The Last One Left

Robert Lee Coleman, at 18, led a crew of teenage musicians in Macon, Georgia, who played so hot even James Brown came to town recruiting. At 78, he plays even hotter, and he vows to “play until I die.”

It’s a rainy night in Georgia.

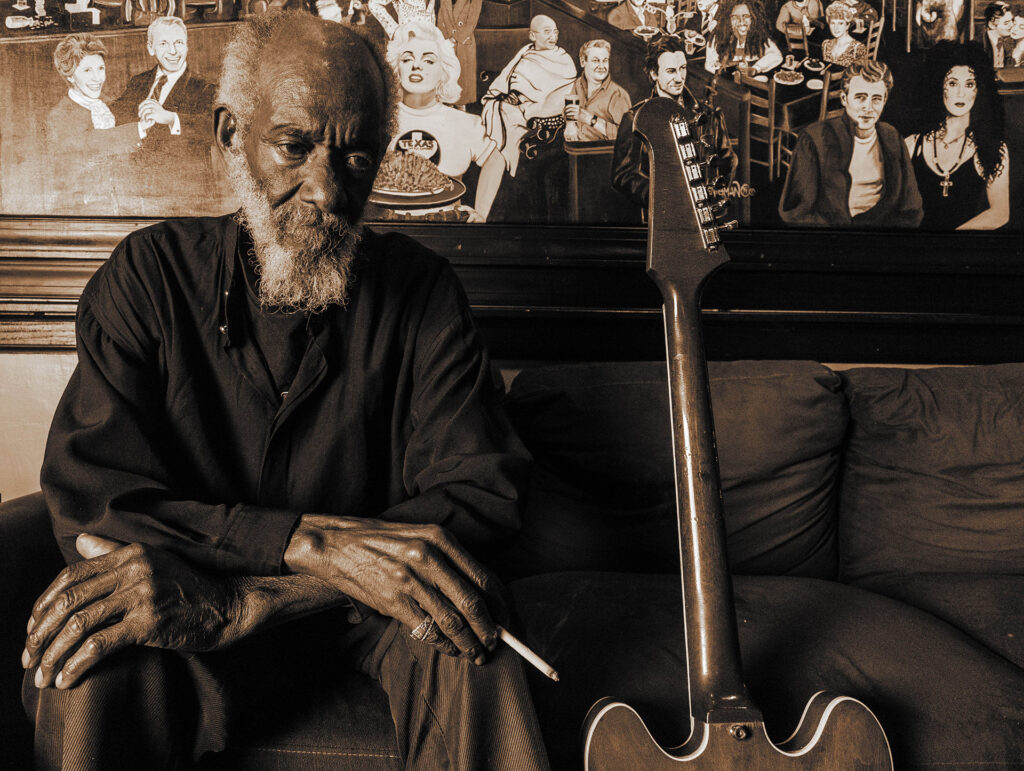

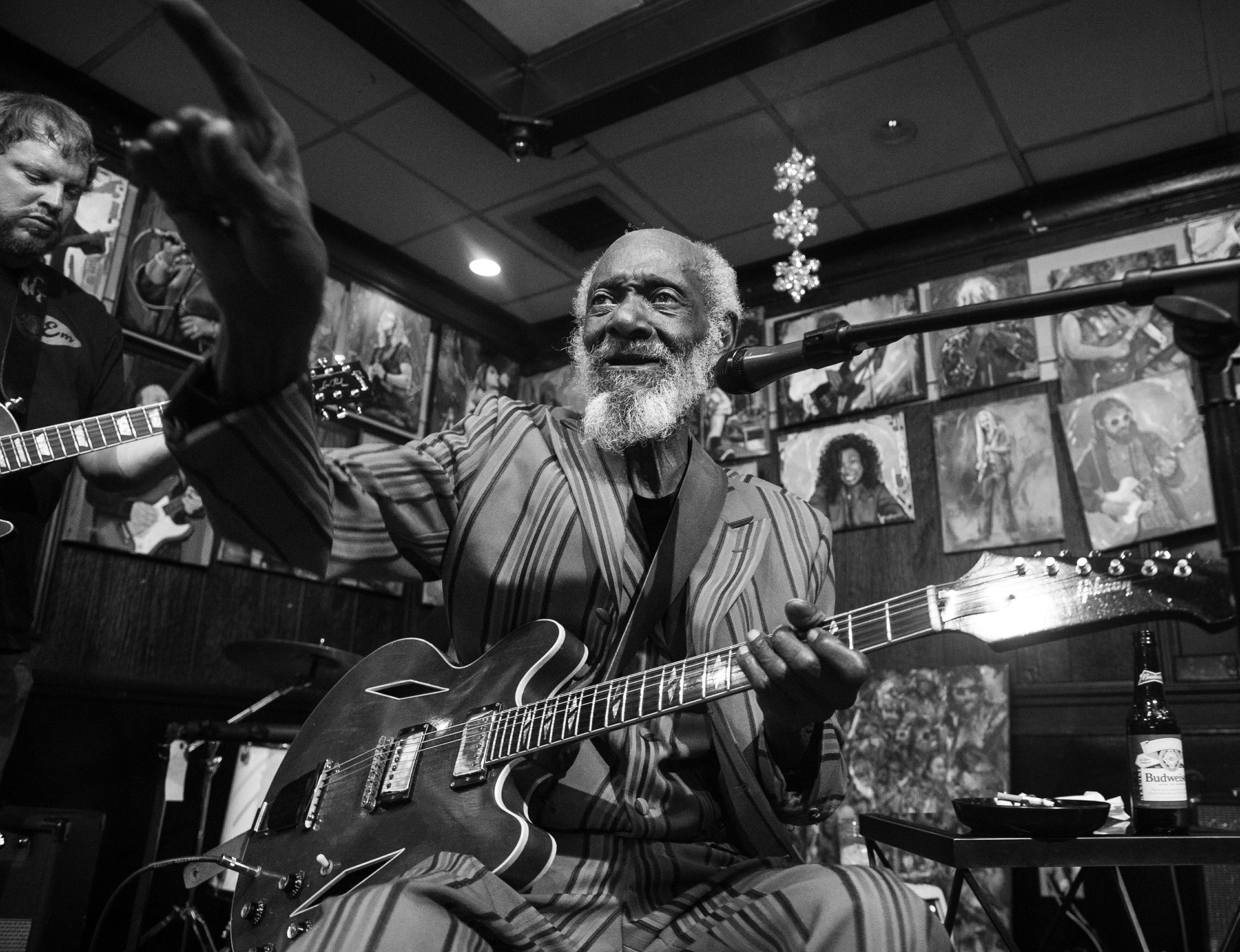

Inside the Back Porch Lounge in the Middle Georgia city of Macon, Robert Lee Coleman, dressed in a red suit with black pinstripes and red shoes, bends a sad note on his Gibson Custom Trini Lopez guitar as he and his band deliver an emotive rendition of Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” the first song in history to top the Billboard magazine Hot 100 chart and its R&B chart.

The groups Coleman led in his teenage years, Underground Railroad and the Firebirds, sounded so incandescent, America’s greatest musicians flocked to this small music mecca to hear and hire them. Coleman and his bands frequently played old Macon joints like The Elks Club, Ann’s Tic Toc Room and Club 15, where Little Richard, James Brown and Otis Redding performed in the 1950s and ’60s.

“We had a band here in Macon and that’s how Percy Sledge found me. All those guys are dead. I’m the only one left.”

“I went out on the road with Percy Sledge in 1964 when I was nineteen and I stayed until early 1970,” Coleman had told me earlier in the day. “Then I went with James Brown in 1970. I stayed with James until 1973. We had a band here in Macon and that’s how Percy found me. All those guys are dead. I’m the only one left.”

Macon, eight-seven miles south of Atlanta, retains a historic musical mojo all its own. Among the Southern music power locations, only New Orleans, Memphis, Nashville, Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and Clarksdale, Mississippi, rival Macon. James Brown recorded a demo of his first hit “Please Please Please” at the WIBB radio studio in Macon in 1955. Hamp “King Bee” Swain, an influential bandleader and DJ in the city’s African-American music scene, exposed listeners to Little Richard—the son of a Macon bootlegger—and James Brown on WBML, a 1,000-watt local station. Swain later worked at WIBB, the 5,000-watt radio station on Mulberry Street where Otis Redding sang “Shout Bamalama” over the airwaves for the first time.

Georgia bluesmen Blind Willie McTell and Rev. Pearly Brown and attended a school for the blind in Macon, and both busked for change on the streets. Ray Charles, born down the road in Albany, enjoyed performing at Macon’s Grand Opera House.

In these fertile musical environs—where gospel, country, jazz, blues, funk, soul and rock ’n’ roll flourished like cherry blossoms—Robert Lee Coleman grew up.

The Back Porch Lounge has operated inside a Best Western motel on Riverside Drive for twenty-two years. Arriving the day before Coleman’s gig and my pre-show interview, I rent a room, drop off my bag, and walk around the building to the bar’s entrance.

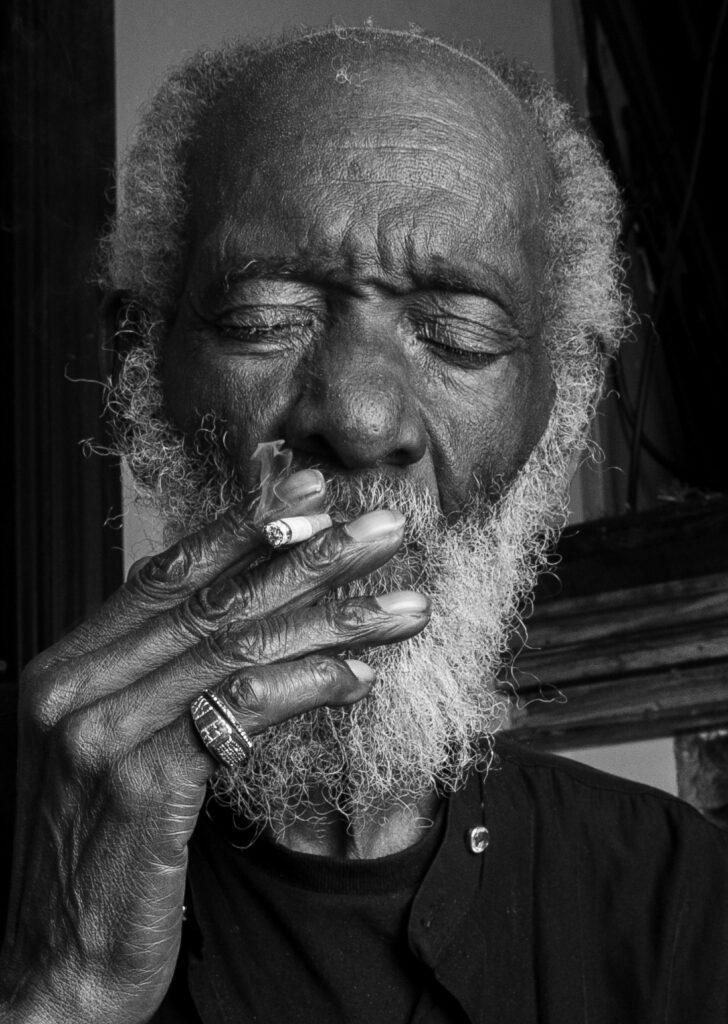

The first person I see when I walk through the front door is Robert Lee Coleman. He’s sitting on a maroon vinyl couch near the door, under an inimitable painting featuring Jimmy Carter, Gregg Allman, Elvis, Little Richard and Otis Redding. Coleman is smoking a cigarette and drinking a Budweiser. Smoking is still allowed at the Back Porch Lounge. I introduce myself and explain over the blaring speakers above our heads that I am the guy here to interview him.

I order a beer and join Coleman on the couch. His white hair and beard give him the appearance of a sage. On this Sunday night, he’s dressed casually in a camouflage Bass Pro Shop fishing jacket, black shirt, and loose-fitting red pants. The music is too loud for a proper conversation, so we just make small talk.

“Who is your favorite country musician?” I ask, almost yelling to be heard over the din. Coleman replies with a grin, “Willie Nelson. I love Willie. He’s so different. Willie is a monster. I opened for Willie Nelson’s son.”

“We’ve adopted Robert Lee,” the Back Porch’s owner, Amy Padgett, tells me. “He’s like everybody’s uncle.”

The Back Porch Lounge is a spacious establishment with a staff that operates like a close family. Dark carpet runs wall to wall. There’s a bar area that leads to the big room with tables and chairs where music is played on a low stage. On this Sunday evening, six or seven guys play cards in the middle of the room. Paintings of Georgia-based musicians created by local artist Angela Henigman line the wall behind the stage. A disco ball hangs from the ceiling.

“We’ve adopted Robert Lee,” the Back Porch’s owner, Amy Padgett, tells me. “He’s like everybody’s uncle.”

Some folks watch an NFL game on the TV behind the bar. A birthday party is underway. The interracial crowd of regular patrons seems to all know one another. I admire a framed promotional poster on the wall that reads: “Adam’s Lounge: Old Gray HWY-Macon Presents ‘Poonanny Be Still’ January 27, 1995. 9 PM Until.”

I feel honored to drink a beer with the man who co-wrote “Hot Pants” with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul.

The following day, hours before his Monday night show, Coleman and I sit by the Back Porch Lounge pool tables to talk. Robert Lee Coleman was born in Macon on May 15, 1945. As with so many great African American musicians, his love for music started in church. His stepfather played guitar. I inquire if he was the typical eight or nine years old when he showed an interest in musical instruments.

“No, I was smaller than eight,” he says. “I don’t quite remember when I bought my first guitar. It was hard times back then. I think my mama bought it. I used to crawl up under the bed. The bed was sitting kitty-corner, so it left a triangle in the back. That’s where my stepdaddy kept his guitars. I’d crawl under the bed and get back there and I’d be messin’ with the guitars.”

His stepfather didn’t teach him, per se, but Coleman learned the instrument at his knee.

“He was the best player I’ve ever seen,” Coleman says. “He could sit there with a guitar and do all the blues like Muddy Waters and Lightning Hopkins. He used to listen to the radio and play the theme songs—or TV and play the songs right back. They tried to get him to record. They said they’d pay him to record, and he wouldn’t do it. He liked to play house parties every Friday, Saturday and Sunday. He used to take me with him sometimes.

“Any time he grabbed the guitar at the house, I’d sit down cross-legged in the living room and watch him play. I wasn’t even in school yet. I’ve never had one lesson in my life.”

“He never said, ‘Boy come here and let me show you. Do it like this.’ Never. But he was the best,” Coleman continues. “He had a sound like all the country players, blues players like Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed. He used to play it all. He never showed me anything because any time he grabbed the guitar at the house, I’d sit down cross-legged in the living room and watch him play. I wasn’t even in school yet. I’ve never had one lesson in my life.”

Coleman mastered his instrument early. Percy Sledge came looking for him in Macon, hired him, and took him on the road. He was already in Sledge’s band when “When a Man Loves a Woman” hit No. 1 in 1966. With Sledge’s band, Coleman traveled the United States, Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa.

“We had a band here in Macon, and that’s how Percy found me,” Coleman says. “And now all those guys are dead. That’s why I named my (2018) record What Left. Percy [first] came here and got some horn players, and they went out on the road with him. Then I went out on the road with him; they came back and got me in 1964.”

Coleman played with soul legend Sledge from 1964 to 1969, then joined the JB’s, the backing band James Brown founded in 1970, after he split with his 1960s band, the Famous Flames.

“I just got a shot,” Coleman says. “James needed a guitar player.”

Coleman also wound up co-writing one of Brown’s most famous hits, “Hot Pants.”

“‘Hot Pants’ was my lick. I created that,” Coleman says, then takes me back to how the Godfather of Soul worked with the JB’s—a huge band—in the studio.

“James told you what to play,” Coleman recalls. “He’d come up to you and hum what he’d want you to do. As he’d hum I’d pick it up. For the Hot Pants album, James lined up the horn section, and the drums were set back. He always kept two or three drummers. There were thirteen of us lined up. He’d start with (trombonist) Fred Wesley, and he’d tell the horn section what to do. I was standing about midway, but I was ready by the time they got to me.

“I listened to what everybody was doing, and I had that lick,” Coleman says. He hums that instantly recognizable part to me.

“You got to be sharp to keep up with James. James Brown was a Taurus, and I’m a Taurus, too, so we got along. James made the publishers give me credit for that song. He told them, ‘That’s Robert Coleman’s lick.’ They had to redo the label for my credit.”

Coleman gets jazzed talking about what it was like to play on stage with Brown, a masterful bandleader who infamously could cue his players to change course with just the slightest movements.

“James would be dancing and you gotta keep your eyes on him. When he’d drop his hand everybody had to keep his eyes on James,” Coleman says. Following Brown’s direction, he says, was “the easiest playing I ever did.”

“You got to be sharp to keep up with James. James Brown was a Taurus, and I’m a Taurus, too, so we got along.”

“I’ve been playing on that stage [points to the Back Porch Lounge stage] for seven years,” he says. “Every Monday. I play harder on that stage than anything I ever did with James Brown. See, with James you’ve got to play parts. I was the lead guitar player. So, I might just play one note in a song, and that’s all James wanted to hear.”

Arthur “Bo” Ponder grew up with Coleman in Macon and played with him during the 1960s in Underground Railroad and the Firebird—and, as Ponder puts it, “ten or more” other bands.

“We were like brothers,” Ponder says. “We’d been together since we were twelve years old. We wrote songs that we’d hand off to other folks. We got ripped off on some of them. We had no knowledge of the music industry. We were happy to have people play our songs. If we made two or three dollars a night, we were fine. All our friends were great musicians. By the time we were sixteen or seventeen, we were some of the baddest guys around.”

He recalls the core group of young musicians who floated in and out of those teenage bands: Clarence Lucas, Calvin Arline, Newton Collier, Waline King, Nancy Butts, Gloria Walker, and others.

“The big time folks started to come and hear us,” Ponder says. “Next thing you know, they pull some of us out. Percy Sledge grabbed Robert Lee Coleman. Bobby Womack grabbed Arline and the horn players. Newton Collier played with Sam & Dave for fifteen years. Then James Brown came and got Coleman. If we would’ve stuck together—we couldn’t because we were too poor!—we’d have been big.

“Back in those days, Macon was the bomb. You never knew who you were gonna meet in Macon. We all knew Little Richard. James Brown was born in Augusta, but his home was Macon. Everybody was coming to Macon in those days.”

“Back in those days, Macon was the bomb. You never knew who you were gonna meet in Macon. We all knew Little Richard. James Brown was born in Augusta, but his home was Macon. Everybody was coming to Macon in those days.”

He remembers well when Brown recruited Coleman into the JB’s.

“Robert Lee’s playing blew James Brown’s mind!” Ponder says. “His playing blew James away. James said, ‘I’ve got to have that guitar player.’ Coleman talked with us about it, but we said, ‘Go make that money.’ He did.

These days, Ponder says of his old friend, “Coleman has become quieter. He’s really humble, but he’s one of the best guys you could meet.”

I ask Coleman why he left the JB’s in 1973, only three years after joining. His answer is simple.

“I got tired,” he says. “The road is hard. It’s nothing to mess with.”

In 2009, Coleman began a still-going association with North Carolina’s Music Maker Foundation, which since 1994 has been dedicated to assisting music pioneers with food, shelter, medical care, instrument acquisition, recording and touring. In thirty years, Music Maker has assisted over 520 artists.

Coleman has recorded two albums for Music Maker, One More Mile (2012) and What Left (2018). One More Mile, recorded in Huntsville, Alabama, contains all original material, with one exception—a killer rendition of Atlanta musician Theodis Ealey’s “Cookie Jar.”

What Left, recorded in Athens, Georgia, combines blues, funk, and jazz into one potent brew.

Touring with the Music Maker Foundation, Coleman has performed in France, England, Australia, and in big-name music festivals across America, such as New York’s globalFEST, the Telluride Blues & Brews Festival in Colorado, and the Roots N Blues BBQ Festival in Columbia, Missouri. When gigs were unavailable because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Music Maker provided financial assistance to help Coleman ride things out until he could resume playing life.

Tim Duffy, Music Maker’s co-founder and executive director, says the important thing to know about Coleman is simply “that he exists.”

“Guys like Robert were the first generation of musicians playing the electric guitar and bringing it out to the world in Black clubs and recording with these big singers getting it out to the white world,” Duffy says. “He’s an impeccable sideman. Percy Sledge and James Brown, they needed Robert’s sound to make that music. They could’ve had anyone, but they wanted their own guys.”

Duffy met Coleman through a mutual acquaintance who invited Duffy to watch Robert Lee Coleman sit in with Los Lobos at the Roots N Blues BBQ Festival in Missouri.

“Guys like Robert are the real secrets to American music history. It still exists, but it’s getting harder to find.”

“So, Robert plugs in and plays the whole set with Los Lobos, and he just tore it up!” Duffy recalls “Afterwards, Los Lobos was like, ‘If Robert came to East L.A., he would rule!’ Robert can get down and jam. He was trading licks and playing note for note with their lead guitarist. Robert can play with anybody. Eric Clapton? Whoever? Bring ’em on. They can’t take Robert. Robert is a real player. He can scare you to death.”

And Duffy is not at all surprised that Coleman is still playing his regular gigs in Macon and at festivals across Georgia.

“Robert is still playing music because he loves it,” Duffy says. “He’s a very shy guy. He’s used to being a sideman. He doesn’t like any attention on him. It’s not his thing. But onstage, he does.

“Guys like Robert,” Duffy concludes, “are the real secrets to American music history. It still exists, but it’s getting harder to find.”

John Mollica, a visual artist in Macon who has created album covers, posters, and merchandise for acts including the Allman Brothers Band, and Gov’t Mule, helps Coleman with booking and management. At the bar, I ask Mollica what Coleman represents to him.

“It’s the real thing. There isn’t a whole lot of that around,” Mollica says. “That’s the main thing for people to know. He just loves to play. It doesn’t matter if there’s two people or two thousand. On any given day, he’s the best guitar player in Macon and beyond. He’s great. At seventy-eight, he still puts his time in, and he still believes he’s learning. He’s not spitting out the same old thing, which is really cool, because he acts like a mentor to all the young players. There've been a lot of great players that have grown up here that have gone on to bigger gigs. A lot of them played in Robert’s band. For young players, it’s important to interact with guys like Robert Lee.”

Listening to Mollica describe Lee’s method brings to mind jazz legend’s Miles Davis’s saying, “It’s not the note you play. It’s the note you don’t play.”

“Robert leaves so much space it will make you uncomfortable,” Mollica says. He knows what not to play. You have to be really patient if you’re playing with him. You can’t be nervous about space as a guitar player. Robert leaves a lot of breathing room. Every note he plays is valuable. He never wastes a note. He doesn’t overplay. He’s real sparse and real good. You have to play many years to learn that.”

Mollica recalls a recent encounter Coleman had with the 25-year-old blues prodigy from Mississippi, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram.

“He came to Macon to play a gig at the Capitol Theater,” Mollica says. “He’s a student of old blues. He sold the Capitol out. Robert played an after-show party at Grant’s Lounge. We told Kingfish about the gig. He ends up showing up with his whole band. Kingfish stayed up there with Robert the whole night. They just tore it up. It was cool to see the kid soaking up the greatness of Robert Lee Coleman. Kingfish didn’t act like a star who was gonna save the show—he just played with Robert. It was great to see the young and old blues worlds converge.”

It’s good that the young blues world comes to Coleman because he can’t really spend much time touring these days.

“I got so many other things in my life,” he tells me. “I have to take care of my lady. She’s blind. I take care of her. When we first started going together, she had eyesight. When she lost it, I couldn’t just pack up and go. God would not appreciate me leaving her like that. You know what I’m talking about? She can’t see. I can’t leave her. I take care of her every day.”

Still, the music reaches for him every day.

“I just keep doing it. I can’t stop,” he says. “The minute God takes that guitar from me, I’m through. I can play on that guitar even when I’m at home.”

He says he has no regrets.

“I think music kept me out of trouble,” Coleman says. “I was always on the stage. I don’t have any regrets about my career.”

“I just keep doing it. I can’t stop. The minute God takes that guitar from me, I’m through.”

At the Back Porch Lounge on this rainy Monday, he leads his young band through “It’s a Mean Old World,” “It Feels Like Rain,” “When a Man Loves a Woman,” “Sweet Home Chicago,” and the Elmore James classic “Done Somebody Wrong.” Coleman hypnotizes everyone with the electric magic that flows from his amplifier. Smoke floats in the air, drinks flow, and people dance.

As Robert Lee Coleman strums his final notes, I feel lucky to hear him up close, and melancholy watching him wave goodnight, then step off the stage. I remembered what he had told me that afternoon:

“I’m gonna play until I die. I could be down by the Ocmulgee River, and I’ll still be playing. I just play.”