The Hero Who Wanted to Die

Daniel Wallace's brother-in-law was his hero. But in the journals he left behind, Wallace discovered the darkness that claimed his idol's life.

Daniel Wallace thinks of himself as an average guy. I do not. Never have. He writes like no other Southern writer I’ve ever read.

Twenty-five years ago, when he was thirty-nine years old, Wallace’s first novel, Big Fish: A Novel of Mythic Proportions, came into the world. I read it and knew instantly he was a writer unlike others. In the preface, Big Fish’s narrator, William Bloom, walks with his dying father, Edward, to the banks of a river. The old man takes off his shoes and socks and dangles his feet in the clear water. He takes a deep breath and says, “This reminds me.” Young William waits for yet another story. His father had always told him whoppers, so many Will had grown sick of them. But on this day, he sees Edward Bloom in a different light.

“I looked at this old man, my old man with his old white feet in this clear-running stream, these moments among the very last in his life, and I thought of him suddenly, and simply, as a boy, a child, a youth, with his whole life ahead of him, much as mine was ahead of me. I’d never done that before. And these images — the now and then of my father — converged, and at that moment he turned into a weird creature, wild, concurrently young and old, dying and newborn.

“My father became a myth.”

Wallace then spun that story into exactly what his subtitle promised: a novel of mythic proportions, a tale so tall that even in the South, where we live and die by our stories, it felt like a skyscraper.

Five years later, the award-winning British director Tim Burton turned Big Fish into a critically acclaimed film starring Albert Finney and Ewan McGregor as the old and young, respectively, versions of Edward Bloom, and Billy Crudup as the young Will Bloom.

And suddenly, people all over the world knew who Daniel Wallace, born in Birmingham, was.

Over the course of his six novels, Wallace consistently shows a remarkable gift for telling stories that smash the walls of plausibility. They are full of people and incidents that simply could not be real, yet somehow wind up containing more truth than even a nonfiction book could.

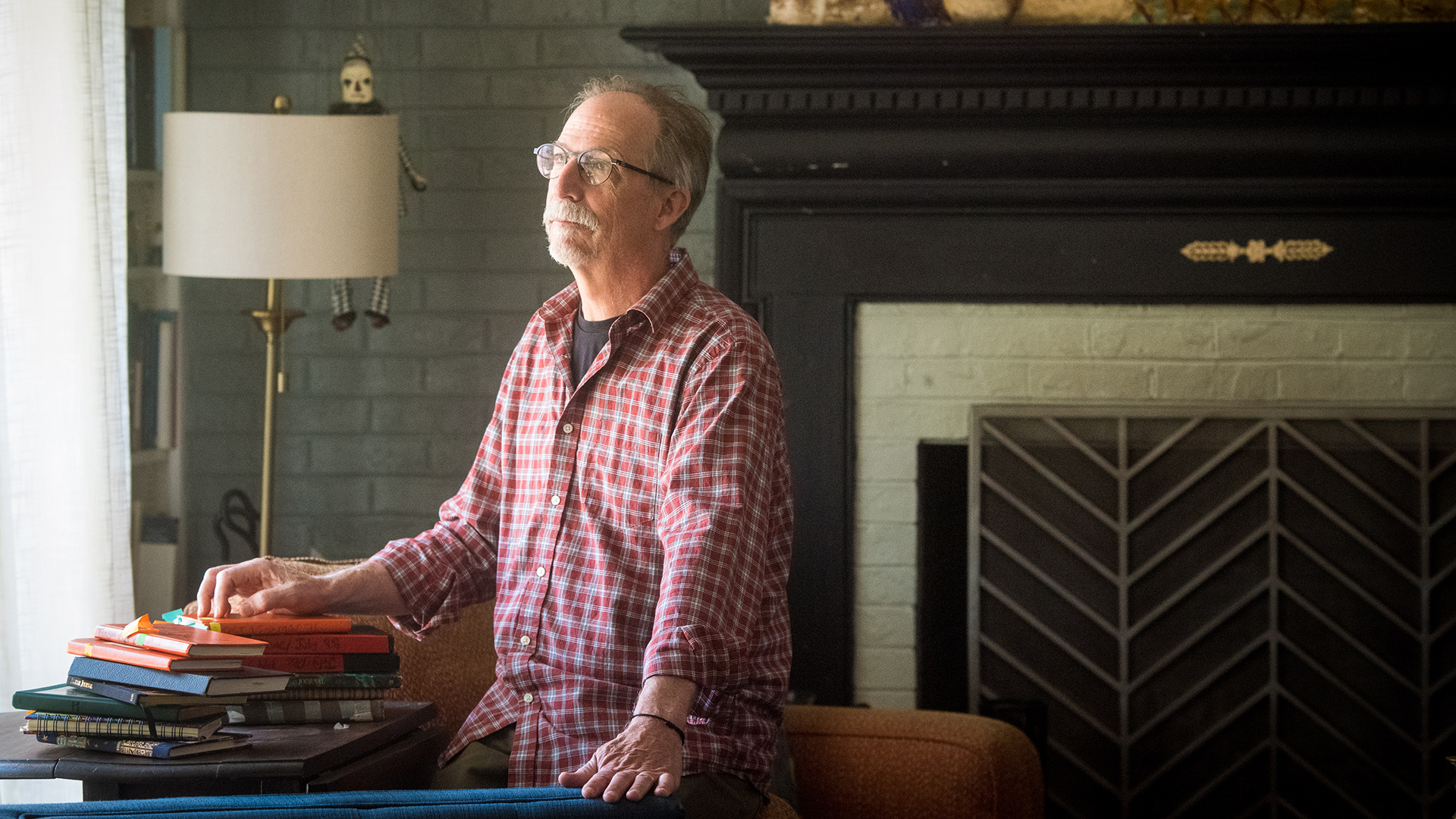

Which is why I was shocked to learn during a phone call two years ago that Daniel was working on his first nonfiction book. From his home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, his alma mater, Daniel told me about his brother-in-law, William Nealy. Daniel was twelve years old when he met William, and their meeting was most dramatic.

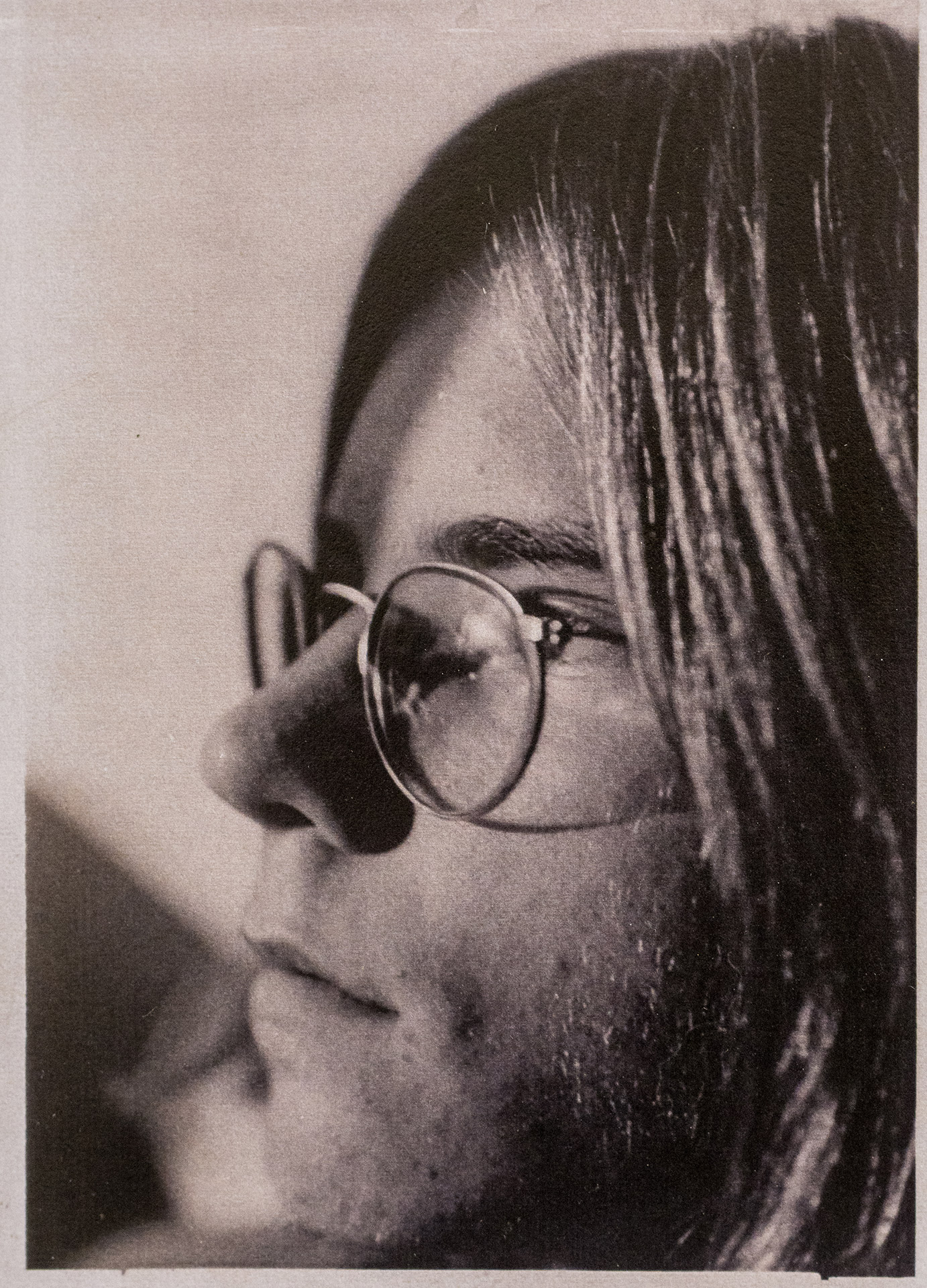

Imagine this: You’re a boy of twelve, and you see a strapping, handsome teenager climb onto the roof of your house and jump off it into your family’s swimming pool. Now imagine that superhuman guy becomes the man from whom you learn almost everything you care about for the next 30 years. Cool as hell, right?

Imagine this: You’re a boy of twelve, and you see a strapping, handsome teenager climb onto the roof of your house and jump off it into your family’s swimming pool. Now imagine that superhuman guy becoming the man you learn almost everything you care about from for the next 30 years. Cool as hell, right?

William Nealy was Daniel Wallace’s hero, role model and friend until he died at age 48.

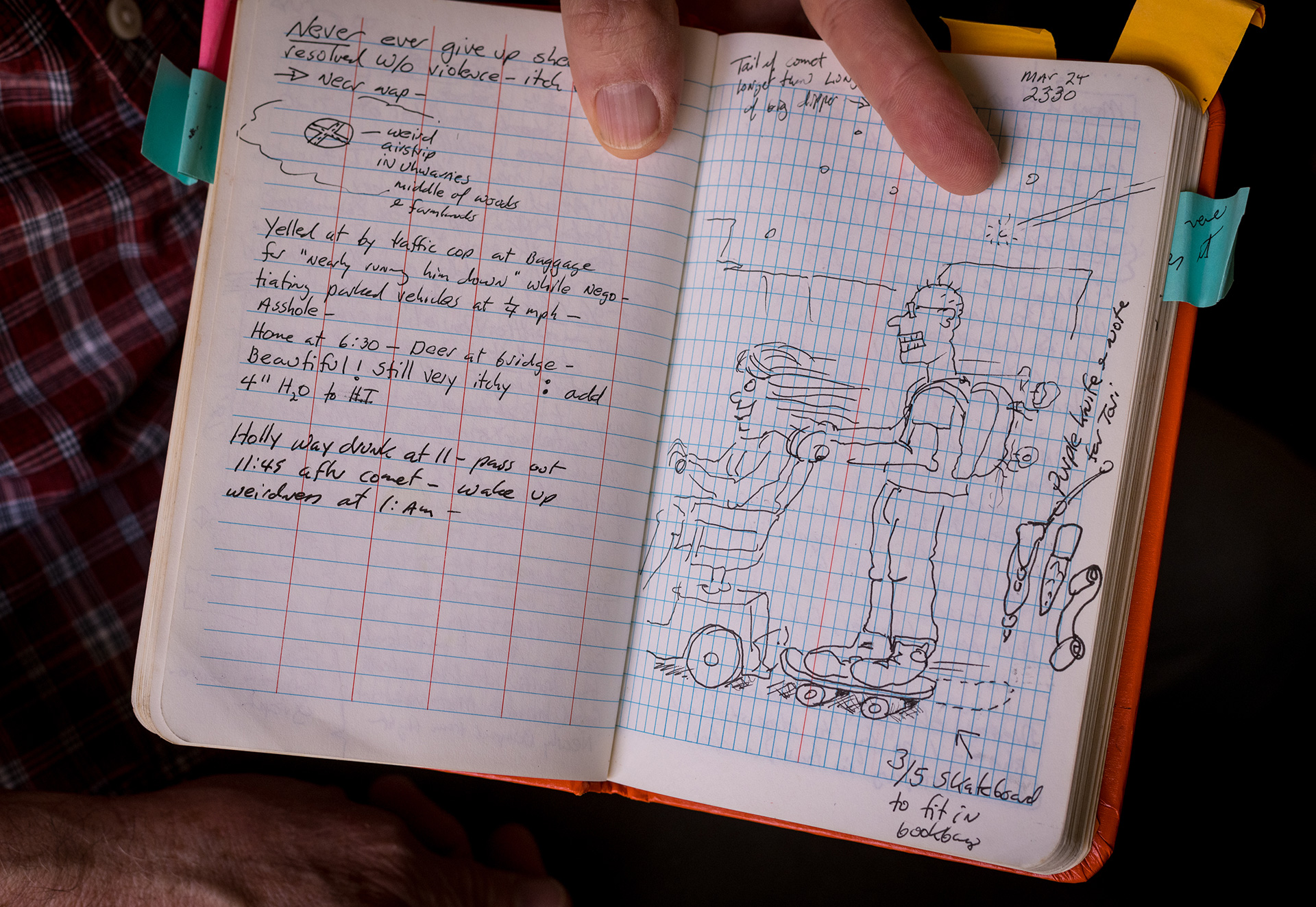

Ten years after William’s death, his wife, Daniel’s sister Holly, passed after an almost four-decade battle with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. As Daniel and the rest of the family cleaned out Holly’s house, they found several boxes full of William’s journals. Daniel told me on the phone that day those journals had shattered almost all his memories of William, his brother-in-law, his mentor, his hero.

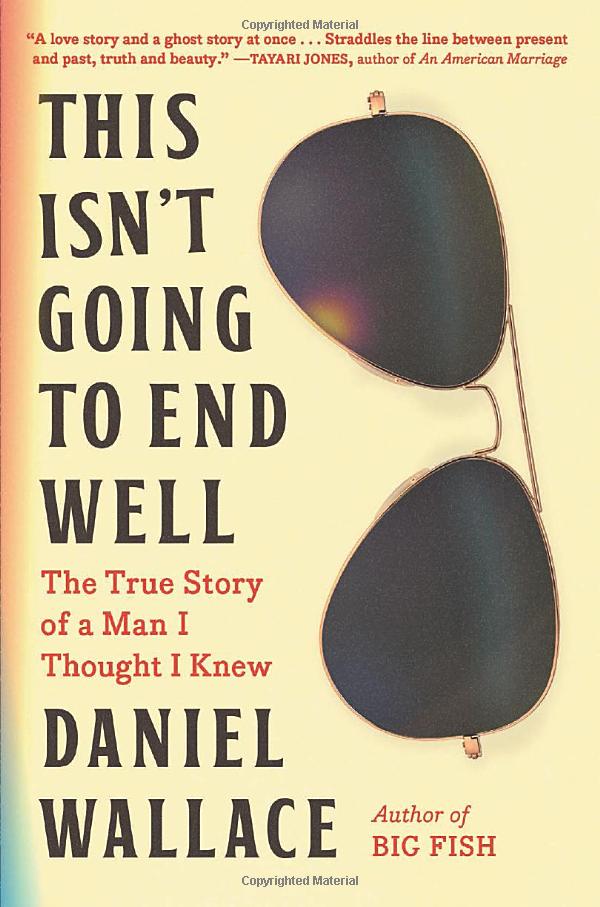

Come Tuesday, Daniel’s first and (so far) only book of nonfiction will become available to the world. It is called This Isn’t Going to End Well: The True Story of a Man I Thought I Knew.

In the eyes of Daniel and most everyone else who knew him, William Nealy had been a man of mythic proportions. He was a whitewater paddler who mapped and wrote about rivers across the South. One can reasonably assume William was at least the partial inspiration for some characters of mythic proportions that Daniel has brought to life in his fiction. How odd then that when Daniel finally writes about the real man who inspired him to write in mythic proportions, the book must be about the shattering of all the myths William created about himself.

This Isn’t Going to End Well is deeply moving, as any reader of Wallace’s fiction would expect. He has never been shy about getting to the emotional heart of the matters at hand. And few characters in modern literature are like William Nealy, seen by the world as an indomitable spirit but wracked every day by dark depression, which he scrupulously hid but would finally drive him to suicide. But the book is ultimately about how we come to terms with the flaws we find in the people we love best. Which is the toughest work of reconciliation that any of us ever do.

Daniel and I sat down for a chat last month to talk about This Isn’t Going to End Well. This week, we’re also publishing an essay by Daniel, written exclusively for Salvation South, called “The Coolest Guy in the World,” where he takes us into the work of deciphering William’s journals. Finally, with Daniel’s permission, we have published Chapter 1 of This Isn’t Going to End Well: “The Boy Who Could Not Fly.”

The interview that follows has been edited for length and clarity.

Chuck Reece: Talk to me about that day in 1971 when you first met William, when he jumped off the roof and into your swimming pool.

Daniel Wallace: It was a perfect prelude to everything that would happen later. I'd just come home from Birmingham University School, which was a former military academy. You had to wear a tie every day. It was all boys at the time. And as I say in the book, I was the most average of the average. I was perfectly average. So yeah, a few years later, if you don't mind me drifting …

CR: Drift wherever you’d like.

DW: Years later, I went to a basketball camp at Vanderbilt for two weeks, and they divided the campers into groups: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. When I was in the intermediate group and at the end of the camp, the coach wrote a little overview of the campers. And I actually just found his note, and he wrote, "Danny is the best player of all the players in the intermediate group." And ever since then, that's sort of how I've felt about myself: I was a mid-range guy in the intermediate group, but at the very top of it. And I feel that way about my writing, too. So there was this implied path for me that changed dramatically without me knowing it that day. I could experience this alternate potential reality. I didn't know that in seventh grade, but that was the prelude for things to come and really the essence of who William was to me and in my life ongoing.

CR: I thought your description in the book of what came over you that day was really powerful. Let me read specifically what I'm talking about: "It was just a wildness, the derring-do. His willingness to take flight — literally — into the unknown, an openness to experience and chance that so far in my short life had not been previously modeled to me by anyone. Whatever I was, he wasn't that, and I wasn't sure how much I wanted to be the me I was. That's what I would learn from him, though, over the years, how to become the me I wanted. Not by being him, but by watching him." Is it fair to say that on that day, William became your hero and one of the primary role models of your life?

DW: Absolutely. And he almost never disappointed me. He always seemed to provide, in a kind of ideal narrative, those things I wanted to believe existed or needed to see existing. His completely tough but sensitive and cool demeanor. His connection with the moment, but also his distance from it, which is, I think, where a writer usually is. The ability not to talk, the ability not to engage while engaging with yourself in the moment. That was what I felt like he was doing.

CR: The subtitle of This Isn't Going to End Well is The True Story of a Man I Thought I Knew. Did William remain your role model all the way until he ended his life, or were you already falling away from that view of him by that time?

DW: One thing I get to in the book is what the nature of influence is in our lives and how hard it is to understand who we are — or to understand the things that have made us who we are. By the time I was approaching 40, I had become who I was. And William, over the course of those years, gradually removed himself from being an active part in my life, although he definitely responded when he needed to or when he was asked to. That being said, by that point, I didn't look to him for much direction. I knew who I was or what I was capable of, and I was out of the oven. So I didn't look to him for mentorship.

CR: One phrase that caught me was a line in your note to readers at the beginning of the book. You write that William "had the worldview of an adventurous teenager all his life." And you didn't see any cracks in that worldview for a long time?

DW: Yeah, I think that's accurate to say. But it’s complicated, because he was in a lifelong relationship with my sister, and part of how I saw him was as a caretaker, her other half. And I don't even mean that metaphorically. He provided half of her life. So that's how I saw him as he got older — emotionally diminished and also physically diminished. His physicality and his ability to be an adrenaline-sports aficionado really was what was one of his saving graces that allowed him not to kill himself for such a long time. Removing yourself from yourself is what sports can do for you. You're really, truly living outside of yourself in the moment. That can sustain you. But as he got older and was forced to live in the tangled darkness of who he was, he couldn't get out of it.

CR: That reminds me of a particular passage from one of William’s journals — a long litany of ailments, both physical and mental, that he's struggling with. And at the end of that list, he says all of them were self-inflicted. He had maintained that “worldview of an adventurous teenager” until he reached a point in his life where he saw those things begin to fall away. And I can't imagine how tragic that must have felt to him. I also found it interesting that, like you say, this was happening in about the time that you were turning forty — and you note in the book that you were publishing your first novel, Big Fish, about that same time. You were thirty-nine when you first sold that book. And so William would've been in his mid-forties by then, which was what? Maybe three years before he killed himself? So many of the journal entries that you reference talk about the frequency of his suicidal ideation.

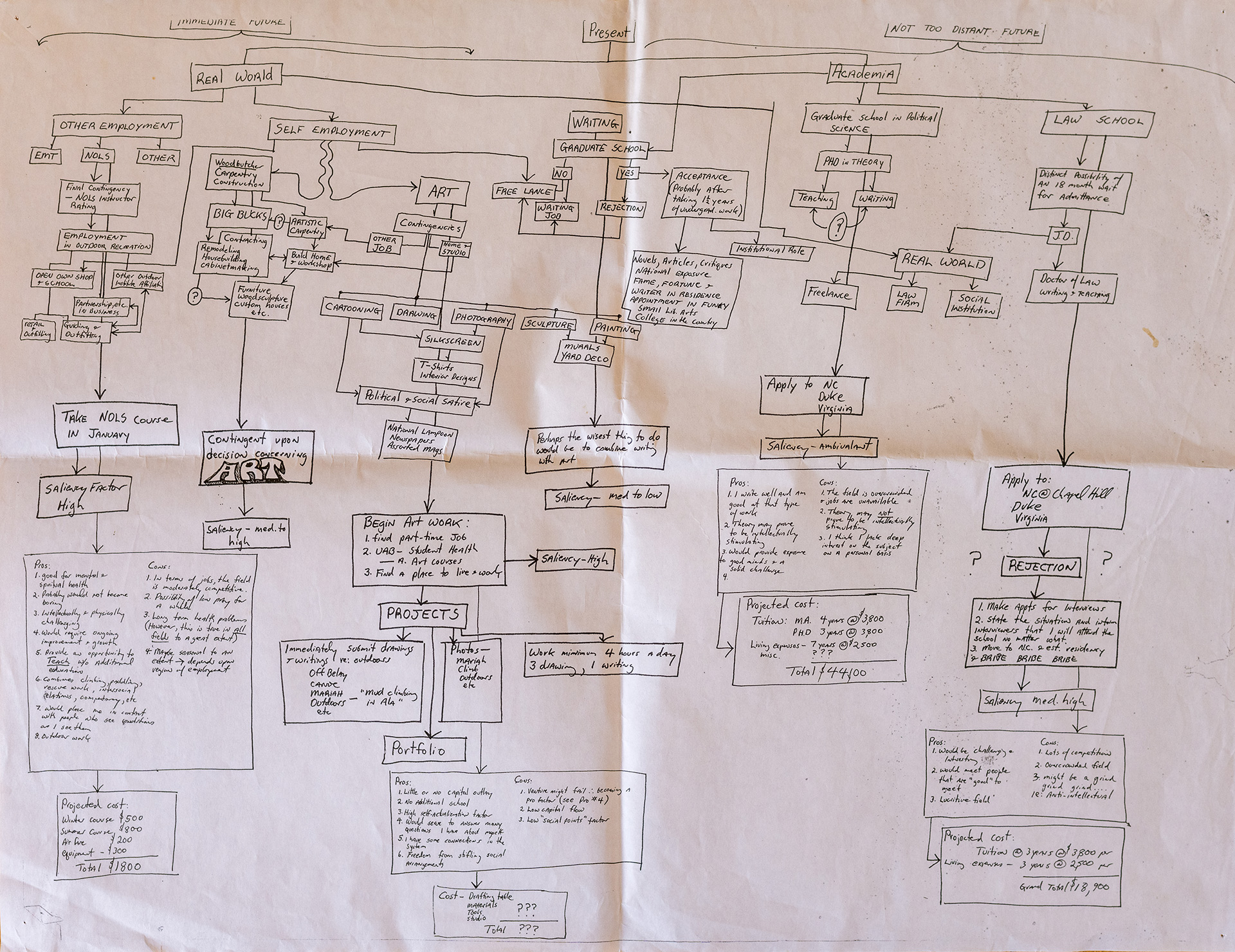

DW: Right. I learned through reading his journals just how much he suffered — how much he suffered not just briefly toward the end of his life, but all of his life. I don't have his journals from when he was a teenager, if he even kept them. And it's possible that the journals I have are the very first ones he kept. And usually, if you begin to journal, as it's called, or to keep a diary, it's usually because you're compelled to by something that is happening to you, which causes you grief and harm. And maybe when he started, he was first realizing what path he was going to be on for the rest of his life. And it was one of an almost constant suicidal ideation. He was truly a man who woke up every morning and had to make that choice consciously.

CR: I want to go back to the time when you were a teenager and he was beginning to influence you. I really related to the discussions you were having with him in those years. And particularly about music, because when I was in my teens, I had a couple of older friends who turned me on to music that I had never heard and also introduced me to certain behaviors that I was probably too young for. But their influence remains such a big part of who I am today. I see a similar dynamic between you and William. When you write about how you would listen to William and your sister, Holly, and their friends through the wall of your bedroom. I mean, I can imagine how powerful that would've been because all of us, when we're young teenagers, are trying to figure out who we want to be like. And you had this whole crowd of people you desperately wanted to be like right there in your house with you. I think I know what it feels like to have, when you're a teenager, an older “mentor into mischief,” if you will. But I can't imagine what it would feel like to have that person actually in the house with you almost all the time.

DW: It was awesome. It was awesome.

CR: How awesome was it?

DW: I had been treated to one way of being and a future that was tacitly laid out for me by my dad, who had this wonderful business which he had started, which would allow me incredible amounts of financial freedom. And that would probably have been where I would've ended up, because I wouldn't have known any other way to be. I feel so many people are depressed because they are in a pursuit or a job that is not suited to them intrinsically, but they don't know what else to do, who else to be.

I had all these aspects of my life provided for me, but just on the other side of the wall, I remember Elton John's “Honky Cat” on the turntable and all of those songs, which I memorized, playing over and over again. Then things like Frank Zappa and Deep Purple. I would never have listened to these people had it not been for their existence in my sister's bedroom. So I could check these boxes of how to be an alternative to who I might have been.

"It was like hanging around with the Avengers. You know that nothing bad is going to happen to you and you know that you're with the absolutely coolest people. And I felt bigger, I felt brighter."

And then later, of course, the drugs became a really big part of it. I did not see them as being harmful, really. So much of my time was spent finding drugs and taking drugs. My life was kind of absorbed by that. I played basketball and played music, too. But the weekend was what I was working toward. Most times, it was scoring LSD or MDMA. Other times, it was out sorting through cow patties, looking for the right kind of mushrooms. This was the natural habitat of William and Holly, just like a vegetarian diet. And I didn't have anybody else. That was another part of it: I didn't have anybody else to share this with. I had no other friend who did exactly what I did.

CR: You write in the book about the night William and Holly took you to your first concert to see Alice Cooper. What was that night like?

DW: I just remember really vividly the crazy, crazy scenes that I was definitely not prepared for or was aware of. But even better, I was with them. And that feeling actually was something that I carried with me for decades. It was like hanging around with the Avengers. You know that nothing bad is going to happen to you and you know that you're with the absolutely coolest people. And I felt bigger, I felt brighter. I felt actually much more special than maybe I was or would've imagined that I was. When they sat by me, one on either side, this incredible osmosis happened, I think. These little splinters of time: how important they can be.

CR: It was a five-plus-year process of you going through William’s journals, right? You write in the book how going through those journals changed you. Can you recall how your own emotional state changed through that five-year process?

DW: He killed himself in 2001, and that began the process of my sister's dissolution. I mean, she was already falling apart. Her prospects were already dim and predictable, but when he abandoned her — or, the way I saw it, he abandoned her — the process significantly sped up. And her life almost in every way was just a process of being in pain. So my feelings for him completely changed, and my admiration disappeared and a real hatred replaced it. It was a very vivid feeling of abandonment for Holly especially, but for me and for everybody. It's much easier for us to judge other people when we don't know them. We don't know who they are. And the process of reading the journals allowed me to understand the totality of who he was and what actually led him to do this.

It’s the worst possible thing you could do to other people. I mean, everybody dies, but not everybody kills themselves. That's a choice that we make. And it's a choice that affects everybody who is close to you. So he didn't cause, for me, sadness. He created a ... gosh … just this darkness and pain. So that persisted. But writing the book, reading the journals allowed me to have the sympathy that we should have for everybody.

People are the way they are usually for a reason. And when we understand that, we can't help but sympathize with them. And that's what the journals really did for me on a day-by-day basis. Understanding vividly and unselfconsciously who he was through his journals, which were written for nobody but himself, I understood how hard it was for him to be alive for as long as he was. That he was able to keep himself alive for as long as he did was probably the most heroic thing he could have ever done.

CR: Let's talk about this unceasing desire to fix things that William always exhibited — from helping you build the frame for the waterbed you got when you were 13 to any of the restoration jobs you recount him doing throughout the book. There was this dark side to that impulse for him. I mean, there's this one passage in the book that really caught my eye, where you wrote, "I think he took the oath of the Scouts and internalized it: ‘to help other people at all times.’ He always tried to make things work. He took on the ballast. This is the gift my family gave him: all that extra weight. Even Holly, the woman he loved, would end up weighing him down. He became earthbound, mortal, and I think that was because of our family." Were you saying there that you believe that William's relationship with your family was ultimately detrimental to him? Or are you trying to get at something else?

"Fixing Holly was obviously an impossible task, but heroes do impossible things. And having knowledge of the impossibility of the task is not enough to disallow you from trying to do it."

DW: Detrimental? Yes. I think psychically detrimental, but not through any desire of our own. Holly did not mean to have all these terrible autoimmune diseases. But William’s vision of who he was in the world was a person who could take something that was broken and fix it. And Holly ... fixing her was obviously an impossible task, but heroes do impossible things. And having knowledge of the impossibility of the task is not enough to disallow you from trying to do it. So I think she contributed, and I really want to be careful in how I say this: She contributed to his final decision, but it wasn't because she was sick. It was because he couldn't make her well. He said it was like watching your lover being raped every day of her life. Our expectation of him was that he could fix things. He fixed everything. And that burden eventually was one of the things … it accreted more information for him — as if he needed it — to die by suicide.

For most of us, our goals are not to look for reasons to die. Usually, we're looking for reasons to live. And he made stabs in that direction, trying to find reasons to live. Holly was a reason for him to live. So yeah, there's that joke. I mean, this may be inappropriate, but it's true: A guy goes to a psychiatrist, and he says, "Doctor, my brother thinks he's a chicken." And he says, "Well, why don't you tell him he's not?" And he says, "Well, I would, but we need the eggs."

CR: Right. Here was this man who defined himself — and could continue living despite the depression he suffered from — by his ability to fix things. And not just to fix things, but to help people who were flummoxed by stuff like how to paddle a particular river or how to ride a mountain bike across five miles of a single track. That's how he defined himself. And it just happened that the one thing on Earth that he could not fix and could never fix was the person he loved more than anything else in this world.

DW: Yes.

CR: I want to talk a little about William’s work, about his books and his maps. After I finished reading This Isn’t Going to End Well, I asked a few paddler buddies of mine if they knew about William Nealy and his maps, and every one of them said yes. Some of them didn't recognize the name right off. But when I described the maps, they were all like, "Oh yeah, that guy, I've used those maps." And the maps and the books I've looked at seemed to me to be amazing expressions of the William that you described in your book. I mean, you look at those maps, and they're just things of wonder. I look at the mountain biking books and they're amazing.

DW: His goal with those books, as you said, was to help other people. I want to say he wasn't a Boy Scout, but he was at the same time. He was a very dark individual on one hand, but on the other hand, a Boy Scout exactly what he was. He could help anybody, but he couldn't help himself. The maps, the books that he wrote were instructional manuals, and they were accurate. They were detailed. They could take you from beginner to intermediate to advanced in the same way that he learned how to do it. Which, if you think about it, is really hard to do. I could not write a book, much less 10 books, on how to become a writer. I mean, every time a writer is asked that question, they just say, "Well, read a lot and write a lot."

CR: Someone called William the “poet laureate of whitewater.”

DW: William showed you exactly how to do it, step by step, moment by moment. Every alternative to what you could do. Nobody's ever done that to this day. I don't even think anybody's actually tried to. His example was such that you know immediately it's impossible to approach what he did. So his river maps, I think if he had only done that, that would've been enough to make him the iconic man that he became. That's where his character, his idea of who he was and how he could share that with other people, really reached its peak. And I watched him draw these maps. It was an intense process that eventually led to his physical demise, just hunched over that drawing board for so long, getting the map exactly how it needed to be. Eventually, he would chain himself to the drafting table so he wouldn't get up and leave and go ride his bike.

CR: Literally chained?

DW: Literally chained around his ankle.

CR: That says something about who he was all by itself. One of the most shocking and moving pages in the book for me was when you discovered this instance from six years before he killed himself, where he wrote in all capital letters, "I must not let them see who I really am." It's hard for many of us to open up in ways that would benefit us. Why was he so afraid to share what he really felt like inside?

DW: I think he hated the William inside. I think that the cool William was the William he wanted the world to see. And I want to make sure that I'm clear in that it wasn't as if the exterior William was false, and the interior William was true. They were both true. They were both real. They both existed. He was bifurcated. He created a persona, which was the one that he preferred and the one that everybody else preferred. We are much less popular when we present ourselves as the truly damaged people we are. We don't do that. I don't do that. I'm sure when you lead with that, it makes it hard for other people to want to be with you.

"Forgiveness is a word we bandy about that we feel is the ultimate expression of understanding and love. I don't think it's forgiveness. I think it's grace."

Everybody wanted to be with the cool Will. But if you don't let anyone see that really scared, fractured, damaged person who also exists, it’s a process of accumulation of terror, interior terror. It's a secret that, as it becomes bigger and bigger, you're much less likely to share. And that leads to the ending that he finally chose. And right after he says that, he says, "I'll never show them who I am because they couldn't take it. They wouldn't be able to take it." But that's so inaccurate. People love us, and people love to help. To finally be in the position where you can do something for the person who has always been doing something for you is a place that we yearn for. Most of us love to save other people if we can.

CR: It's the ultimate expression of the golden rule, really. Right?

DW: Absolutely. Absolutely. But he wasn't comfortable with that.

CR: No, and that's a sad thing, because sometimes in life, letting someone else see the sad, fractured, damaged person inside you is the only thing you can do to save yourself.

DW: Sometimes, I have trouble even showing my wife, who loves me unequivocally, the early stages of my writing. It's an early draft and is inevitably flawed. And I don't want her to think of me in any way as imperfect. All I want is for her to love me. All I want is for her to want me. All I want of her is to think of me as a golden boy. I don't want to do anything that diminishes that. So it's really the same impulse with my writing that he had with his entire existence.

CR: Did the act of coming to really understand William through his journals help you realize the general importance of trying to understand people that we maybe even have hatred for?

DW: It did. And it makes life much more difficult when you know that. My political stance in the world encourages me to hate other people. And I don't want to be that person. I don't think it's necessary to hate other people in order to express a position or to do good in the world. But having that knowledge is not enough. It's not enough for me to assume that people have baggage. You have to prove it to me, as William proved it to me in his journals. But it should be a lesson you could apply it universally. I haven't been able to do that as much as I would want to in a global sense.

Forgiveness is a word we bandy about that we feel is the ultimate expression of understanding and love. I don't think it's forgiveness. I think it's grace. I think it's an acceptance. I don't want to be a source of conflict in the world. I don't want to be a source of hate for people who I have issues with in my life. I just don't feel like there's a reason for it. I don't want to live like that. So I've made efforts with the people who I've experienced less-than-ideal moments to resolve and accept.

CR: How people experience the world is unique to each individual. It gives us different ways of thinking about interacting with each other, with our neighbors. And the only way over the hump with people that you feel divided from is to get a real understanding of what made them who they are. I took that as the universal lesson from your book.

Did you feel like the experience of writing this book transformed you? As an outsider reading it, I concluded that it changed how you look at the world.

DW: I think that question has different aspects to it. As a writer, it’s a process of crafting a compelling narrative from this very difficult experience. Getting into this story, busting into it, was really hard. This is my first book of nonfiction, so I had to learn how to do that. I was starting from zero. I realized that if my journey, my personal journey, overwhelmed me, I could not write the book. I could not write a book that would transform a reader even a little bit.

I'm not interested — in fiction or nonfiction — in whether the writer is going through something while creating this, but you want it to be a work of art. It's only a work of art if it transforms the reader. So I'm really thinking about you more than I'm thinking about myself. As I reflected, though, on the things that I did and the things that William did, I came to an understanding and a clarity which I didn't have before writing the book. A lot of the things that I write about in this book about how William influenced me, I didn't know until I wrote it down.

I wasn't just transcribing my feelings. So it was a real wonderful, educational, illuminating experience for me to write this book because I understood things I didn't understand before about William, about myself, and about other people. That's true. But do I evince that in my own life? No. I can do it on the page. I'm much better at that than I am in my day-to-day life. I'm a much better person on the page.