“Simply the Best” Wins LA Press Club Award

The legend from Nutbush, Tennessee, always knew what love had to do with it.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This remembrance of Tina Turner, written by Salvation South contributor Holly Gleason last spring after Turner's death, earlier this week won the Los Angeles Press Club Award for Best Obituary/In Appreciation Story, beating out writers for The Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times. The Press Club's judges panel wrote, "Vivid storytelling about one of the most iconic women, combined with a punch."

Holly Gleason's writing always packs a punch, and we are so pleased to have a legendary music writer of her caliber among our family of contributors. If you didn't read this last year, we urge you to dive in today. And if you did, this piece does (to paraphrase the old rock-critic accolade) stand up to repeated readings.

—Chuck Reece

SIMPLY THE BEST

Tina Turner, a daughter of Nutbush, Tennessee, always knew what love had to do with it.

There was an oppressiveness to the heat in Miami during the dog days of summer. Heavy. Fetid. Airless. It was hard to draw breath, harder to exhale. Sweat didn’t roll off, it half dried and almost stuck to you.

Days like that, when nothing in the atmosphere seemed to move, you’d lay on the floor, or sit back propped against the couch grateful for linoleum. MTV was new, the videos gaudy and amateurish. But it was a distraction. Even if the rotation was so tight it seemed like the videos spun around every 90 minutes, it kept your mind off a heat that ice cubes only cured for a moment.

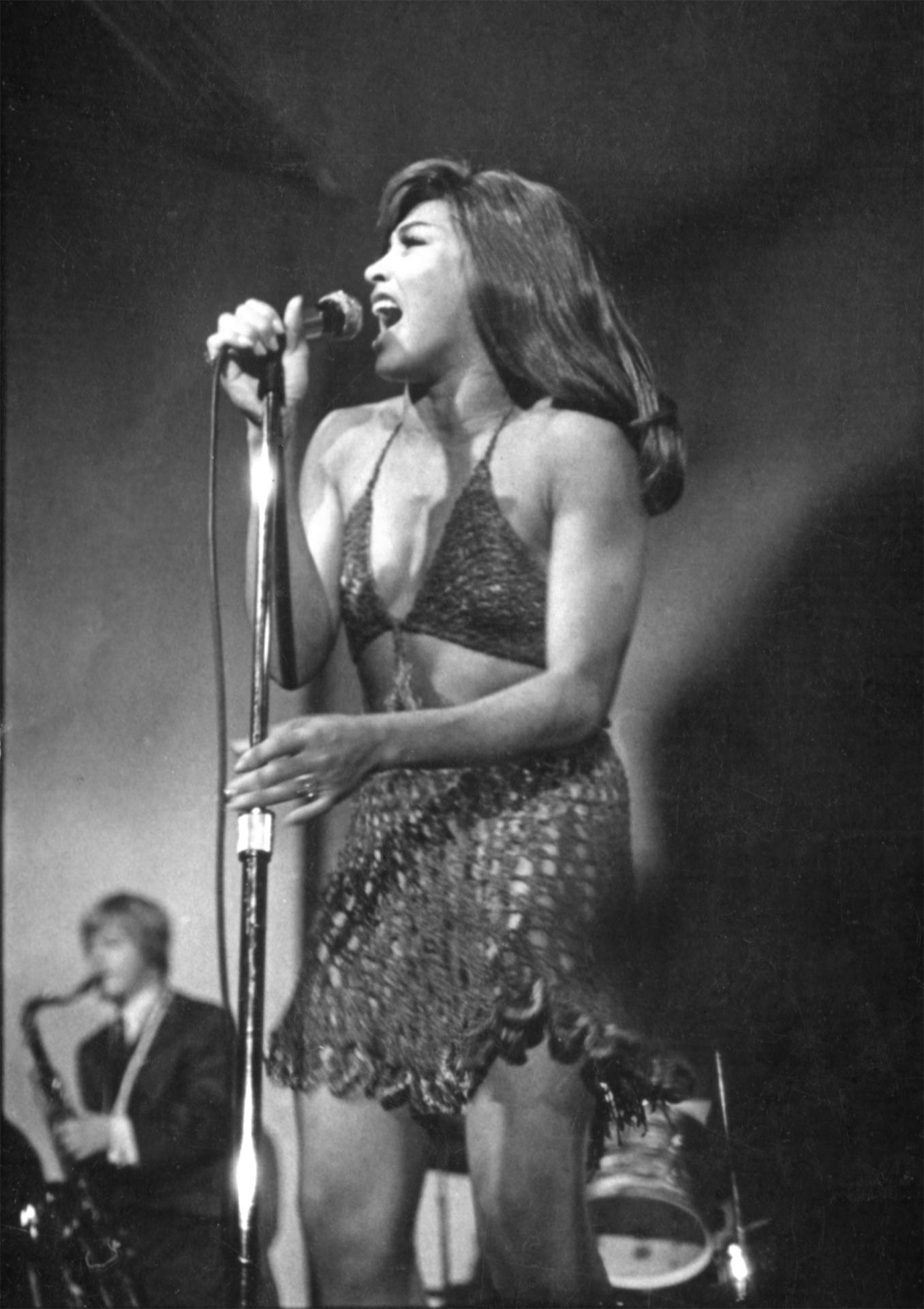

One day in 1982, there she was in a sequin top, Lycra pants, pineapple-frond hair everywhere, spike heels that were metaphorically and literally lethal weapons. Undulating and jiving, she tore through a grinding take on the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today).”

Feral. Visceral. Intense. Synth-drums whose ferocious intensity demanded attention. Casio-on-steroids keyboards blasting in a robotic machine drill, climbing the walls. Only with those coal-fire eyes and hips swaying back and forth, she had us from the blare of the horns and raspy smoke of a knowing alto bellowing from her lips.

TINA. TURNER!

“People moving out, people moving in / Why? Because of the color of their skin”

The clothes looked like they could’ve come from a Hialeah swap meet; the video “effects” looked like they came from local cable access. It didn’t matter. The clip sweltered, and the music churned. Above all, the Queen was doing what she did best: serving notice.

I smiled the first time I saw it. Jumped up and danced the second. Who didn’t wanna be a Turn-ette? C’mon! And if the hour was cooler, I’d jump into my first pair of heels and try to shimmy and strut along with the three women in the DIY clip.

Lotta kids at the University of Miami didn’t really know who she was. But to me, she was the ultimate Glamazon! Too young to truly know the Ike & Tina Revue, I was familiar only with the churlish “Proud Mary,” deep groove “Fool In Love,” and the slamming “Proud Mary” from babysitters and the horrible beatings and abuse she’d suffered from whispers, movie magazines and one oh-so-talked about PEOPLE interview. Even so, even then, I knew she was mighty and bodacious.

I remember her going step-for-step with Cher. Throwing down a number with the queen of sizzle Ann-Margret. And then there was her turn as the Acid Queen in the Who’s movie of their rock opera Tommy. While all my friends were terrified by the quaking, shaking goddess of LSD and everything forbidden, I was thrilled. TinaTinaTina! Those legs. That hair. Her little slip dress. And then there was the way she swallowed that song whole—and brought it down proper.

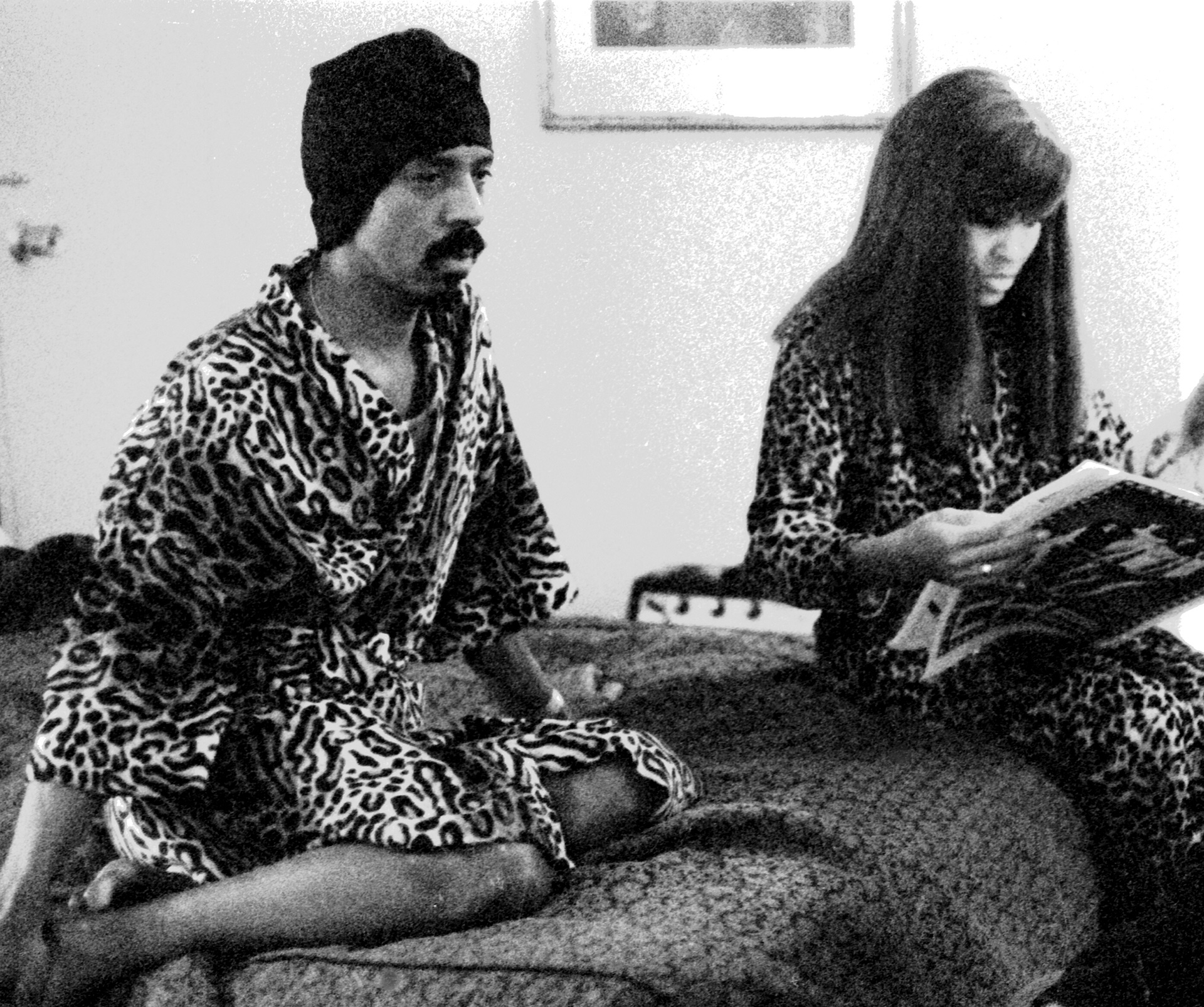

Whether you knew she fled the abusive Ike Turner, grabbing her purse and making a run for it, or whether you knew all she got was the kids and her name and a load of debt in the divorce, Tina Turner was righteous.

My Dad loved how she sang, how she danced—and probably how she looked. But he wasn’t coarse enough to talk about that with a daughter going to an all-girls school. Part of it was he was a gentleman; part of it, though, was she commanded a deep respect even then.

Whether you knew she fled the abusive Ike Turner, grabbing her purse and making a run for it, or whether you knew all she got was the kids and her name and a load of debt in the divorce, Tina Turner was righteous.

“Revolution, evolution, gun control, the sound of soul /shootin’ rockets to the moon, kids growin' up too soon / politicians sayin’ more taxes will solve everything / and the band played on”

She got by doing supper clubs in expensive hotels or any corporate gig where they could book her to sing “Proud Mary.” But she wasn’t just a survivor. She was a thriver. Whatever was coming her way, she was going to refuse to buckle and break.

Maybe it was that stubborn streak in a Southern woman from Nutbush, Tennessee. Maybe it was the way she threw her whole soul down the stairs of those songs. Maybe it was her will to blaze her own trail, then set the path on fire just to make sure people could see how hot she burned.

But what did this synth-y, blaring video mean? Where was she? What was she doing? Would there be more? Would someone spend more money to do her right? OMG! OMG! OMG!

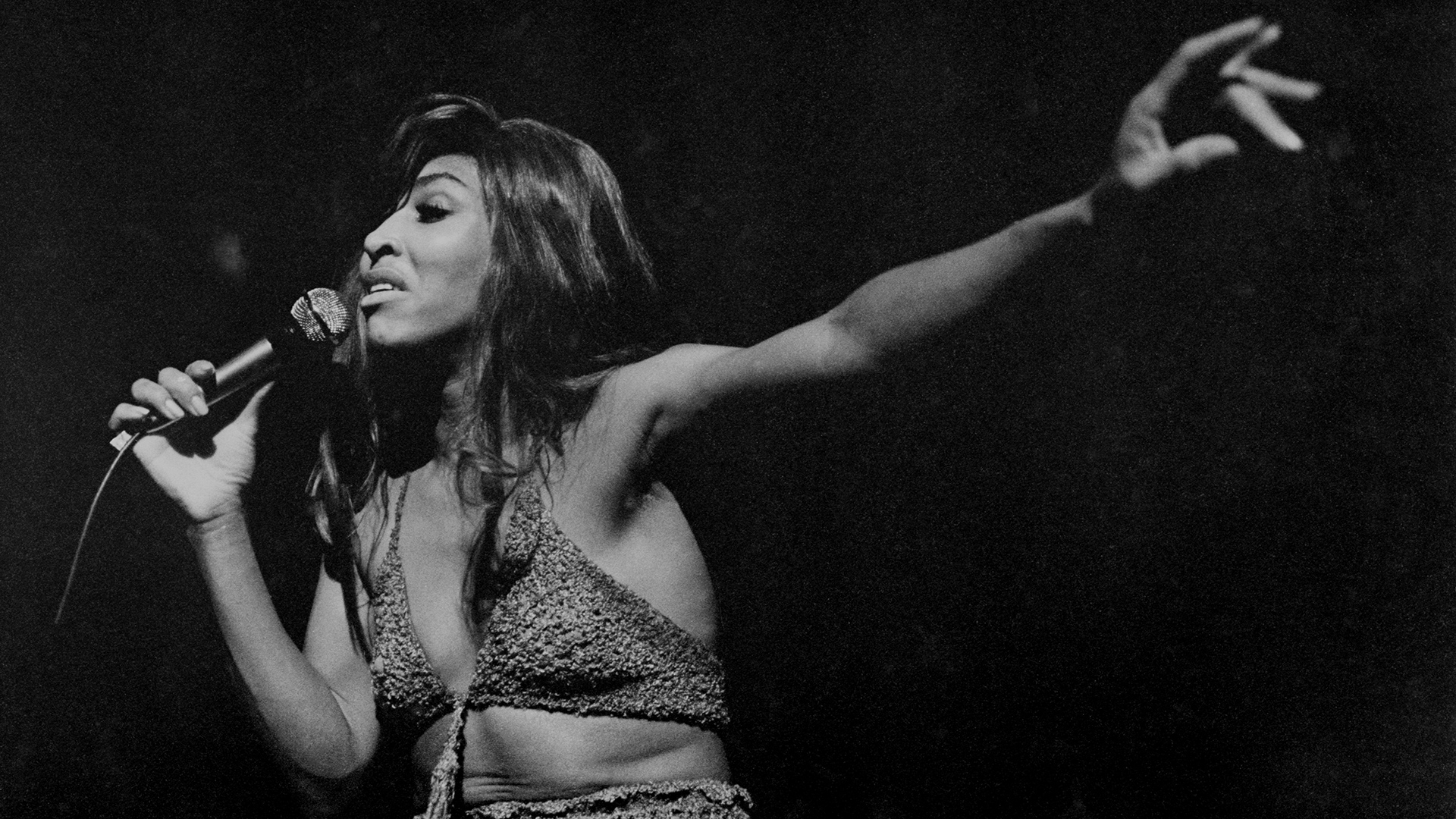

In a business that throws people away at thirty, she had to be somewhere in her—gasp!—forties. She was still shimmying, still sultry. When she moved, it was like a dry field catching a spark. Combustion was inevitable. You couldn’t turn away, and that torch in her voice was a blast that left you deliciously scorched.

The record exalted the tsunami talents in Turner’s full frontal vocal attack. When she leaned into the staccato stop/starts, the swivel turns, and groove pivots, she was precise, even lethal.

“Ball of confusion / that’s what the world is TODAY”

Miami vice. Racial tension. Escalating global conflicts. The oppressive heat.

Surely, hopefully, there would be more. And then in 1984, Private Dancer arrived. Savvy. Stark. Soul woven into the new wave/punk aesthetic. Even her cover of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” had a rock edge that proved she was swinging for the bleachers. If Mick Jagger learned to dance watching Turner when she and her ex-husband opened for the then-ascending Rolling Stones, she forged his rock ’n’ roll peacock swagger. No reason she couldn’t strut into the world of rock like she meant it, taking all the jagged pieces of who she was along for the ride.

Suddenly, there was a strong woman who wasn’t angry, wasn’t punching down. She was real and resolute, with zero shame and a willingness to engage from a place of actual honesty.

She delivered a haunted, austere, abrasive version of Ann Peebles’s “I Can’t Stand the Rain.” She laid down the law with “Better Be Good to Me,” from the hit-machine trio of Holly Knight, Nicky Chinn, and Mike Chapman. Turner wasn’t playing. This was grown-up stuff, rife with sexual promise and prowess, but also an obvious display of dignity.

Turner demanded respect because she’d been through it. She knew what it took to survive, to excel, to make Mama happy—and she was happy to draw that line.

Suddenly, there was a strong woman who wasn’t angry, wasn’t punching down. She was real and resolute, with zero shame and a willingness to engage from a place of actual honesty. When she approached Mark Knopfler’s “Private Dancer,” there were flames in her sotto voce delivery. She wouldn’t engage emotionally, but she would shimmy, turn, dip, and give the customer his money’s worth with complete, absolutely sangfroid detachment. For every baller who ever rolled into a strip club thinking they were all that, the jig was up. She laid the player out without batting an eye. Sucker, those girls ain’t looking at you, ain’t letting you in—they’re not even gonna call you by your name. All you are is a wallet, deutschemarks or dollars, an American Express card. And what we’ll deliver comes with no soul contact, just some flesh, flexibility, and an exhausted sigh.

BOOM! Balloon punctured, illusion splattered.

The emotional center of the album, though, was the raw silk of “What’s Love Got to Do With It.” Sexual brio without question, Turner owned the want, drilled into what animal attraction was without buying into the idea that romance was required. She knew.

“I’ve been taking on a new direction, taking on my own protection...”

Who needs to get hurt? Who needs a secondhand emotion that leaves you vulnerable, pained, betrayed? The song alone was gutting. Her performance was so wide open, but so fully in control.

The video, though, saw a tough, self-aware Turner en fuego. In a black leather miniskirt and denim jacket, she owns the streets of New York City. Walking in her signature stiletto pumps, she sings, turns, and smiles as she offers the calmest fierceness ever captured on film. So seemingly self-possessed, she was merely toying with the mortals who’d dare break her heart.

Another hero...

She was her own. Her Auntie Entity in Mad Max: Thunderdome was a future-world warrior, a role that let Turner’s super-ego emerge as a force in a major action picture. She more than held her own on screen with Mel Gibson; but it was the theme—literally “We Don’t Need Another Hero”—that spoke a robust truth to her reality.

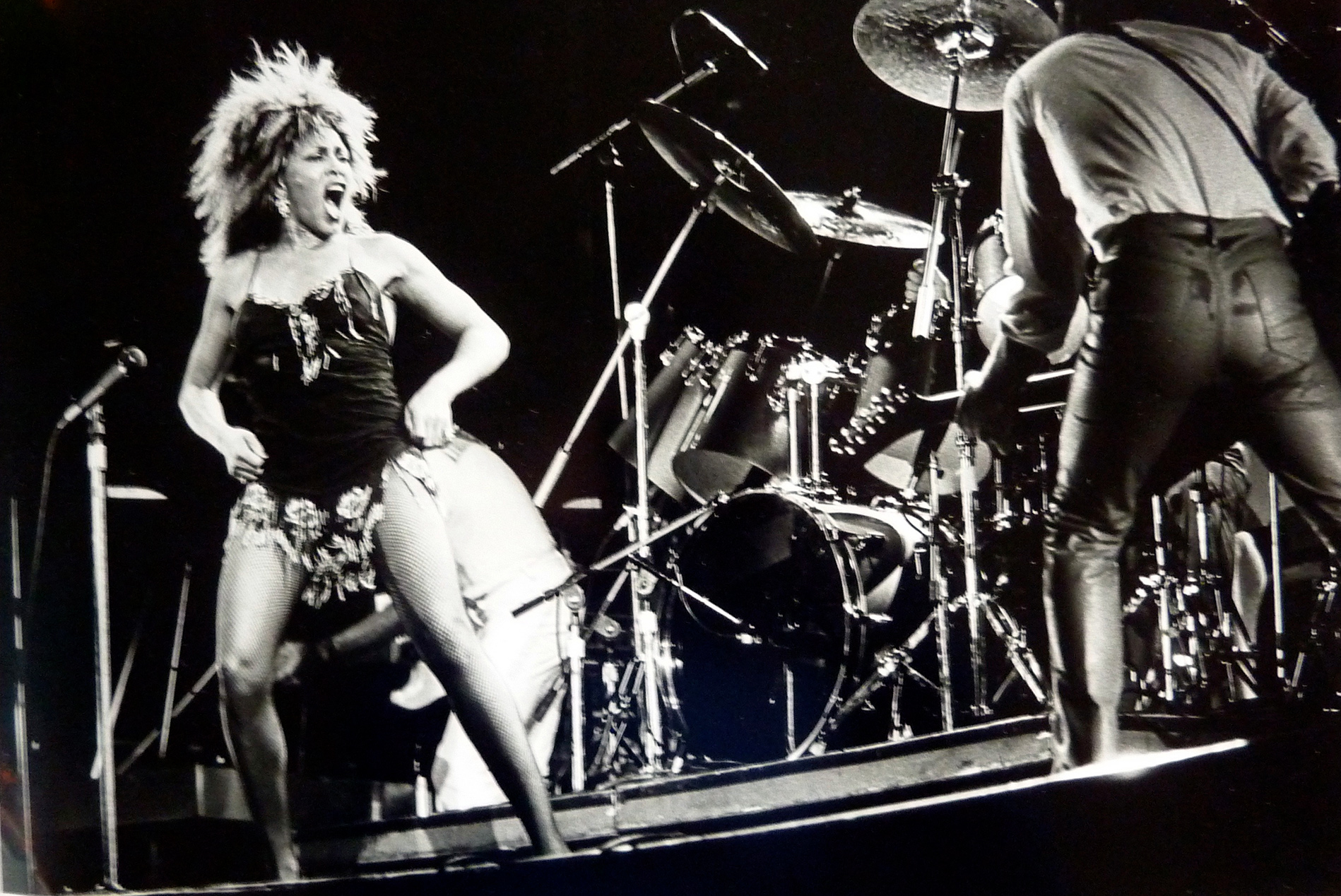

Tina Turner had arrived. Not groveling or begging, but with the elevation and elegance of a grand lady. She understood the struggle, but she recognized her power was transcending it. She would play arenas, sold out, packed in, with hydraulic lifts and her own romance novel-cover specimen playing sax. She would be the legs of a major pantyhose company. She would win six Grammys for Private Dancer alone, MTV awards, duet with David Bowie, Bryan Adams and have Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton play guitar for her.

Turner, though, had bigger dreams. Stadiums.

If women couldn’t—as people love to say—sell tickets, what could be more bodacious? If the Stones, the Police and David Bowie could, why couldn’t she? Harnessing the inner torque that gave the Phil Spector-produced “River Deep, Mountain High” such ballast, she drove her band, her intensity onstage and left it all out there; those songs she’d recorded giving women the power driving the momentum higher and higher...until she did.

No wonder the follow-up, in 1986, was called Break Every Rule. Those dates went on sale—in the U.S., Europe, the Far East, Australia—and those stadiums filled up. People knew. They felt it. They wanted that mix of old soul songs, modern rock, a bit of new wave pop. She would rise into the sky, dance like a teenager, owning her power and encouraging the crowds to sing along.

Foreign Affair, in 1989, upped the stakes, taking the erotica up several degrees with Tony Joe White’s overheating-to-the-melting-point “Steamy Windows.” When the Queen sang about getting down, it was funky, sanctified, an utter release. She exulted in all of it: your desire, her ability to ride the moment, what we all were seeking. It wasn’t just fire, but a thermonuclear meltdown in the back seat. Just when it blistered, she’d crack a window. Listeners would just shake their heads, knowing how good those moments of total innerquake could be. With more swerve than Barry White, she swooped through a make-out record for big kids.

Her look put the power back in the hands of the real women who worshipped her—and hooked all the men who could only fantasize about her.

Around that time, Turner showed up in Los Angeles at the scorched-wood-needing-a-paint-job Fred Sands Building. It was a dump on Van Nuys Boulevard in very nondescript Sherman Oaks, but the rent was cheap enough for little HITS magazine to be based out of two floors. I was a young writer working there when she suddenly appeared in our basement office. Wearing a gorgeous crepe Richard Tyler suit—of a mauve camel shade that defied description—with a luxurious, matching silk blouse, she was redolent of sophistication. Yet she beamed and asked us young rock refugees about what we did, where we were from, what we were listening to.

She always delivered, always came hard—and looked smashing good doing it. No one rocked a silvery Versace slip dress with black lace like Turner. Or the chain mail dress she back bent in to defy gravity and age for another shoot. Or the leather pedal pushers and bustier. Even a white shirt tied up with basic blue jeans. Whew! Just whew!

Ironic iconic. The common transformed. Her look put the power back in the hands of the real women who worshipped her—and hooked all the men who could only fantasize about her.

Foreign Affair, with its “Undercover Agent of the Blues,” “Be Tender With Me Baby,” and “Ask Me How I Feel,” delivered complicated emotions. These were adult entanglements, loves that won’t quit, pain that cuts deep and pairings that expect fealty. It opened up a plain that suggested rock & roll could be more than what the hair metal bands were serving.

Foreign Affair also delivered “The Best.” If “Better Be Good” and “What’s Love” were signature songs, “The Best” created a vortex that was the ultimate invitation, a revelatory place where sex and love converge.

Turner was breaking ground. Creating space for adults to be adults. Owning her want. Rejecting the dismissal of ageism, sexism, misogyny, racism, and musical boundaries. She might have come from the chitlin’ circuit, but she’d conquered the world’s rock palaces, delivering a kind of sexual franca that captured our imagination—and hormones.

Inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in as part of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue in 1991, it would take three more decades for her to be inducted on her own. When Angela Bassett, who had been nominated for an Academy Award for her portrayal of Turner in the 1993 biopic What’s Love Got to Do With It, walked onstage at the 2021 induction ceremony in Cleveland, the crowd lost its collective mind. It wasn’t the presence of a movie star, but the way Bassett honored the grit of how Turner had lived her life. Her induction speech invoked all that, too; it was a witness to Turner’s strength and the glory of her talent.

I was crammed at a table as far back on the floor as you could be, mesmerized. Eighteen years earlier, Bassett’s performance in the movie, chanting as Turner embraces Buddhism, had rung through my body in the theater. As a keyed up, go-go-go kind of girl, meditation is hard for me. But watching Bassett-as-Turner intone the basic sacred Buddhist words, it seemed so simple. Like speaking in tongues, it’s how the tones move through your body, setting vibrations off in your bones and your flesh that reach beyond the conscious mind.

For all the emotion that came through the notes she sang, the colors she gave them and the way she carved the lines to her own sense, she understood the divine was as sublime as the most primitive hunger. Somewhere between those two was the exalted now: a place where our mortal coils could find what we were looking for.

Poking around the internet, I’d found the recordings Turner had made of her chanting. On nights when it was all too much, I would play those recordings. Sometimes with my feet up the wall, sometimes in Lotus position, occasionally flat on my back in corpse pose. It never failed to unwind whatever had knotted inside, sometimes dropping me into a sleep that came in soft blackness.

That was the magic of Tina Turner. For all the emotion that came through the notes she sang, the colors she gave them and the way she carved the lines to her own sense, she understood that the divine was as sublime as the most primitive hunger. Somewhere between those two was the exalted now: a place where our mortal coils could find what we were looking for.

For Turner, it was a European record executive who picked her up at an airport amid an exhausting promo tour. Erwin Bach, 16 years younger, would be her paramour for 27 years, husband for 10; when Turner’s health imploded, he gave her one of his own kidneys to keep the woman he loved alive.

More than happily ever after, the strength she imbued so many with, the reality she created, this great love answered the question posited in her breakout hit. Her happiness and solidity with Bach was the perfect manifestation of what love had to do it with it.

Somewhere, she’s already stars flung across the heaven. She is soul and fury, music and delight. Looking down, the woman who’d deliver “A Change Is Gonna Come” in concert with a Sunday morning conviction wants us all to figure it out. Love. Respect. Dignity. Compassion.

Amen.