The Only Lie

Her father was a Pentecostal minister who never told a lie in his life. Until he did. And it was so big, it stayed with the family forever.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is true, with one exception. The name of the wealthy Arkansas family has been changed.

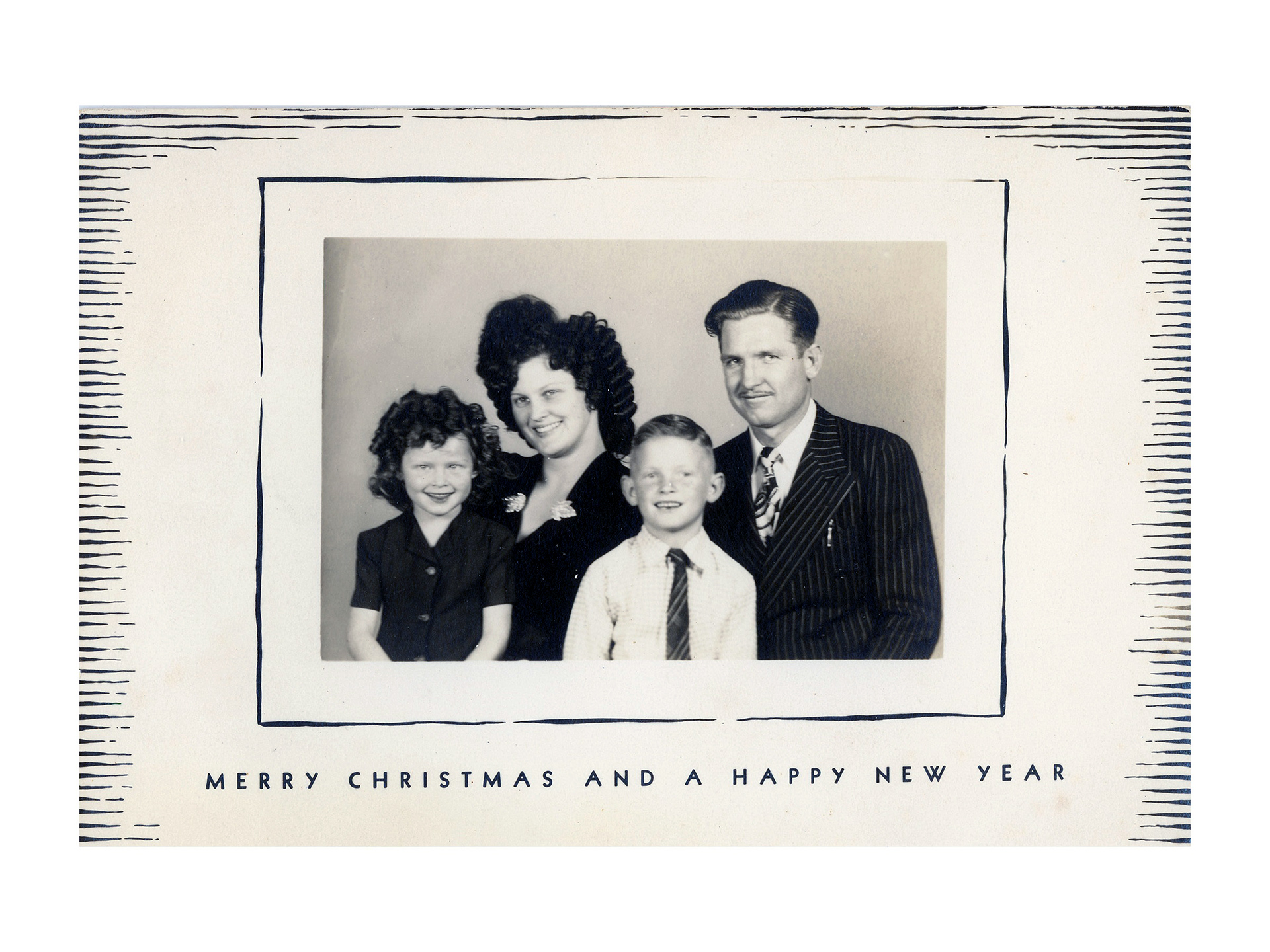

The worst part about the secret we kept is that because of it, one person’s entire life was allowed to disappear, swept back into a corner where memory eventually fades, as if by not speaking the name, the deed could be erased. I was eleven years old then and my brother was thirteen. Decades later, we still wondered how things might have turned out if everyone had known the truth.

When Beau Hilliard walked into the Pentecostal church on the corner in 1952, following the music that sounded for all the world to him like boogie-woogie, everyone assumed he was drawn to the young and beautiful piano player. A Baptist in a Pentecostal pew in this small town would be noticed, and Beau was a Baptist. But he was also one of the Arkansas Hilliards, and gossip flowed immediately out the front doors and within minutes after Sunday morning worship, it would trickle into every house.

Sister Coker inclined her head toward the back row and whispered to me, “Nita Faye, what’s he doin’ here?”

I had already given up trying to figure out how certain churchwomen, without seeming to turn around, could keep track of every movement in the building. I had to twist myself completely around in our pew to see the back row and report.

“I don’t know him.”

Sister Thigpen leaned across my lap to respond to Sister Coker.

“It’s because of her.”

She referred to my unusual mother, who at that moment was playing the piano up front, a version of “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” that the good people of that congregation hadn’t heard before. Mother, although she was the preacher’s wife, was only recently removed from her own honky-tonk Saturday nights. On this Sunday morning, she was still trying—without much success—to tone it down a bit.

The first time our family laid eyes on Beau Hilliard was when he slid into the back row that Sunday and sat there bobbing his head to the beat and smiling and shouting “A-man!” when everybody else did. Since I’d never been in any other kind of church but Pentecostal, I assumed then that maybe Baptists hollered out loud the way we did.

Beau was a beautiful man, every bit as tall as Daddy, with a full head of slicked back hair. Everybody said Daddy was good-looking, but Beau was all that and then some.

Beau was a beautiful man, every bit as tall as Daddy, with a full head of slicked back hair. Everybody said Daddy was good-looking, but Beau was all that and then some. He’d have been a head-turner even if he was poor, but there was all that Hilliard money.

The Arkansas Hilliards were a quiet dynasty, unlike the rowdy, political Longs of Louisiana and the oil-rich Cullens and Murchesons and Hunts of Texas. They wouldn’t stand out in that crowd, but when you got hold of a list of their holdings, it was staggering how much of the state was owned by this one family.

The Hilliards’ pastor would know by afternoon why their youngest son was not in his customary seat at his own church. He’d have heard that Beau stayed all the way through one of Daddy’s fire-and-brimstone sermons and even put money in the offering plate.

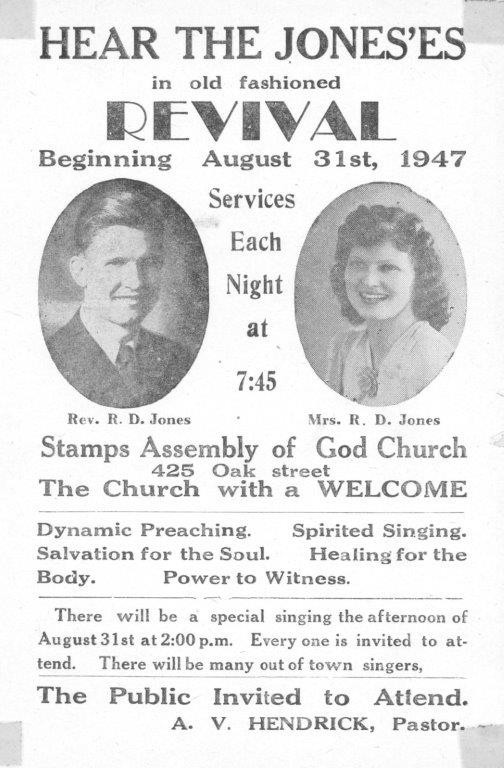

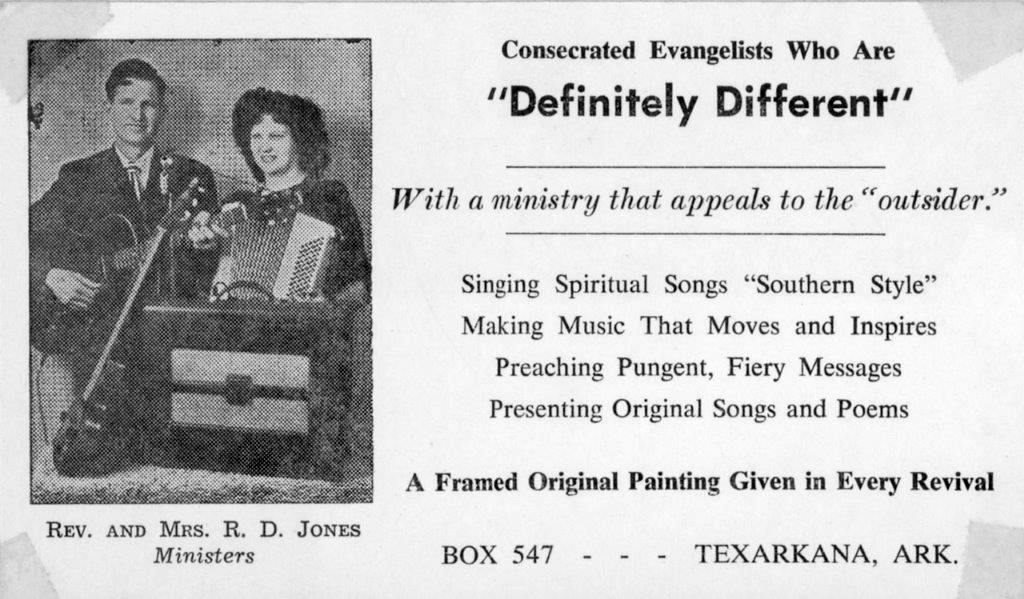

You didn’t need to be churchy to see what had happened since my parents, Brother Ray and Sister Fern Jones, brought their music to town. People came from all over to our once-a-month singings, a Southern Gospel tradition.

Music was also the reason the church swelled to overflowing during any holy event. We raised the roof at every opportunity, so if you believed in Jesus, or possibly even if you didn’t, when it came time to celebrate his birth or grieve over the crucifixion or exalt over the resurrection, you’d want to be with the Pentecostals.

At Easter time, people seldom sat down. Daddy opened the service, shouting out, “Hallelujah! The stone is rolled away!” And then he didn’t say another word for about an hour while we sang. A trumpet player from a nearby dance band played a magnificent opening that started us off with “Up From the Grave He Arose!” and we stood through all the verses of “He Lives!”

Beau was a music lover who played piano a little, and after a bit of head-turning to gawk at one of the richest men in town, people said, well, of course it’s natural that he’d come to hear Sister Fern’s gospel style. We were wrong. It wasn’t Mother that Beau ended up spending so much time with. It was Daddy.

Beau began stopping by the parsonage a couple of times a week and then every day and then twice a day. He announced himself that first time, rapping his knuckles on the wooden frame of the old screen door, followed by a tentative greeting.

“Reverend Jones?”

Daddy was at the stove. He went to the back porch with a spatula in his hand to retrieve our guest.

“Brother Hilliard? Come on in.”

Beau stayed for supper and he just kept coming back.

First there was the tap, tap, tap and then, “Brother Ray?”

Someone always had a crush on one or the other of our parents, but my mother, Fern, was monumentally secure in her position as Raymond’s Big Ol’ Doll Baby.

Soon it was tap, tap, tap, “Raymond? You home?”

It was the first time I heard anyone other than family call Daddy by his given name. Everyone else we encountered in churches and revival tents and on the radio called him Reverend Jones or Brother Ray. Even the non-believers at the barbershop called him “Rev.”

It was Daddy who stirred the pots in our kitchen to feed our family and it was Daddy who said to anyone stopping by, “Take some dinner with us?” or “Stay for supper. There’s plenty.”

It might only be vegetable soup made from whatever was growing in the garden out back, because nobody in the congregation had butchered lately and there wasn’t any meat except a small chunk of dry-salt left to season tomorrow’s beans, but we always had a skillet of cornbread or biscuits from the two pans we made at breakfast, enough to last the rest of the day. It was plain, but there was always enough for Beau.

This friendship with a member of another church put Daddy in an awkward position. It was stickier because of how rich Beau was. People who didn’t know the constraints of our sect’s rules for pastors might have assumed our family would profit from spending so much time with a Hilliard.

If anybody had asked, my brother and I could have told them different. Daddy’s church believed a pastor’s family must “live by faith,” trusting in the small salary and the ten percent tithes of goods and services from members. No prosperous person would hand us a bunch of cash to buy new shoes for school or a new dress for Mother. We made do with what our church members provided and nothing more.

Though Mother was often at home when Beau knocked, she paid him no mind because she didn’t have to. It was only Beau. She preferred to play the piano or her guitar, knowing somebody else would let him in, and if nobody else was home, well then, he could come back later.

She wasn’t singling out Beau to ignore. She was unwilling to commit to small talk with any member of any congregation. She was busy preparing for the future. She passed her time with her music and painting and designing and sewing the clothes she sketched and working on writing a hit song so it would play on the radio and sell lots of records and make us rich.

Nor did she mind the relationship that grew between Daddy and his new follower. Someone always had a crush on one or the other of our parents, and she was monumentally secure in her position as Raymond’s Big Ol’ Doll Baby.

If my brother and I were home but Daddy wasn’t, we let Beau in. Beau said he’d be fine sitting at the table. He’d turn on the radio and bide his time. The rule about a man not calling at the parsonage without the Reverend present was bent to fit Beau. We let him in anyway.

I came out of my room just to see what he was wearing. Nobody had clothes like Beau. They weren’t even in the catalogs Mother saved. Daddy liked to look good, and he did his best with what he had. People watched him no matter what he wore, but never in his life had he owned a pair of pleated slacks that draped and fit just so, the way Beau’s did. Daddy took pride in keeping his dress shirts crisp, the way preachers do, but his off-duty wardrobe was sparse. Beau, on the other hand, had soft, perfectly fitted shirts just for everyday.

Daddy wore dark brown or oxblood wingtip shoes, and so did Beau, but his had the gleam of leather too good for Daddy to afford. Beau’s wardrobe made him look like he was in charge of something, but that was never the case during the time we knew him.

Daddy tried to be subtle about checking his own reflection, but we could tell he was proud of his hair. The ways he tended to his pompadour were graceful, balletic almost, with a tug of a lock from the Brylcreemed mass onto his forehead while the rest of the hair was pushed up and back and patted once in confirmation he was groomed for maximum effect. Beau took to copying Daddy, messing with his own hair all the time, but we didn’t laugh in front of him because it was a bit sad, his determination to duplicate every little habit of his new friend.

Even Mother was sensitive to whatever it was Beau was seeking. I heard her to say to Gramma K on the phone that she thought Beau was the loneliest man she’d ever seen.

Beau spent much of his time at our kitchen table, which was the actual and spiritual center of our house, while the spacious home he owned a few blocks away offered a larger, empty kitchen with a table by a big window where curtains floated in and out all day long, borne on a breeze that never quite reached all the way into our much smaller rooms.

Sometimes it seemed there was nowhere else that Beau needed to be, but Daddy didn’t have much leisure time. He conducted several church services every week and officiated at weddings and funerals and baptisms, and he was also raising two kids and working in the garden and getting his sermons ready and calling on the sick. When he got a few minutes to himself, he went fishing.

Beau went everywhere he could with Daddy. Beau learned to fish, he learned about growing vegetables, and even going to the gas station became a job for two men. Watching him acting like a kid, though he was only ten years younger than Daddy, seeing him soak up everything Daddy had time to teach him, I wondered why he never learned how to do anything from his own Daddy.

I’ll tell you who didn’t mind a bit. My brother. With Beau around, Leslie Ray took the opportunity to disappear, even if all he could think of to do with his freedom was to play the kind of music he liked on the radio in his room. As long as Daddy called him to grab his fishing pole when it was time to go to the lake, he tolerated Beau’s company just fine.

The Hilliards didn’t live in showy mansions, but they did prefer big white houses scattered all over the state. As each Hilliard got married, one of their gifts from their parents was a white house that looked like all the others, like a wedding cake with a hundred windows. As each of them paired up, Old Man Hilliard put them in charge of one of the family’s companies.

They asked if he’d stop by and see them, and off he’d go to the biggest house in town, where he prayed with them and had many glasses of sweet tea with them, or so he told Mother when she asked, “What’d they want with you this time?”

Beau had taken Velda as his wife just before we met him. Besides the white house, the family gave the newlyweds acres of land outside of town, with a working dairy farm. It was said they received that extra gift because Old Man Hilliard liked Velda best of all the boys’ wives.

Velda stayed out at their farm most of the time, building and planning and breeding prize livestock and toting up profits in all her endeavors, the way a Hilliard was expected to. The woman Beau married was turning herself into the person his family had hoped he would be. The family hadn’t yet found exactly the right fit for Beau within the company, and he was holding his breath for fear they’d send him off to do something he’d hate.

Having fulfilled the marriage part of his duty, Beau was temporarily free to spend his days knocking around while people wondered who he would be or what he would be or if he’d ever amount to a hill of beans.

Not long after Beau started coming over, Daddy began receiving phone calls from Old Man Hilliard and Mrs. Hilliard. They asked if he’d stop by and see them, and off he’d go to the biggest house in town, where he prayed with them and had many glasses of sweet tea with them, or so he told Mother when she asked, “What’d they want with you this time?”

When Daddy called on the senior Hilliards, Beau stayed home, and Daddy teased him about it.

“Hey Beau, I got a message right here, says some folks are in need of prayer. Lemme see here….” Daddy would glance at a piece of paper as if reminding himself where he was headed next. “Name of Hilliard. Why don’t you pull the car around and let’s go see them?”

“No thanks, Raymond. I got some chores to do for Velda today.”

Both men found this endlessly amusing, the young heir squirming out of a midweek visit with his own parents. The rest of us found it interesting the Hilliards were all the time asking the young Pentecostal preacher to pray with them, instead of their own pastor.

When Beau’s presence was requested at a Hilliard company business meeting, he was unhappy about it for days before, and then he got dressed up and drove himself to Little Rock in his big Cadillac. He never said much about what went on over there, and he wouldn’t likely have paid close attention, anyway. Beau had trouble sitting still.

Gramma K came from California to visit, and one night after Beau went home, she said, “That boy’s all wound up. That’s not good.”

I found myself sort of sticking up for him.

“He’s kinda nervous sometimes. Not all the time, though.”

It’s true that Beau was high strung now and then, but so was our mother. In fact, Gramma herself said the same thing about her own daughter. Gramma had a theory about high-strung people.

“You stay wound up like that for too long and it’ll give you a permanent nervous condition.”

A “nervous condition” was her euphemism for crazy.

When I asked Daddy if he thought Beau was developing a permanent nervous condition, he said, “Beau’s gonna be all right.” He wanted to know where I got such a notion and when I told him from Gramma, he laughed.

“She said that? Naw, she’s wrong. Beau’s all right.”

Daddy took a nap every Sunday afternoon and our town’s phone operator knew that, so she wouldn’t ring the house until just before time for him to go pick up folks who needed a ride to the Sunday night service. It was customary for the preacher and sometimes another car driven by a deacon to head out to pick up people who didn’t drive. A preacher never drove people in his car without another person present, so I went along sometimes, or Leslie Ray went, or Beau.

That Sunday night, Leslie Ray and I walked to church at the appointed time. Mother stayed behind. Daddy and Beau hadn’t come back yet from picking up folks. While everyone in church waited, Mother came in through the side door and walked to the pulpit. She said Daddy—“Reverend Jones,” she said to the congregation—had called her and asked her to lead us all in prayer for some church members who were in distress. Daddy asked her to tell the congregation he would be staying with these people for a while, and we should all keep praying.

Then Mother left. She went out the door and didn’t come back. The rest of us sat there for a while, wondering what to do next, and after a while, we all drifted out.

My brother and I had just gotten back to the parsonage when Daddy came in. Mother hugged him and went over to the stove and started making coffee. A second later, Beau was right behind him, and he sat down at the table.

“You kids go on now,” Daddy said. Leslie Ray and I didn’t make any pretense of moving past the door into the hallway. We stayed there to watch and listen.

“Sonny Joe was hit,” Daddy said to Mother. “The car hit him.”

“What car?” she asked.

“Our car.”

The story came out gradually, with the two men imparting only the most essential facts and nothing more, squeezing out the truth of what had happened late that Sunday afternoon in measured amounts, so that it later seemed only a person who had to know could ever piece the whole together.

Pacing wasn’t something Daddy did very often, but he began moving around, back and forth over the linoleum where many other preachers and their families had worn a pattern around the table.

“Sonny Joe was hit,” Daddy said to Mother. “The car hit him.”

“What car?” she asked.

“Our car.”

“Is he hurt?”

The silence was a second too long.

“Raymond—is he hurt bad?”

“He’s gone.”

“Gone?”

“Sonny Joe has passed away.”

She covered up her mouth the way she did when she got one of her sick headaches and was on her way to the bathroom.

The picture that came to mind was too horrible to hold on to.

I knew Sonny Joe. He was five years old. I knew his mother. Daddy had me fill in as a Sunday School teacher sometimes, which was how I came to know the little boy, because his mother sent him to church even though she didn’t come often herself. He loved Bible stories, and I could embroider enough details around Jonah getting swallowed by a whale and Noah building an ark to keep squirmy kids occupied for a while.

Sonny Joe lived with his mother at the motor court on the other side of town. There was another child, a baby girl, and no daddy in sight.

It wasn’t unusual to send a child to church with someone else. What with Sunday School classes, ice cream socials, church suppers and picnics and church people helping raise each other’s kids, a whole life could be built around church.

Daddy went on his regular rounds, picking up people to bring them to church, picking up this woman’s boy because she wanted the church to take care of him, and now on this one night, everything in her world and ours had changed.

“We didn’t see him,” Daddy said. “We were slowing down, fixin’ to park in front of the motor court and go get him. He jumped out. Right in front of the car.”

It was quiet again .Nobody asked anything. A simple question like, “And then what happened?” seemed wrong, because this was a real boy we were talking about, a boy we all knew, and not some story in a book.

Where was the car that killed Sonny Joe? Was it our green Pontiac parked out in front right now? After you hit somebody with your car, did you just drive it home?

I pictured the road that ran by the motor court. Sometimes Sonny Joe waited inside, but other times his mother let him stand out front, watching for the preacher’s car.

Beau was silent. His face was still. He stared straight ahead at the kitchen wall. Of course, he must be shocked. He saw the whole thing.

Mother’s words started, then stopped, then began again.

“Where is he now?” she finally asked.

“Over at Latimer’s,” Daddy said. Our local funeral parlor. “His mother wants to stay with him. She’s got that baby girl with her, and I told her I’ll be over there in a little while to sit up with her.”

He knew I was standing nearby.

“Nita Faye, I’m gonna bring the baby back here. They got no kin anywhere close enough to help. You watch the little girl for me, you hear?”

“Yessir, I will.”

Our people treated the ones who departed in very specific ways. We sat up all night with them and kept them company during all the stages of their crossing-over. We prayed over them every step of the way to ensure a peaceful passage over the River Jordan to the Other Side .

“You coming?” Daddy asked Mother.

A preacher’s wife normally might go along to comfort the grieving mother at the funeral home. But Daddy didn’t really expect Mother to answer. Anyone who knew our family also knew the story of Mother and her dead babies, that she and Daddy had buried two of their own and it was agreed that Mother hadn’t been the same since.

“You know what my Daddy will say? He’ll say, ‘I’m not surprised.’ He’ll say, ‘I don’t know why the Lord saw fit to put breath in that boy of mine.’”

No, he wouldn’t put her through that, staying with a young mother, waiting for a son to be prepared for viewing. Maybe Daddy brought it up because of Beau sitting there. Daddy was always on duty, and he would certainly observe all the rituals church folks expected.

“Oh Raymond, honey, I don’t believe I can go,” Mother said. “I just can’t.”

“I’ll pay for everything.” Beau said. “Get that boy the best casket.”

Daddy was eager to move to another topic.

“We’ll talk about that later. Right now, we need to go get that baby.”

“I’ll take care of the family. Whatever they need,” Beau insisted. He asked Daddy, “How much should I give them? To start with?”

“Well now, Beau, that’s...”

“It’s the least I can do.”

“We’ll talk about that after a while,” Daddy said. “We’ll take up a collection at church to pay Latimer’s. Lord knows those people don’t have a thing.”

Daddy finally stopped moving. He turned around and looked Beau right in the face for the first time since they’d come in, and that’s when Beau fell apart.

“I didn’t see him, Raymond.” Beau sobbed. “He just darted out from between those cars. Ran right out in front...”

Daddy sat down at the table.

“It wasn’t your fault. I didn’t see him neither. Don’t you think if I’d-a seen him, I’d-a said something? If it was me driving, it would have happened to me same’s it did to you.”

“No, it’s my fault. Maybe I was going too fast.”

It wasn’t the right time to feel relief, but that’s exactly what I felt. Daddy didn’t kill Sonny Joe. He wasn’t driving. Beau was.

But now Beau, poor Beau.

“You were slowing down,” Daddy said. “You hear me? It wasn’t your fault.”

“You know what my Daddy will say?” Beau replied. “He’ll say, ‘I’m not surprised.’ He’ll say, ‘I don’t know why the Lord saw fit to put breath in that boy of mine.’”

What Daddy was proposing, if I understood him right, what he was saying was...

“Listen here, Beau. Little Sonny Joe, God rest his soul, he was the only person on the road. Let’s just leave this between you and me.”

And there it was—the only time I knew Rev. Raymond Jones to tell a lie. Oh, we knew it was a lie. Everyone in that room knew omission was the same as a lie. Daddy said so to us kids. He said it often in his sermons. He was a man of absolutes. There was no gray area in his code of conduct, and if you didn’t want to take his word for how a person ought to do, he’d quote you chapter and verse from the Bible to back it up.

We never asked Daddy whether he and Beau were questioned that night about who was driving. His lie of omission was already a shock as big as Sonny Joe’s death. In those times, in that town in the 1950s, preachers were respected. Daddy was especially popular. He was president of the local ministerial alliance. He and Mother drove to Little Rock on Saturdays to sing on the radio. A thing like that mattered back then.

Mother and Beau drank coffee while Daddy dipped his tea bag up and down in the mug of hot water she put in front of him. I went into my room and pushed the bed up against the wall so a little girl could sleep there with me. Last time I saw Sonny Joe’s sister, she was taking her first steps, and I worried she might try to climb out of bed.

The baby girl was the opposite of her brother. Though I’d seen Sonny Joe sample from every table at church suppers, he always looked like he needed another meal. This one was a wiggly, round bunch of dimples who didn’t want to settle. She looked at everything in my bedroom, pointer finger extended, laughing and babbling sounds that were almost words. She pointed at my doll on the chest of drawers. I got up from the bed and handed it to her. She poked its eyes, nose, and mouth. She poked at my eyes, nose, and mouth. Then clutched my doll tight and finally went to sleep.

I heard Beau and Daddy leave. They went to spend the rest of the night with Sonny Joe’s mother, talking and praying and making funeral arrangements. All of that would be accomplished before Daddy would finally come home.

Next morning before dawn, the baby was still asleep in my bed, and I found Daddy sitting at the table with his Bible and his note pad, the same as he did every morning of his life. He hadn’t been to sleep.

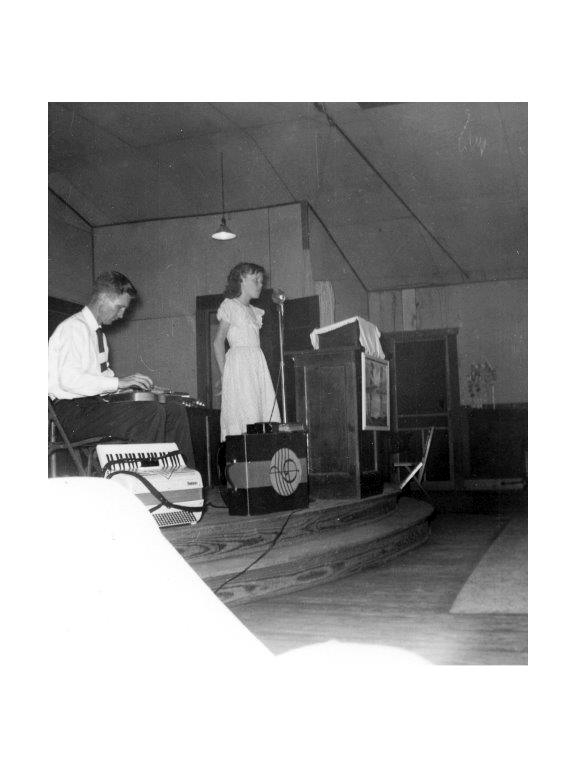

“Nita Faye, Sonny Joe’s mother wants you to sing at his funeral.”

I shook my head no. I’d been singing at funerals for just a little while. Daddy believed there were milestones in the life of a preacher’s girl who was being raised to serve the Lord, and he had determined that I should use my voice in the ministry. Still, I had only sung at the funerals of old people. It felt horribly wrong, too much to ask, that I should stand up there and sing a song for a young boy. I said no, I don’t want to.

Daddy wouldn’t yield. He said, yes, it was necessary. He reminded me he couldn’t ask Mother to sing for a child, not after all she’d been through.

I hadn’t known those babies, my brother and sister, since both of them died when I was much younger, but our people talked about them often, with a great deal of head-shaking and murmuring over the particulars. Years after their passing, when Mother’s scrapbooks with pictures of our babies were opened, handkerchiefs came out and tears flowed, and eventually there would be coffee and sometimes a little cobbler to go along. Death and grief and food, strong coffee and sweet tea were all part of the cycle.

And so, when this boy was laid to rest, the cycle would begin again and the women of the church, if Sonny Joe’s mother would allow it, would weave stories of his short life into their other grief stories and his name would carry forward within that body of believers whenever they talked about birth and death.

The afternoon of the funeral turned off much hotter than expected. Daddy propped open the double doors to get some air moving inside, and to allow the men from Latimer’s to carry Sonny Joe’s coffin down the center aisle and position it in front of the altar, where floral arrangements were waiting.

That afternoon, I didn’t want to be a servant of the Lord. I was a person who had just completed the fifth grade at school, who had once told exaggerated stories to Sonny Joe to make him laugh.

When Daddy turned on the ceiling fans, the mixture of hot air and the smell of flowers and the light pouring through the double doors slapped me in the face. Flowers inside a church signified a workday for our family. We were the officiants at these rituals, and we buried whatever emotions we carried into the building. We had to honor a congregant.

That afternoon, I didn’t want to be a servant of the Lord. I was a person who had just completed the fifth grade at school, who had once told exaggerated stories to Sonny Joe to make him laugh, had watched him tilt as far back as gravity allowed in one of the small, painted chairs in the Sunday School room, asking impertinent questions that showed his intelligence and high spirits.

On the platform behind the altar, I propped up the words to my song on a music stand and moved it over next to the straight-back chair where Daddy’s guitar leaned so I could practice with him.

A shadow filled the doorway. A slender man removed a panama hat and moved quietly to sit in the last pew.

I squinted against the sunlight.

He put his hat on the seat beside him instead of hanging it on the hat rack like other men did. Even Daddy, a frequent wearer of fashionable hats, hung his up in the back on one of the pegs. Putting a hat on the pew beside you separated you from anybody who might sit too close. The church, however, was still empty.

“Hey Beau,” I said. “You’re early.”

“Hey Nita Faye. Just felt like settin’ here.”

Daddy began adjusting things near the pulpit. He said nothing to Beau, but gave me instructions, as if this was just another church function.

“Nita Faye, go put some more fans on the seats. In the back. I b’lieve we’ll need them.”

I took the box of paper fans on sticks that Latimer’s Funeral Parlor provided for every church in town and wandered up and down the row of pews, adding enough fans for a crowd.

When I got to Beau, I handed him one. He took it and didn’t say anything else. Daddy wasn’t talking to Beau, and I felt put upon that both of them were allowed to be distant when I also wanted to remove myself. I wanted to not have to sing at a little boy’s funeral while my Mother, the preacher’s wife, who should have been doing this, was in the bedroom at home, and by the time we all got back there, she would have one of her headaches that would last for days.

Daddy called me back to the platform.

“Let’s go over your song.”

I started off so he could find the key. He strummed a brief intro, and I began with the first few bars of “Beautiful Isle of Somewhere.”

Daddy stopped playing. “I don’t know that one well enough,” he said. “You better sing it by yourself.”

Sing this song at a funeral with no accompaniment? This really was unfair. Daddy was a perfectly fine guitar player. He and mother had both played all their lives. He could at least strum something now and then to give me a little backing.

“I don’t want to sing it by myself.”

“Well, you’re gonna have to.”

At least Mother could have shown up to play piano. I thought it, so I said it out loud.

“Why can’t Mother...?”

“You know your mama can’t...”

“Just to start me off...”

“You hush now. I said hush.”

The church filled and people milled around in the doorway, spilling outside into the summer sun. People from other churches and people who never went to church turned out to honor a child most of them didn’t know.

I began to sing into the stifling heat.

Somewhere the sun is shining,

Somewhere the songbirds dwell,

Hush then thy sad repining

God lives and all is well.

A moan came from the back and then another one from somewhere else in the pews and then loud sobs from Sonny Joe’s mother. She was right in front of me, but she didn’t look at me. She looked only at her little boy, whose open casket the funeral people had elevated so that he appeared to be nearly sitting up among us.

Standing on the raised platform, it was impossible for me not to see Sonny Joe while I sang, so I turned my body sideways to avoid looking, and sang the refrain.

One verse and one chorus and I backed up on the platform getting ready to leave, and then I felt a poke in my back from Daddy and he motioned for me to keep singing.

The wailing and the grieving had already reached a level that was hard to sing over. My voice wasn’t big like Mother’s. She could send any kind of song to the back of a huge auditorium, and she barely needed a microphone to do it.

The second verse about knocked the wind out of me. I had to lean closer to the microphone to be heard, which turned me back around, facing Sonny Joe.

Somewhere the load is lifted,

Close by an open gate,

Somewhere the clouds are rifted,

Somewhere the angels wait.

We left town soon after that, headed back to Texarkana, where we would be headquartered while we traveled the revival circuit again. When Daddy announced to the church that we were leaving, he said, “The Lord has called us back to the evangelistic field.”

I was out of breath and there wasn’t going to be another chorus, except that Daddy stepped forward and stood next to me and added harmony in his high, lonesome tenor.

Somewhere, somewhere

Beautiful Isle of Somewhere,

Land of the true, where we live anew,

Beautiful Isle of Somewhere.

As soon as we were done, I left the platform while Daddy brought the microphone back up to his height to begin his eulogy. As I stepped down, Sonny Joe’s mother looked at me with her face red and contorted and wet with tears. I stopped in front of her and held out my arms to the little girl in her lap.

She lifted the girl up to me and I walked out with her, straight down the aisle of the church and outside into the summer sun. And that was how I escaped having to file past the coffin at the end of the service. Anybody who could stand up was expected to walk past the casket and pause for a moment. Not to do so was disrespectful.

At the social hall, food was laid out by our Women’s Society. These churchwomen would hand you a plate of food and gently begin a story about your dearly departed that would have you believing they were close, even if nobody knew much about your people at all.

When Daddy stopped by the social hall, people hugged his neck and tried to get him to eat something and they were overly solicitous and I realized, they think their own pastor hit that little boy and killed him and now they believe that through the strength God gave him to carry on, here was this young preacher with such a heavy heart, putting aside his own personal grief about the terrible tragedy long enough to comfort the little family.

Beau didn’t go to the social hall.

We left town soon after that, headed back to Texarkana, where we would be headquartered while we traveled the revival circuit again. When Daddy announced to the church that we were leaving, he said, “The Lord has called us back to the evangelistic field.”

We were packed and ready to go. Our car would pull a trailer filled with the few belongings we would take from that parsonage, mostly our own musical instruments and equipment.

Beau appeared at the screen door, cupping his hands over the sides of his face to see inside, peering toward the kitchen. Though it was early in the morning, breakfast time for us on a regular day, the oilcloth was already off the table. Nothing sizzled in a skillet on the stove. There were no biscuits and gravy, no leftover fresh peaches from last night to drown in cream, not even a hunk of cold cornbread to crumble into a glass of buttermilk.

Daddy let Beau in. “You hungry?” he asked. He looked in the icebox. “I got some milk here.” He shook a box of corn flakes. “Cereal?”

Beau nodded and sat down at the bare table. Daddy rattled the last of the corn flakes into a bowl. The dishes that came with the parsonage would stay there for the next preacher to use. The rest of us drifted away, leaving the two of them in the kitchen.

For years, we followed news of the Hilliard family like everybody else who ever lived in that part of Arkansas. When we received letters from Beau, Daddy read them out loud.

“Beau says Velda’s building out at the farm again.”

“Beau says he’s startin’ up a company with his brother.”

It seemed impossible that anyone could keep a secret as big as the one our family was keeping. Would anyone question why Beau wrote checks for years and years to support Sonny Joe’s mother and sister, or did folks just believe that’s what people like the Arkansas Hilliards do—take care of the less fortunate?

I wondered if it was Daddy’s one big lie that gave Beau his fresh start. Since Beau hadn’t yet begun anything at all when we met him, did the lie provide the first step toward him having some kind of a life? Maybe that seems like a stretch, to say that one lie could turn somebody else’s life around. Still, you couldn’t help but wonder.

Nothing Beau accomplished, none of the success stories in the letters he wrote ever erased, for me, a single detail of that Sunday. Locked in my forever-memory is the image of his face, a reflection from a well of loneliness so immense I doubted anyone could ever plumb its depths. Not even his own Daddy finally declaring himself proud of his son would alter my picture of Beau.

Sonny Joe’s name was never mentioned in our family. Nobody talked about his mother or that little girl. Because of who was driving the car that killed him and because of who told the lie, and because we had so quickly moved away from church people who knew him, we were not around to hear the boy’s brief life story become the kind of memory that could be embellished through retelling in the Southern way.

I never could let Sonny Joe slip away, out of mind. Years later, I got in touch with a woman from that Arkansas congregation. We talked about my family’s departure. She said how sorry she was that Daddy felt like he needed to go.

“Everybody knew it was Beau killed that boy,” she said.

“But Daddy never said.”

“Everybody knew.”

When Old Man Hilliard died, still a Baptist, he bequeathed his home, the biggest house in town, to the Pentecostal church to be used as a parsonage.

About the author

Anita Garner, born in Arkansas, now lives in California, where she writes about the South and family and music. She was raised in front of microphones and never left. She has been a radio deejay, a TV announcer, commercial voiceover talent, and a writer and producer of syndicated shows. Her book, The Glory Road: A Gospel Gypsy Life is published by University of Alabama Press. A stage play based on her book, The Glory Road, debuted in Los Angeles, with a new version coming soon. This story is from an upcoming collection of essays, Musical Houses.

Hi Anita, what an amazing story, and I’m so glad to see you work here in Salvation South. While the world of Pentecostal churches is foreign to me, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” is not. The last time I heard my sweet Advent Christian mama play that song (in ragtime) was in the chapel at the nursing home in which she lived her last days. We played it at her funeral. Best regards, Deb

Hi Deb – “Leaning…” still a favorite, one of the comfort songs I sing to myself while driving. I’m glad you enjoyed the story. Nice to meet you here.