trapped.

He’s gonna get hurt, like this, Raven said. He swirled off on the tractor and came back with hay and scattered it over the deck. We’d done all we could do. We stood awhile as dusk came on, waiting for some other idea to come to us. None did. Finally, Raven said he was going to bring a bucket of water, which meant that our back deck was going to be Tecumseh’s pen for a while. We’ve done all we can do for tonight, Raven said. The three of us fumbled through chores in the dark, and when we returned from the barnyard, the mule was where we’d left him. He had pooped some.

Afraid to turn on lights, we ate a quick supper and went to bed.

Sleep did not come easily. Next morning when I woke, I didn’t feel my usual gratitude at being alive another day. I remembered instantly what loomed ahead. We could spend hours getting a mule out of our house.

Raven set to work, ignoring breakfast. An idea had come to him in the night. He constructed a ramp from the deck to the lawn, lined it with hay, and went off to the barn. He came back with a pail of sweet feed and placed it at the bottom of the ramp. Now the mule perked up. Molasses was one of his favorite smells. He could hear grains of corn and oats rattling against the galvanized sides of the pail. Raven’s plan was going to succeed, we could see right away. The mule was too interested in sweet feed for it not to work.

I wish I could say Tecumseh walked right down. He didn’t. He gracelessly slid with me at the bottom leaning my entire weight into a lead, Raven curving another rope around his hindquarters, pulling at his butt end. With a big clatter and a grunt, the mule dove for the pail. Finally, after a night in the slammer, he was free, back on solid ground, back in charge.

The kid had to clean the deck, which, in her words, was totally full of poop.

Since this happened to us, I have heard similar stories. Some kids at Reinhardt College got a cow up a set of stairs once, and naturally couldn’t get her down, at least not the normal way. That happened before an elevator was installed in the building. I heard about another kid who brought her pony into the house.

I learned a few things with this incident. You can bring a mule home but that may be all you can do with him. You can lead one to water but you can’t make him drink it from a saucer. Therefore, I have a piece of advice. If you want to add some pizzazz to a day, if you need a little dose of fun and adventure, if you don’t have enough challenge in your life, if things are too virtual, find yourself a mule. Find yourself a set of stairs.