Beyond the Coral Reefer

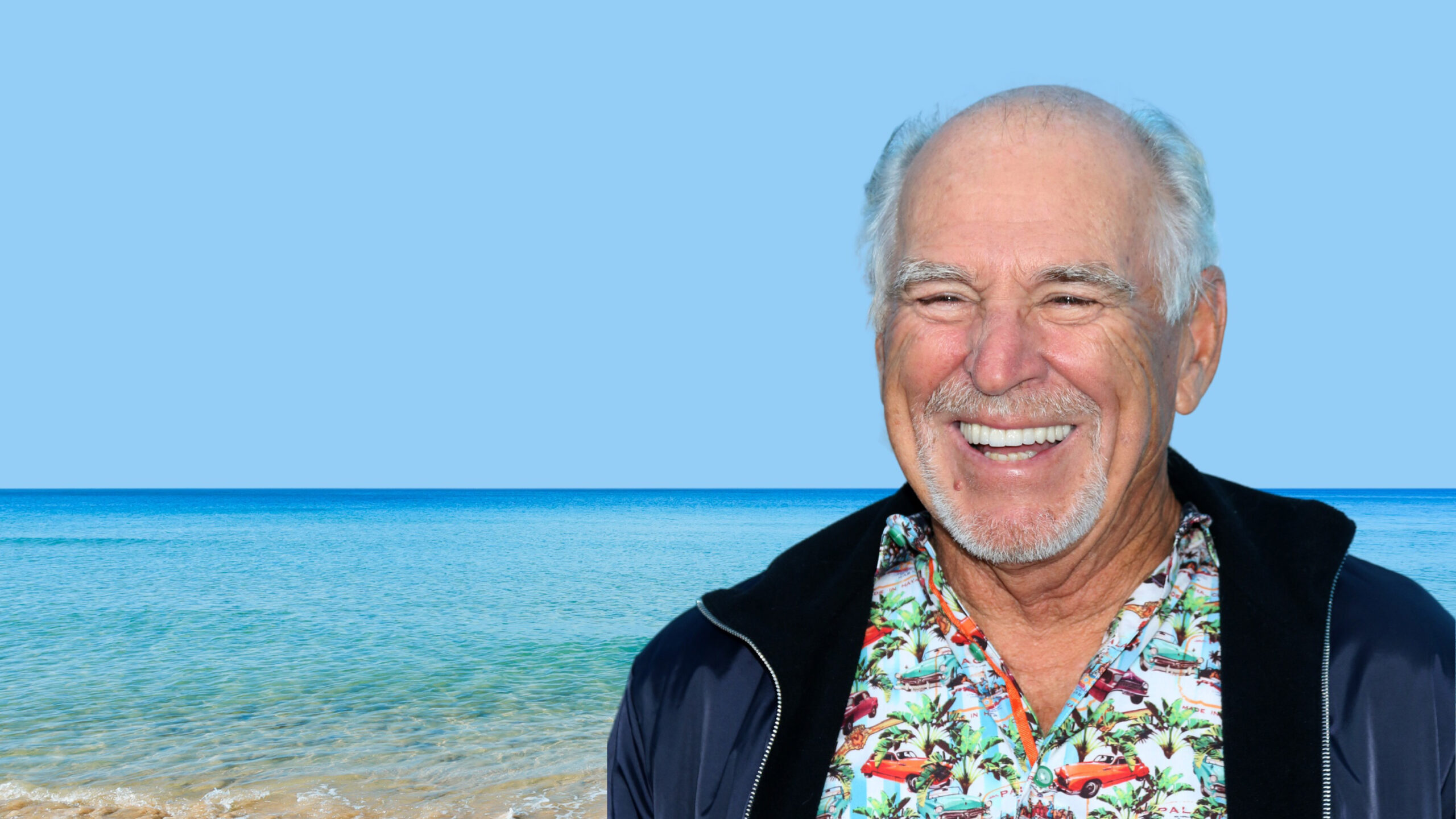

Jimmy Buffett sails away to his own particular harbor.

I liked watching the ne’er-do-well golf pros. They kept everything cool, somehow contraband and just beyond the true reach of a thirteen-year-old girl who was too thin and absolutely curious about what the grown-ups didn’t see because they weren’t paying attention.

Songs about smugglers, washed-out drifters, deadbeats, and writers would drift from their back room, occasionally with a waft of steel guitar and some short blasts of harmonica. The voice felt just like one of those naughty golf pros—warm, familiar, welcoming, wry—except it had some flannel to it, some molasses and a bit of cayenne as it flowed over notes that lifted and fell like the curtains on a slow, humid night.

He sang of a Florida I knew from going to Pompano, Delray, Palm Beach to work on my golf game during the six or seven months when Cleveland wasn’t hospitable to that sort of thing. When his voice drifted out the bag room on a small gust of gasoline, dope smoke, and sweat, my ears pricked up for the stories, always the short stories about pirates looking at forty, men going to Paris to seek something, lives intersecting in Montana...on Monday.

It was all so romantic. Even before I knew about “Margaritaville,” because I lived in a place and time before that Key West loser’s lament became the good-time, freak-flag National Anthem. Somewhere in the delta between personal responsibility and screw it, that song plumbed the awareness of a man who knew better, but just didn’t care.

Jimmy Buffett must have been changing labels. I bought all those ABC/Dunhill Records–it seemed–remaindered at Record Theater at the Golden Gate Mall. A1A , named for the two-lane road that ran along the east coast of Florida; the sunk skiff Living and Dying in ¾ Time that was too hillbilly on first listen, with “West Nashville Grand Ballroom Gown” reminding me of too many of my babysitters; A White Sport Coast and a Pink Crustacean, whose “Grapefruit Juicy Fruit” felt like something I was living, a Gatsby world for a barely teenage Catholic girl, hoping to get a golf scholarship, riding to another tournament. And Pink Crustacean also had the slinky “They Don’t Dance Like Carmen No More” that prompted when my father to wax rhapsodic about Carmen Miranda—and then wince when “Why Don’t We Get Drunk (and Screw)” rolled up.

Back then, everything was either “cool” or “lame.” Cool, of course, came in degrees. Buffett was that uncle your parents wouldn’t let babysit, even if he could talk to them about sailing, literature, or Gulf Coast resorts. That made his sangfroidthat much more delicious to a kid sitting on a work table in a back room of a golf club, not getting all the references.

“Margaritaville” wasn’t a hit when people started singing it, just the self-confession of the guy who drank himself out of the deal—and wasn’t 100 percent sure he cared as the hangover throbbed. He was coping, tequila, ice, lime, and blender. For a washout, it was perfect.

Buffett painted a Florida of blacktop turned gray by the sun, the old people in plastic shoes, Walgreens, and crusty ne'er-do-wells in barrooms watching the ceiling fans turn.

All the sun slaves loved it. Work hard, party hard, recover, then you’re onto the next.

Buffett painted a Florida of blacktop turned gray by the sun, the old people in plastic shoes, Walgreens, and crusty ne'er-do-wells in barrooms watching the ceiling fans turn. He got the Key West of Hemingway, whom I already adored, Tennessee Williams, who would beguile me in college, as well as the next wave of macho literary and creative bros Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Guy de le Valdene.

Key West was for pirates. Dusty, dirty, chickens roaming the streets, space between buildings that held Lord knows. It felt like electric creativity when my father and I would escape from “practice,” head South over the Seven Mile Bridge and set to walking the streets like the tourists we were: an older Dad and a scrawny little tomboy, both sponges for whatever was in the air.

He’d lie to Mom about where we were. That’s how I knew it was good. And when Buffett’s songs came pouring out of a muscle car’s rolled-down window or in that badly ventilated back room, I was right there at Sloppy Joe’s on a barstool next to my father.

“This is the stuff, pro,” he’d tell me. “This is...the stuff.”

Buffett was snide about the right stuff, tender with the good stuff, and savoring of the naughty stuff. Even before he turned into a billionaire industrial conglomerate of frozen drink machines and retirement communities, he understood not just what mattered, but how.

If the Eagles were “The Dirty Dozen,” Buffett was Butch Cassidy’s “Sundance Kid.” He had the escape route planned; he wasn’t backing down, and he wasn’t afraid to hit the tricky spot. When Southern California rock included Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Warren Zevon, J.D. Souther, America, Neil Young to some, Poco to others, Buffett was the Southern cousin, leaning a bit more to the folkie side of singer/songwriter.

He ran with Jerry Jeff Walker, Jesse Winchester, Steve Goodman. He got those traditions. He exhumed Lord Tom Buckley’s “God’s Own Drunk (and a Holy Man),” which he delivered with a hilarious ramble on his 1978 live album, You Had To Be There. It was that notion of street musicians playing for tips and vibes—a secret handshake and a wink to a counterculture that was as romantic as it was pungent.

Postcards from a life I didn’t have agency over. Yet. People I didn’t know. Yet.

But I leaned into the poetry, loving the notion of captains and kids, characters painted with the same detail John Prine conjured. But where Prine could be profoundly sad or lonely or conscience-tugging, Buffett was more the brio of the literati he was running with.

Dreaming dreams inside the songs has a strange centrifugal force. Like so many people who drift into the world not quite sure where they’re headed, it can pull to you things you never intended. Alex Bevan, my first folk-singing idol who befriended a wet-behind-the-ears kid, knew Buffett from their days playing National Association of Campus Activities showcases, trying to get regional college dates. He’d talk of their intersections on the road: afternoons in laundromats, talking about Goodman, Jerry Jeff, and whatever.

“People ask me, where in the hell is Margaritaville?” Buffett tells the crowd on You Had To Be There, after referencing the possibility it’s a little island in your mind or the bottom of a tequila bottle. Then he proclaims, “It’s anywhere you want it to be, baby...”

Buffett hadn’t blown up yet. Bevan made him seem real-sized. Even sneaking into FM, a film about free-form, big-business rock radio, with cameos from Buffett and Ronstadt, the notion of pirating someone’s concert for broadcast seemed delightfully on point. In Urban Cowboy, he took that out-West cowboy nonsense and lacquered dancefloor country with his zesty “Livingston Saturday Night,” no doubt informed by his writer friends who fled Key West for Montana.

And then I fell out of the sky into St. Andrews School in Boca Raton, pursuing that college golf scholarship. It was a co-ed school with very rich kids who were sophisticated in far more fast-track ways than Ohio. That was where I met Valerie.

Valerie de la Valdene, heart-shaped face, tilted smile, and a wash of ebony hair falling across her eye, was the daughter of a count. She was also Buffett’s godchild, and like me, a young’un used to running with older kids; she couldn’t drive, but she was one of us. If Eloise had been raised by adventurers, she’d have been Valerie, who ran up and down Worth Avenue barefoot, laughing madly and plotting the next adventure.

It was Valerie, who got us the tickets to Buffett’s annual Christmas show at Sunrise Musical Theater in Ft. Lauderdale, who said, “You should review this for the Bagpiper,” our school paper. Being such a big Florida icon—even then—it seemed to be the most perfect idea. Until they used that issue of the paper for the annual fundraising drive, missing my smirking reference to “Why Don’t We Get Drunk (and Screw)?”

What would Jimmy Buffett do? The question became my sextant and compass. Looking at St. Andrews’ Dean Jack Bower, who was braced for antics, I exhaled slowly, smiled innocently, and said, “Obviously these people are not music lovers...”

Jack Bower could barely contain the laughter. His face turned red; the howl was trapped in his throat. A theatrical man, husky but not fat, his eyes danced as he looked at me, suggesting I keep talking without saying a word.

“Dean Bower, that is the name of the song, and it was a climax to the show. It was bawdy and brazen, but also self-deprecating and self-impaling. To not say it happened would be to not tell the story properly.”

He couldn’t take my mealymouthed sweetness. I was not that kid. He knew it. Barking as a laugh escaped, he managed, “Get out of my office. And please, Holly, be smarter. please. The donors are important. They’re paying the bills.”

Turning in the doorway, I tried a Hail Mary pass.

“Would it help if you knew I went with Valerie?”

I smiled. He laughed harder. It was implicit: while Buffett was the dope smugglers’ personal hero, he was also a saint in South Florida. Though his manatee awareness campaign was a few years off, he quietly did much for the region that was overrun profiteers wanted to pave the Everglades.

“Get out, stay out of trouble. You know what to do.”

Yes, whatever Jimmy Buffett might do.

Still, he was quicksilver. Buffett sightings everywhere. Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert on TV, concerts at Blossom Music Center, Rolling Stone, softball games against publications and radio stations. It was a different time and place.

One day during college, while clerking at the Miami Herald, a call came through to the general features desk.

“HELLohhhhh,” the voice came down the line, “How are you today?”

No one was ever friendly on that extension. The euphoria felt real, the voice familiar.

“Honey, would it help if I introduced myself? This is Jimmy Buffett, and if the restaurant sucks, I promise we won’t get you fired.”

“I was wondering if you could help me...I am trying to figure out where to get some good Thai food down here in Dade County. Can you help me?”

“Well, sir, um, we really don’t provi...” I was trying to avoid making a Herald endorsement.

“Honey, would it help if I introduced myself? This is Jimmy Buffett, and if the restaurant sucks, I promise we won’t get you fired.”

I turned purple. Of course, he won’t. He gets the plight of the late teenager/early twenty-something. I gulped; didn’t want him to think I was stupid.

Putting him on hold, I asked a couple of the folks on the desk whom I trusted. Got back on the phone. Trying to “sound” like a pro, I picked up, “Okay, not sure where you are in the county, but the place you want is called Tiger Tiger...It’s down Dixie, south of the Gables, and it’s delicious. I think you’ll like it.”

“Awesome, baby. And if you can get out of there, you’re welcome to join us.”

He laughed and was gone. Dixie Highway was an easy navigation, especially in the ’80s. Just get to Coral Gables and start looking; that restaurant was dark wood. It’d be easy to spot.

Whether it was a pleasantry or a genuine invitation, I was too intimidated to show up. Besides, real life drive-bys are only magic when you’re not stalking.

A year later, I would get to interview Dan Fogelberg, who was playing the NAMM Convention in Hollywood, Florida. He had a bluegrass album, High Country Snows, coming, and I stalked my story with a vengeance. It’s hard to say no to a kid with shiny straight hair in a striped T-shirt with hope in her eyes; the tour manager agreed, saying I needed to chase their limo to Ft. Lauderdale so I could meet him in the restaurant and talk while he had his dinner. Nina Avrimades, his manager, was there; I tried to not be too excited, but I knew her name from Buffett’s record covers.

The Fogelberg interview went impossibly well. Turned out he’d had his dinner sent to his room; he was only going to have soup with me. But he ended up staying for the entire hour. When he left to go change, I set upon the lovely blond-haired woman, asking questions about what she did, how she did it.

“You know, he normally hates these things,” she confided. “Dan genuinely enjoyed that.”

Screwing up my courage, I ventured the big ask. I opened with the obvious, “You know Jimmy’s the Grand Kahuna down here. No one is bigger.”

She laughed. She saw the setup, and she knew he wasn’t “in record cycle” or “touring.” We left it that she’d think about it, see what she could do. A couple months later, Buffett called my dorm room—and the Herald ran the piece.

So did Country Song Round Up, the world’s oldest country fanzine. My canny editor there told me about Buffett’s connections to Nashville, the reporting for Billboard magazine, the days hanging out at the Exit/In, Closed Quarters, and other creative haunts. Suddenly, the Jerry Jeff Walker stuff, the steel guitars, and the actual country undertow made sense.

He existed in our world like twinkle lights in a bar; look up and smile at the glimmer in whatever other clutter was around. He knew poetry, knew how to deliver it—and he knew how to revel like an Endymion Mardi Gras float, tossing ravers out to the fans like so many fistfuls of beads.

It opened my mind to how impossible things can merge and converge; made Willie Nelson not the only one who could tap authenticity in seemingly opposing realms of music. But where Nelson was truly making country safe for the alternos, Buffett was slyly interjecting country music into songs people loved and never letting them realize it was “liver.”

It always seemed to be that way with this Buffett character. He existed in our world like twinkle lights in a bar; look up and smile at the glimmer in whatever other clutter was around. He knew poetry, knew how to deliver it—and he knew how to revel like an Endymion Mardi Gras float, tossing ravers out to the fans like so many fistfuls of beads.

It wasn’t that Buffett came full circle, so much as music had turned all the way around to where the kid born in Pascagoula, Mississippi, and raised in Alabama started his journey. Sure, there’d been Lear jets, misadventures, crazy stories, mysterious substances, inside jokes, sports teams and 60 Minutes, but there was more to come. Writing his own novels about Joe Merchant (plus memoirs), launching a chain of cheeseburger restaurants that turned into hotels, Broadway shows, football stadiums, creating a space for the regular folks to get a little tropicrazy and have the license to let their freak flag fly high.

All that was ahead of him. Records were a place to give his creativity a home. He was still everybody’s favorite “oh, yeah” songwriter/singer/supernova, but the Parrothead ubiquity was just quickening. “One Particular Harbor” from that era was beautiful, a lulling melody that spoke of refuge and peace/piece of mind. It wasn’t what country radio was doing, but the video—possibly shot in Polynesia—was close to four minutes of mental escape every time it rolled up on CMT or TNN.

That escape was everything. As MTV blared and pulsated, Buffett was saner, smarter rebellion against the nine-to-five status quo. His touring business grew more robust without radio; his legendary Coral Reefers became more formidable—at different times, Timothy B. Schmit (the ether-high vocalist with the Eagles), Josh Leo, Tim Krekel, Will Kimbrough, especially the tenderest-hearted songwriter/guitarist Mac McAnally, all artists in their own right.

Suddenly, it wasn’t about chasing hits, but the longevity of classic tracks, the opportunity to convene with your Parrotheaded brethren, to sing these songs together. Buffett was the grandmaster—and he took his duties seriously.

He used that power to launch Margaritaville Records, where he signed original Nashville compatriot Marshall Chapman for her It’s About Time: Live from the Tennessee State Women’s Prison project—and a neophyte trickster/writer acolyte of Jerry Jeff and Keith Sykes named Todd Snider, whose mostly talking blues “Alright Guy” caused a sensation.

Snider, a free spirit, and Chapman, a lanky rock guitarist with blazing charisma and a drawl for days, embodied the notion that outside the lines is the only place to color. Original voices and perspectives, they brought it with a burning intensity, each as different as the other—and both in contrast to Buffett’s cool.

Chapman, opening for Buffett at the Hollywood Bowl, knew how to bring a Chrissie Hynde panache to a bare-bones, rock-and-soul attack. She and her Love Slaves left those fans panting for more, and when the main dish is Buffett, that’s saying something.

Springsteen wrote, “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” but Buffett lived it. Top-to-bottom, front-to-back, inside-out, and upside-down.

Not only was Buffett a great judge of their talent, but he was also willing to share the stage with them with Chapman and Snyder—a woman who in the ’70s was known as “the female Mick Jagger” and the sly songwriter who loved to do something just to see what would happen, including wandering off from the venue on one tour and not looking back. To Buffett, it was all part of the carnival, the glorious feast Auntie Mame promised in the original Broadway show. If it got twisted, that was part of it.

So Buffett became an icon, larger than life—and somehow still inviting. A Saturday morning superhero, he was the kind of cartoon who was so frisky his skin almost seemed not enough to hold him. The tales of shots fired at his plane over Jamaica; the tales of adventures that inspired William McKeen’s Mile Marker 0; the charities he anchored and advocated for in New Orleans, the Hamptons, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

But even then, it was the random Buffett, the sightings of the man in the wild. Running into him in a purple label Ralph Lauren tux, where he got up and sang some for the wedding of a friend’s son in Palm Beach; laughing jocularly at a CMA Awards after-party after singing “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere” with Alan Jackson; on his bicycle on County Road in Palm Beach, dropping by to see friends at PB Boys Club; or reports that he was out surfing with friends.

Of course, he was. For while his brand was the guy who lived his life on his terms—St. Bart’s, St. Kitts, Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, Jimmy Buffett actually inhabited a devil-may-care world where he just was. Not rejecting the fanfare, but laughing it off as he went.

Which isn’t to say he ever stopped thinking about what his next creative step might be. A million years ago, reading the Sunday New York Times and Saturday Wall Street Journal at the pool at a fancy Vegas hotel, he spent a little time with an emerging country artist, sharing some wisdom, talking about football and demonstrating how little one needed to change. That lesson served Kenny Chesney well; he remains indifferent to fame, investing his heart in the buzzy byproducts of making people happy with glorious concerts that remind them the joy of being alive.

When he played the annual Everglades Benefit in Palm Beach County, usually with some splashy single name guest, the high dollar tickets flew out. When the Gulf Coast was destroyed by weather, he got a few of his famous friends—and came in to raise millions of dollars. Big shows with an undertow of fun within the wreckage, offering hope as it solved or helped with problems that were critical.

Springsteen wrote, “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” but Buffett lived it. Top-to-bottom, front-to-back, inside-out, and upside-down. It was a tilt-a-whirl, centrifugal force of ebullience—and it never flagged. Whether Las Vegas, peekingout from the wings, or West Palm Beach’s “what name is it this year?” amphitheater in the swelter, Buffett always delivered exuberance and delight. If you came with a squad or a date, we are all one once the singers slithered onstage, the tin drums started their rolls, and the churn started turning.

In 2018, fresh from induction into the SOURCE Hall of Fame, which recognizes women in the music industry behind the scenes, I boarded a plane to fly across the sea. All alone, my destination was Paris. To mark the triumph of the unseen, it didn’t matter that no one else could join me.

Raised on the poetry within songs, hearing Jimmy Buffett sing “He Went to Paris” at La Cigale seemed the most perfect way to remember that young girl who didn’t quite understand all the grownup emotions, but recognized the power in those songs. Deceptively engaging, Buffett—like the Texas songwriters, the wild authors and filmmakers of Key West—knew that if there wasn’t conflict or a yearning, the song didn’t lance whatever was stuck in the listener’s heart.

It wasn’t that I was numb from the music business, but it extracts a toll on women who don’t fly by their looks or native charms. I needed to remember those moments when a song sounded like something I could—and must—touch, and my heart sped up at the way the images often stacked up to create some truth about living.

Paris, as Audrey Hepburn declared, is always a good idea. The streets alive with passion for life, the different size glasses of wine you can order, the fabulous cafes, the bookstores, walking along the Seine, over the ancient bridges, the Deux Magots and Café des Flores, as well as the D’Orsay, the Picasso Museum, and yes, the teeny Hemingway Bar at the Ritz.

Jimmy Buffett believed in his songs, his friends, the characters who’d inspired him. As long as he had those people, a little imagination, he’d find a way. Oh, and that way made him a billionaire; he had the last laugh on the music-business know-it-alls.

Stopping at Saint-Roch, one of Paris’s oldest Catholic churches, I knelt in a chilly stone cathedral and wept for all that life had given me. So many blessings, adventures, wonders, people, and dreams that came true; not just my own dreams, but the dreams I’d midwifed for artists who didn’t always see what I dreamt for them...artists who didn’t always see how their music changed lives.

Sitting so close to the stage later that night, taking notes to always remember, I was overwhelmed by how much joy could be delivered—also, the heroism washed-out characters could have being true to their own shattered lives. “He Went to Paris” was, indeed, the miracle I believed it would be.

He went to Paris, looking for answers, to questions that bothered him so.

La Cigale, there in the 18th Arronddisement, had quite the history. Built in 1894, Maurice Chevalier had played there; later Jean Cocteau would stage avant-garde evenings. It would become a movie theater in 1940, ultimately falling into a screening house for kung fu movies, then X=rated films, but always it remained. Deemed a historic building in the 1980s, the French recognized its intrinsic essence—and Philippe Starck was drafted to return it to its former glory.

The metaphor was not lost on me, or the fact this less-than-1,000-seat venue was where Buffett chose to play. Like Key West in the ’70s, it was the fabulous dissolute chic that delivers dignity and delight right where you are.

I had traveled alone, but I sat in that row at La Cigale with every me I’d ever been. The little girl run off with the naughty golf pros, the baby rock critic people didn’t take seriously until they saw my words, the young dreamer working in a world where a journalist’s stories weren’t vanity, but a truth for the tribes, a voice that shaped how people saw the worlds and the artists who mattered, a business reporter, a major label department head who hated the way decisions were never for the artists, a boutique artist development and media relations innovator who’d fight for her clients, a battered survivor of a callous industry, a truth-teller when it mattered—and nobody wanted to listen.

It got crowded in that row. But it also got epic, because Jimmy Buffett had also flown into headwinds over and over again. He never won a Grammy; only had quantifiable hits on country radio with people like Alan Jackson. He didn’t care.

Jimmy Buffett believed in his songs, his friends, the characters who’d inspired him. As long as he had those people, a little imagination, he’d find a way. Oh, and that way made him a billionaire; he had the last laugh on the music-business know-it-alls.

Not that that was his motivation. Standing onstage, with the smile slicing his face like wide open like a ripe mango, eyes sparkling at the naughtiness of Parrotheads converging on Paris in some kind of electric mojito acid test, there was revelry to be had—and songs, poetic and ribald, to be sung.

That way the joy and the mission: honor what is however it was, remember the beauty, hang onto the high jinks and never, ever doubt the songs.

For someone who tilts at windmills, gets treated more poorly than people would ever imagine, whose best friend once squealed—driving around the streets of L.A. as two unhinged medium-20-somethings—“You could be HER, Holly Gee!” as Dylan’s “Sweetheart Like You” poured from her tape deck, La Cigale took back that fate which stretches you across a rack until you break and gave me back the effervescent joy of serving the music. That was what it’s about..

Even when the king of the parrot pirates was out flying his planes or chasing the sun, talking about good times or creating more memories, he was always braising those songs. Living like he sang, laughing like he wrote, it was all the same beautiful ecosystem so many people drew their moments of release, of elation, of crazy wild “oh yeah” from.

It was money I probably shouldn’t have spent, but it was the best value I’d seen in a long time. On the plane back, I smiled and exhaled and mindfully let all the good that is my life flow through me. “This is what being present feels like,” I marveled.

Jimmy Buffett, more than anything else, was absolutely, truly, completely present. Like his friends from Key West, adventurers all, he understood: Immersion is everything. Dive deep. Go big. Go crazy. Have fun. Feel it all, revel in it—and let what makes you feel alive be your navigational buoy.

It was a lesson that mattered profoundly.

When the call came at 5:11 a.m. from Kenny Chesney who’d texted me the night before, he didn’t have to speak. Just “he’s gone,” and gravity fell out of the room. It was dark, too early for morning to even think about breaking, and yet...

When we hung up the phone, I pulled the new rescue spaniel to me. Petted his silky head and felt tears fall off my face onto his ears. “Oh, Corliss,” I told the little guy, “you have no idea. To find someone who lived as most artists who pretend to, who embodies all the happiness that comes from being present, who wrote about places that mattered and being ripped down and forgotten...”

So many songs, so many moments, so much life.

And not just Buffett’s, but our own. I found “He Went To Paris” rising in my throat. Not because I called it up, but something in my muscle memory sent it through the transom. Singing softly to a red cocker spaniel who was licking the tears from my face, I couldn’t believe when I got to the end...

There it was: the words the old man, who’d seen World Wars, the Spanish Civil War, great love and horrible loss, had told Buffett more than half a century ago. Suddenly, there was the elegy for us all.

“Jimmy, some of it’s magic, some of it’s tragic

“But I had a good life all the way.”

About the author

Holly Gleason is a Nashville-based writer. Recipient of the Los Angeles Press Club's Southern California 2023 Entertainment Journalist of the Year, Music Criticism and Best Entertainment Feature, News (Magazine) Awards, she was the editor and a contributor to Woman Walk the Line: How the Women of Country Music Changed Our Lives, which won the Belmont Books Award for best country/roots music book, and co-authored Miranda Lambert's New York Times best-seller Y'all Eat Yet? She's written for Rolling Stone, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, Oxford American, No Depression, Paste, Texas Music, Spin, Musician, CREEM, Interview, Playboy, thePalm Beach Daily News, the Vineyard Gazette, Harpers Bazaar, Rock & Soul, and Mix.

Great story. It’s nice to read long-form journalism.

“Buffett—like the Texas songwriters, the wild authors and filmmakers of Key West—knew that if there wasn’t conflict or a yearning, the song didn’t lance whatever was stuck in the listener’s heart.”

High cotton here.

Dammit. Write my obit in 50 years