Let It Be Declared

From South Carolina to Washington, D.C., a chronicle of poetic lineage and family history.

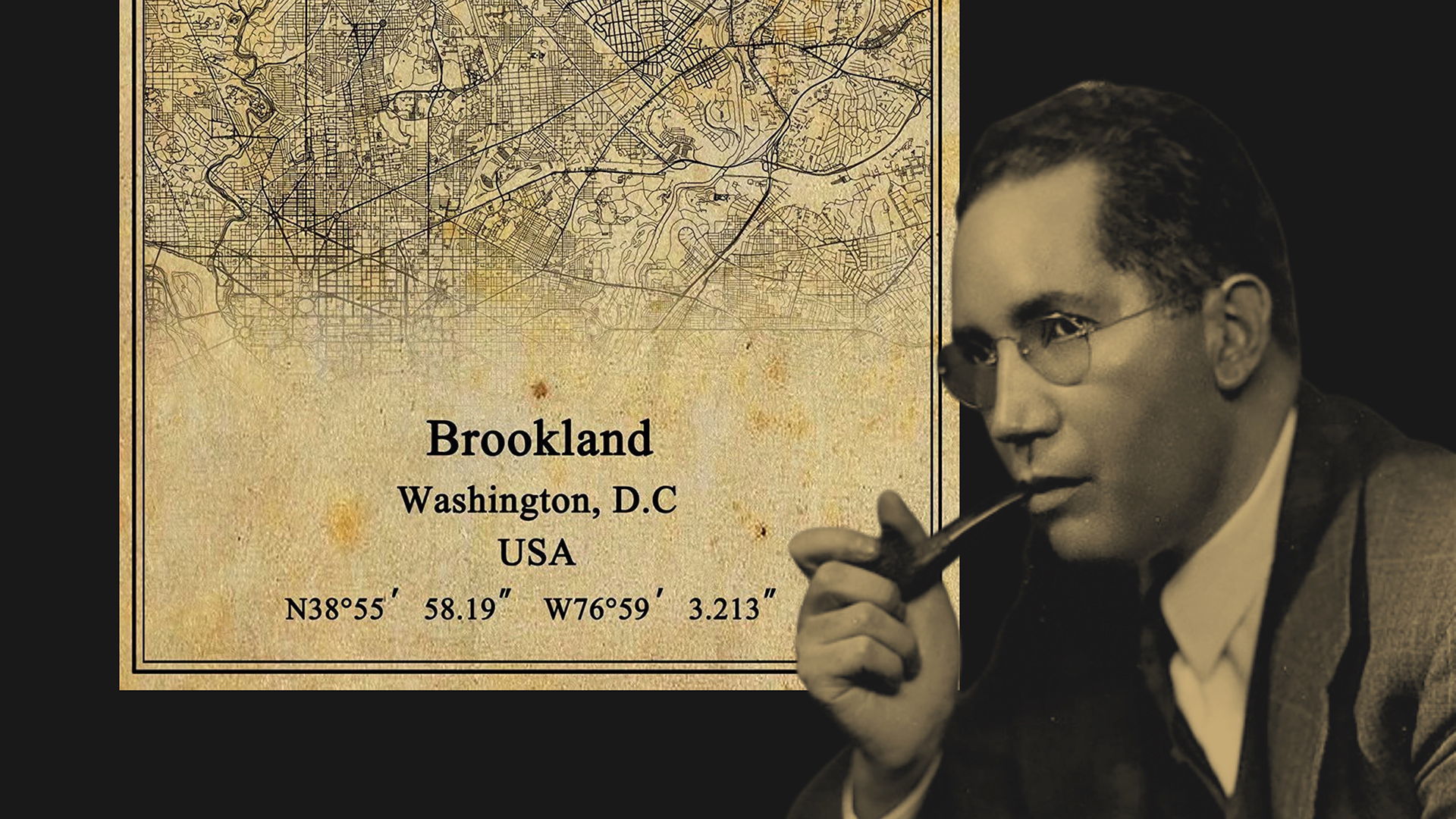

Sterling Brown: Uptown

In 1933, my grandmother and mother, who was just three years old, boarded a train somewhere in South Carolina, and came to live in Washington, D.C.

My mother was born in a small African American community in South Carolina called Santuc. The railroad tracks are just up the street from where she was born on a sharecropper’s (her grandparents’) farm. On the other side of the tracks was Union, South Carolina, the big city where the whites lived. In coming to Washington, my grandmother did not escape that segregated Jim Crow world. However, there was work for African Americans in Washington, and the city, full of Black professionals and strivers, was a good place for Black people in 1933 despite the Jim Crow realities.

One of those realities was racial segregation. Uptown was dominated by whites, while my mother and grandmother, like many of the African Americans in the early 1930s, lived downtown in the U Street corridor. My mother would not move from that neighborhood until the 1950s, but some African Americans, somehow, were able to move uptown a little earlier.

In 1935, the poet Sterling Brown purchased a house uptown at 1222 Kearney Street NE in an area called “The Little Vatican” by locals today, because of the many Catholic churches and organizations. The neighborhood is also called Brookland, and it became one tiny enclave of some equality in the city, especially for African American professionals.

Sterling A. Brown holds a special importance for many African American poets in Washington. In 1987, when I arrived back in the city from college in western Maryland and I declared I was a poet, I immediately became yet another poet who focused on Brown’s work and his example of the poet life. Everyone I knew who was a poet in the city knew about Brown. Some had even been invited to his home to sip bourbon and listen to blues recordings by Ma Rainey and other masters of the form.

I had heard of Brown before that also. My father, uncle, and older cousin all had attended Howard University and had taken classes from Sterling Brown in the 1950s. My father once chuckled to me that Brown had given him a “C” in English II. My cousin, Gilbert Minor, showed me a poem Brown had critiqued for him. Naturally, with all this hype, and firsthand chatter, I wanted to meet Brown, but he died in January 1989, and I never had the pleasure. I was just beginning to find my way as a poet, and the master of all bards in Washington had departed.

“My mother bought two lots in Brookland and built one home for herself and two daughters, and one for my wife, myself, and our adopted son. When the homes were completed, ‘For Sale’ signs in the neighborhood seemed to sprout overnight.”

Thereafter, I decided to learn as much as I could about Brown, the poet, expert of Black culture and history, and “race man,” as my father once said. I did learn that Brown’s integration of that Brookland neighborhood was not so smooth. The normal Jim Crow attitudes of America back then ruled the day. Brown made that clear when he responded to an essay by Jeremiah O’Leary, who—writing in the Washington Star—claimed the mass exodus of whites from the neighborhood was because of the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. Brown, with wit and style, begged to differ in a response published in the same newspaper:

The exodus of the Irish and WASPs cannot be blamed on Pearl Harbor. I am afraid that my family was one of the dire causes of white flight. Moving from our previous home when it was purchased by Howard University, my mother bought two lots in Brookland and built one home for herself and two daughters, and one for my wife, myself, and our adopted son. When the homes were completed, “For Sale” signs in the neighborhood seemed to sprout overnight.

To his credit, Brown was a true integrationist. He invited a diverse group of white, Black, and European individuals to his home for his blues and whiskey gatherings. Political scientist Ralph Bunche, sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, folklorist Ben Botkin, economist Gunnar Myrdal, writer Jerre Mangione, music producer and critic John Hammond, real estate developer Charles E. Smith, jazz writer and producer Fred Ramsey, editor Gordon Gullickson, and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax all found time for Brown at his famous Brookland home.

Brookland also had several other African Americans of note who bought homes there: Pearl Bailey, the singer; Rayford Logan, the history professor at Howard University; Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate in the twentieth century. Hilyard Robinson and Howard Mackey, two African American architects, built many homes in the neighborhood for several of them.

Somehow, before the official legal end of Jim Crow life in the 1950s, when my mother and grandmother moved uptown, a poet navigated the city’s challenging racial hierarchy. It looks like he did pretty well, too.

Sterling Brown’s House, Washington, D.C., 1990s (For Marcia Davis)

i came to live here in ’35. like hansberry’s

folks in chi-town. no bricks thrown through my

windows even though the WASPS & irish spell

“niger” with just one “g.” ‘what’s a “g” between

friends?’ they say. one noteworthy fool who

drove by slow screamed “naygur” as loud as he could.

many put signs on their lawns, or searched

quickly for sundown towns that could remove

the “exotic” from their memory.

but “count us in” anyway. count them out.

& let it be declared that everyone did not

succumb to the easy hate. professors from the

catholic college down the road did not join the

racial exodus. hammond & myrdal & lomax came

to drink bourbon from my pretty tall glasses.

i play my 78s all night for them. bessie & ma rainey

& louis armstrong. they marvel at my book

collections & the missing cracks & pops

from my vinyl. when the whiskey begins to work

like chicken soup for a head cold, the story of king oliver

dying broke mopping floors in obscurity in georgia

always comes up, followed by my confident dismissal of

“gone with the wind” as nothing more than

“the international jew” for black people.

i could have written more. but there is more to

this life than beats & lines, the incessant uneasiness

of iambic ideology. there are the children. what shall

become of us without sunflowers growing beautifully

abundant in grassy fields? & someone to know

armstrong’s “west end blues” like a recipe for cobbler

that has never been written down. this is our strength,

endurance, this is how we always overcome those

demented screams from slow moving cars.

This poem originally appeared in Beltway Poetry Quarterly. Thanks to editor Kim Roberts.

Letter to My Grandmother

Dear Grandma—

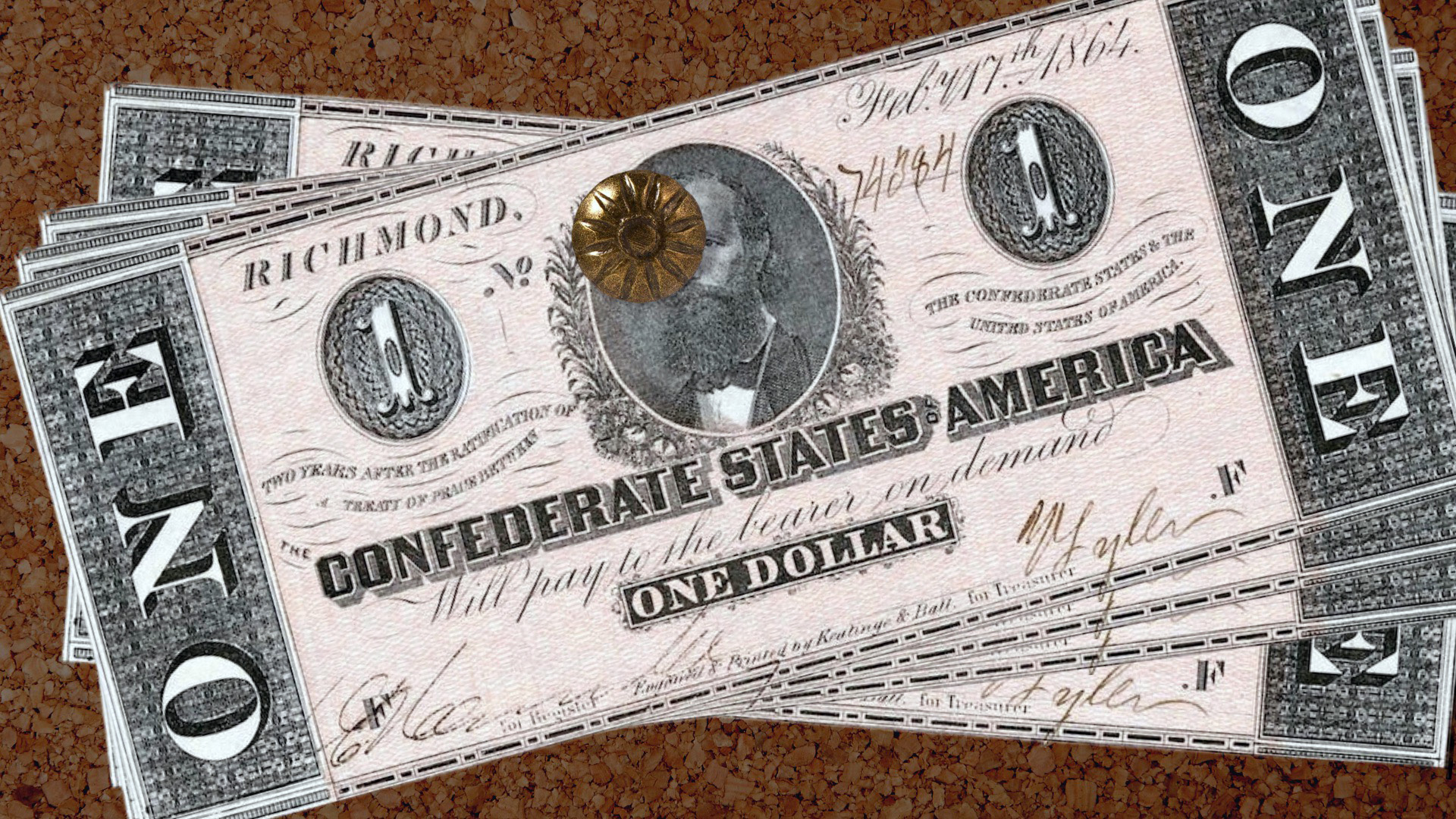

It all goes back to those Confederate dollar bills tacked on the wall in your home. Pinned on a small bulletin board in your kitchen. When I was a kid I would stare at them for hours and they seemed to be trying to tell a story.

You were a Black girl, born in South Carolina in 1912, in the heart of the old Confederacy in an all-Black enclave called Santuc. It is a village just outside of Union, South Carolina, and the one time I drove down there years ago, the community was so tiny it wasn’t even marked on a map. It was where all the Black people lived in your day and it was where your family worked hard each day just to make it, and they just barely made it each day.

The last time I was in South Carolina, there were so many Confederate flags waving from trucks and cars, I did not feel as if I was in America. It felt like I was in a different country, and the hate was suffocating.

I understand that now.

Those flags are in a lot of places in America (not everywhere) but South Carolina is just more honest. And if Confederate flags are everywhere now in South Carolina, I can’t even fathom how it was back when you were a girl. A young Black girl trying to navigate a gulag of a place and life. I know you swallowed all of it all those years and held it in.

In one of the few times where you did talk about your life growing up in Santuc, you talked of picking cotton for a nickel a week in the hot sun. You said your fingers bled from the cotton thorns until you got the hang of it. Fill the bags up all day in the hot sun. Five cents. And you gave that to your parents so the family could make it.

The Black people on the train had to sit in the “Colored” train car next to the coal car. My mother remembers because when she arrived in Washington, D.C., her dress, she said, was covered with black coal dust.

Your parents — the great-grandparents I never met — were sharecroppers. They didn’t even own the land they lived and worked on, but they had to work the land hard all day nearly every day just to put food on the table. That’s how your family of ten-plus ate each day.

Rise early when it was still dim or dark, milk the cows, get some eggs, get some food going. Everyone had to pitch in and work all day. That was life.

At the end of the year, they had to pay the owner. The landlord. They worked the land all year, harvested crops, and then all they had would go to the owner. Feudalism. Slavery by another name. And his only offering at the end: do it again next year.

You watched this year after year. By the time you were a teenager, your parents, you knew, were nearly dead. It was a tough life. Neither of them would make sixty. But even that was pretty amazing. But, you knew then you had to leave. It all had to end.

I remember my mother telling me she remembers leaving South Carolina. She recalls riding on the train up North a bit to Washington, D.C. The Black people on the train had to sit in the “Colored” train car next to the coal car. My mother remembers because when she arrived in Washington, D.C., her dress, she said, was covered with black coal dust.

I remember too when that film The Color Purple came on television, and you turned away from it as most of us watched. I didn’t understand back then. You didn’t watch a minute of it.

Later, my mother, your only child, told me that you turned away because a lot in the film was true. The beatings of Black women by men. The rapes of Black women by men. Black men tried to turn their wives and lovers into mules.

Black women were on the frontline of the fight for freedom but sometimes they also had to fight their men. The book and the movie got it right, my mother told me, and you didn’t need to see that movie to know.

I understand it now. Sad faces but also your big beautiful smiles. Your endurance through your chosen silence about the past and what you saw down in South Carolina growing up.

And I remember the fried chicken you cooked perfectly. I can still taste that now. The collard greens full of garlic and salt pork and scoops of sweet potato pie melting down my throat topped with vanilla ice cream you churned yourself.

But those Confederate dollar bills pinned to your wall. That’s what pulls it all together. Your life of hard work, pride, and your family love. Those dollars told you how hard you had worked to get out. How you would never go back to that life but it made you who you are.

I understand it now, Grandma. Believe me, I do. And I am forever grateful for the chance you gave me to make a good life.

Yours always,

About the author

Brian Gilmore is a Washington, D.C., poet and public interest lawyer. He is the author of four collections of poetry, including the latest, come see about me marvin (Wayne State University Press, 2019), a Michigan Notable Book for 2020. He is currently Senior Lecturer at the University of Maryland, College Park, in the MLAW Program and a contributing writer for The Progressive.