Unstuck in Pasaquan

A trip to St. EOM’s Pasaquan shrine is worth your time anytime. But on one Saturday this September, it was the hippest place in the cosmos.

EDITOR'S NOTE: After an endless summer of rambling from the Dust Tracks Heritage Trail to Yoknapatawpha County to Elvis’s manger, your Culture Warrior was bone-weary and ready to watch the autumn leaves go straight from green to brown to ignore on the ground. Then a late-arriving email from International Anthem records set him on the road again.

—Chuck Reece

Chicago artist and musician Damon Locks—whom I covered here and there in 2022—and artist/composer Rob Mazurek were slated to perform the following day in Buena Vista (pronounced BEW-nuh VIS-tuh), a town of 1,585 (down from 2,173 in 2010) in southwest Georgia that is smack dab in the middle of bumble. My fellowship with falling foliole would have to wait. How I suffer.

It might seem odd that two of Chicago’s finest—plus Brooklyn-based jazz stalwarts Kenny Wolleson and Kirk Knuffke—would play such a tiny outpost, but Buena Vista is the home of Pasaquan, an “internationally recognized visionary art environment” (as the website puts it) that was hand-built over several decades by the self-taught artist Eddie Owens Martin, aka St. EOM. Pasaquan is not just back of beyond: it’s on top of, beside, and underneath beyond.

Born to sharecroppers in Buena Vista in 1908, Eddie Owens Martin had a hard childhood. Growing up gay in the rural South of the early twentieth century was no picnic, a situation made worse by a notably abusive father. He ran off to New York City at age fourteen, making his way as a fortune teller, gambler, con man, drug dealer, and, primarily, sex worker. During this period, he experienced one of a series of visions that would drive his life’s work. As he explained to writer Tom Patterson, a voice told him, “You’re gonna be the start of something new, and you’ll call yourself St. EOM, and you’ll be a Pasaquoyan—the first one in the world.”

Or as Martin himself told me in late 1985, “I heard a voice, and that voice said ‘Go home!’ and I said ‘What?’ and it said ‘Go home!’ so I went home and built this place, just me and Sherwin Williams.” (It turns out he had a fair amount of help, but why ruin a good story?)

Over the following decades, St. EOM (pronounced “ohm”) created his shrine to the Pasaquoyan pantheon, a life’s work that is now recognized as one of the world’s finest examples of visionary art. But it was not always so. When I first visited in ’85, Pasaquan was deteriorating apace with its creator’s health. On our uninvited arrival he threatened to sic his German shepherds on my beloved Stanwyck; she scrambled back into the car just ahead of the dogs, who then attacked our battered Datsun. Eddie came up yelling about trespassing and such. It was not looking good.

“I heard a voice, and that voice said ‘Go home!’ and I said ‘What?’ and it said ‘Go home!’ so I went home and built this place, just me and Sherwin Williams.”

The vibe was akin to the two short visitations I experienced with Sun Ra, another astral messenger in service to expansive creative visions. St. EOM vibrated on a different wavelength than we did, so we shut up and tried to make sense of what he was trying to tell us. Bottom line: the cosmology Eddie described encompasses a pantheon of benevolent deities who wish us all to partake of the creative impulse and imagine a better and kinder way of living this limited time flash we call a life. By that time, the German shepherds were licking Stanwyck’s hands, and Eddie was making a serious dent in our cannabinoid offering.

He was clearly unwell, and his animated storytelling soon took its toll. He shooed us from the house but granted permission to walk the grounds for as long as we liked. We wandered for more than an hour. Some walls and sculptures were crumbling by then, the chipped and fading paint lending some faces a cockeyed gaze that suggested dismay at their own decay. But the grandeur of St. EOM’s vision was clear.

All in all, it was an energizing encounter for a couple of city kids who had driven in circles for several hours trying to find the place. (We succeeded only after a woman frying chicken at a nearby gas station heard us asking; “they’re looking for old crazy Eddie,” she said without turning around.) But as lucky as we felt, we also worried that we might be among the last to see this place before it went the way of Ozymandias.

Six months later, news came that Eddie had taken his own life. About a year later, Tom Patterson published a gorgeous volume, St. EOM in the Land of Pasaquan: The Life and Times and Art of Eddie Owens Martin, a book that is thankfully back in print. (Buy it now. Go!) Word spread about St. EOM and his paradise garden. But the place was falling in on itself.

Over the next two decades, folklorist Fred Fussell and his wife, artist Cathy Fussell (a Buena Vista native who had known Eddie since childhood), drove a crusade to preserve Pasaquan. In 2007, the site was named to the National Register of Historic Places, just one year after it landed on Georgia’s Top Ten Places in Peril list. The Society reopened Pasaquan to the public on a limited basis in 2008, but the outlook was grim.

Salvation arrived in 2014 when the Fussells landed a multi-million-dollar grant from the Kohler Foundation to preserve and restore Pasaquan. Subsequently, Columbus State University took ownership of the site and folded it into its museum operation. In 2016, Pasaquan reopened to the public with a gala celebration headlined by Colonel Hampton. A fleet of buses carted visitors to the property from the Buena Vista town square, chipper tour guides telling stories that reduced this unorthodox astral messenger to somebody’s kooky uncle.

Fortunately, the site’s caretakers have resisted the urge to buff Eddie’s legacy into a Disney-esque caricature. Pasaquan remains resolutely weird in the very best sense of the word, and the renovation is just spectacular. The colors are vibrant, the structures and sculptures lovingly refinished. Gone are the cockeyed visages facing their imminent demise. These deities are ready to serve the cosmos.

Go see for yourself. Just two hours south of Atlanta, a visit to Pasaquan is a day well spent.

But this day in September was different from all other days.

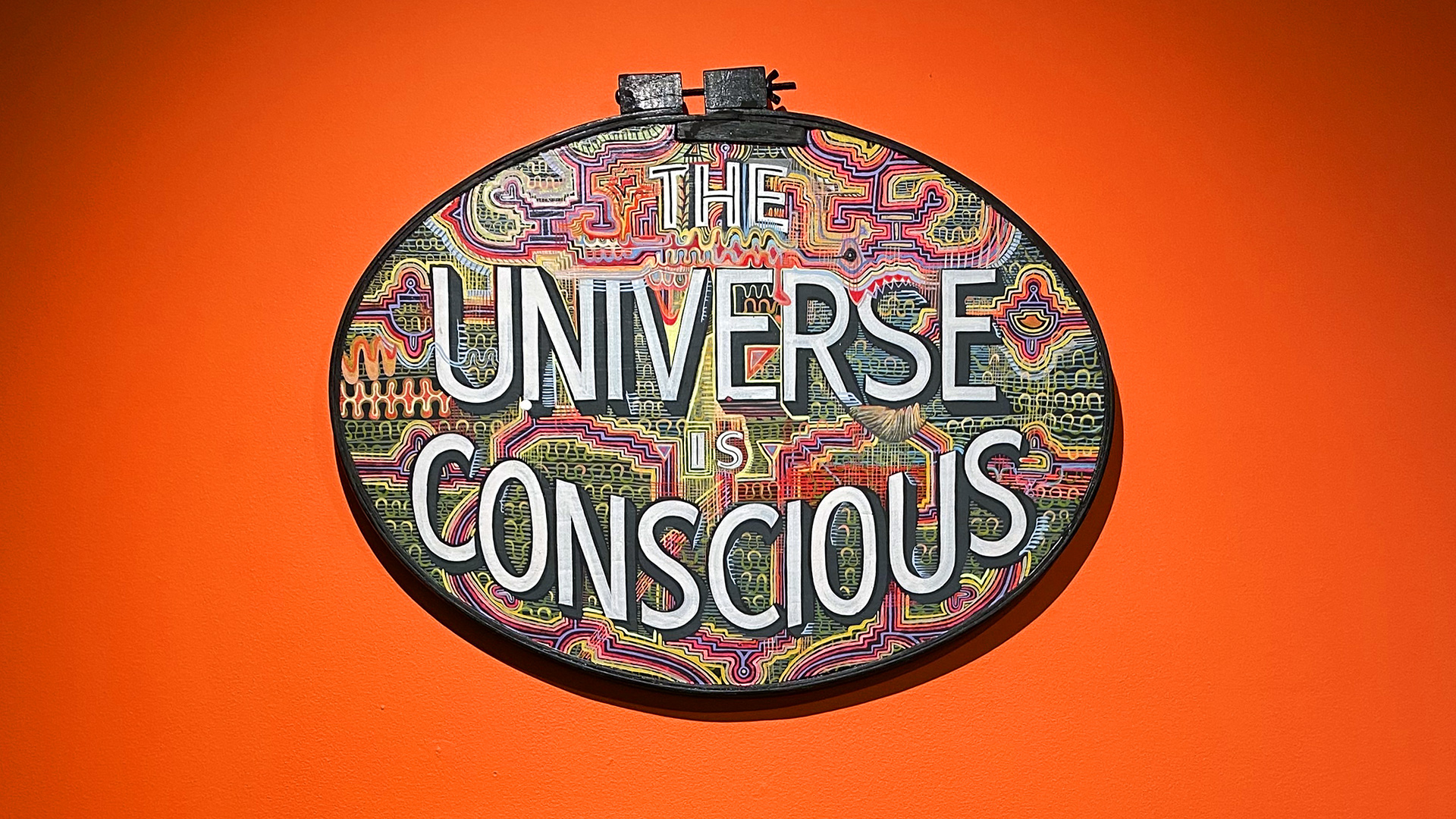

In the before-COVID time, CSU Professor of Art and Director of Pasaquan Mike McFalls approached the Birmingham-based art collective Fuel and Lumber to curate a show of contemporary artists for a joint exhibition called “Unstuck in Time” at Pasaquan and the Bo Bartlett Center, a gallery on the CSU campus. Amy Pleasant and Pete Schulte of Fuel and Lumber set out to assemble artists whose “work shares a uniqueness of vision, radicality, determination, dedication to craft, and a deep belief that art can not only speak to the human condition in the here-and-now, but that it might in fact be a conduit to help us imagine new worlds and possibilities.”

“We wanted to connect the distant past to the present and future. It’s the kind of thing Eddie would have loved.”

Professor McFalls put it this way: “We wanted to connect the distant past to the present and future. It’s the kind of thing Eddie would have loved.”

There’s no debating that premise. In Patterson’s book, St. EOM explains, “I found out later that pasa means ‘past’ in Spanish. And quoyan, I found out, is an Oriental word that means ‘bringing’ the past and future together. So you can derive the benefits of the past by bringin’ it into the future. And that’s why I call myself a Pasaquoyan, and this place is called Pasaquan.”

Fuel and Lumber recruited eleven visual artists to present work in conversation with EOM’s vision of bridging past to present, ancient to future. The exhibit at the Bo Bartlett Center (on view through December 16) includes a wide range of EOM’s creations alongside the curated artists, whose work was also on display at Pasaquan. The exhibit opened at Bartlett the evening of Friday, September 15, followed by a daylong celebration at Pasaquan on Saturday.

I visited the gallery on Saturday afternoon, after most folks had gone to Pasaquan. I had plenty of room to wander and double or triple back to consider how certain pieces seemed to call to one another. It was a thrill to see Eddie’s work again, and the curated artists offered a vital reflection of his inspired inventions.

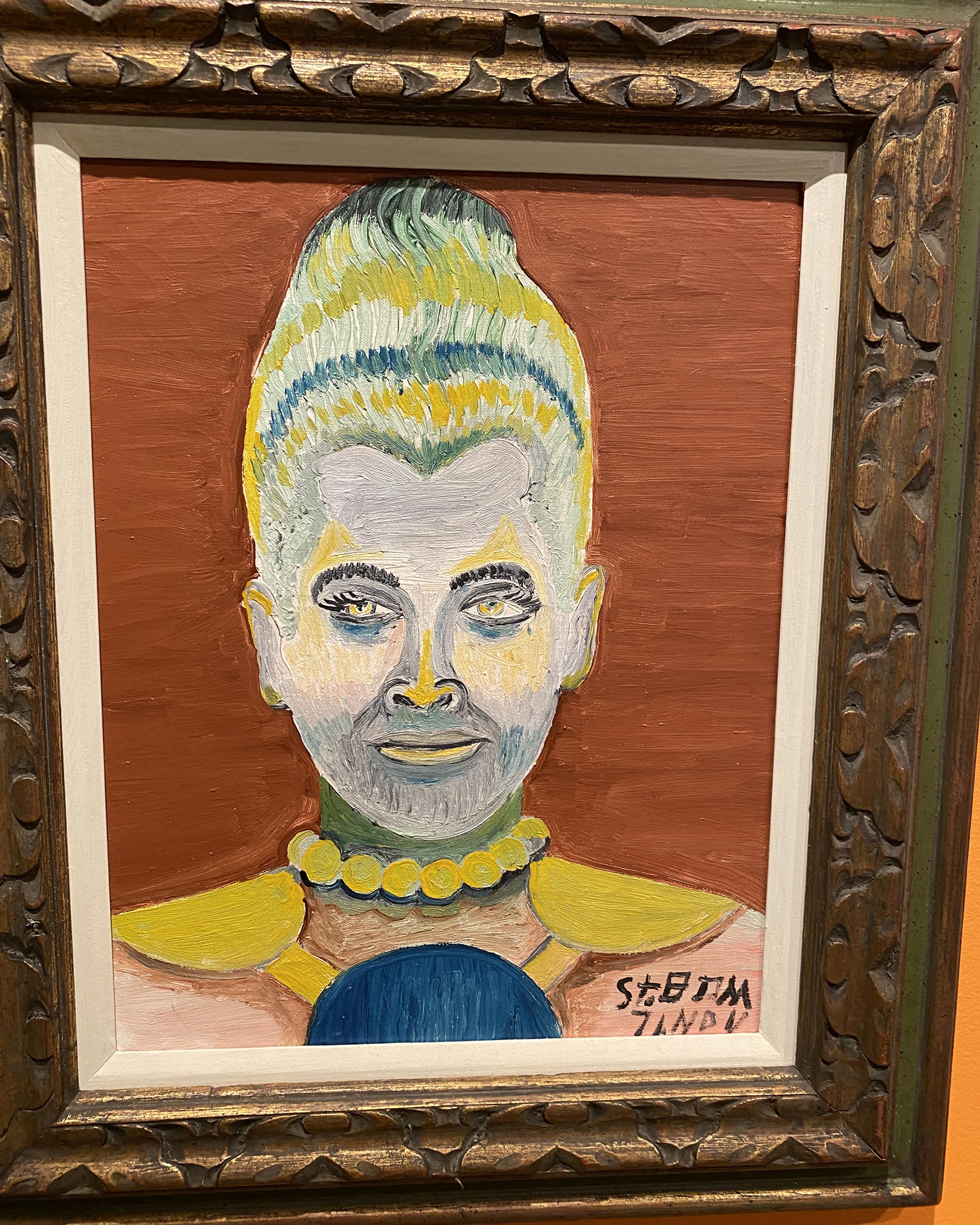

Sonya Yong James’s piece, Nothing Gold Can Stay, resonated so strongly with the central role of hair in St. EOM’s cosmology that I was sure it was one of Eddie’s pieces. James, an Atlanta-based textile artist, creates work that examines the ways myths and fairy tales are “fragmented and conflated with another to form new clusters of meaning.”

Chime Choir by artist Julia Elsas also perfectly captured EOM’s vibe. From a distance, it looked like fringe fabric that you might hang above a doorway, but a closer look revealed hundreds of clay chimes so delicate it seemed they might flutter in a light breeze.

Currently based in Brooklyn, Elsas grew up in Birmingham before earning her MFA at the University of California, Davis. Her work encompasses printmaking, drawing, sculpture, painting, and performance, but ceramics appear to be her primary medium, one that dovetails nicely with her interest in performance.

“Most of my three-dimensional work grew out of my ongoing exploration of the sonic potential of clay,” she explains. “I consider my sculptures to be fully realized only when they are being played.”

Her vehicle for getting these instruments played is the improvisational music ensemble Sonic Mud, whose first album landed a week ahead of the Pasaquan hoolie. Living in Brooklyn has its advantages, among them proximity to adventuresome professional musicians like Wolleson and Knuffke who are open to collaboration with what Brian Eno calls “non-musicians” like Elsas.

Sonic Mud performed on Friday to a gallery crowd of several hundred, and again on Saturday where I joined a smaller audience squeezed inside the Pasaquan house. With St. EOM’s murals as backdrop—and the sun’s autumnal angle twinkling kaleidoscopically in the windows—Sonic Mud delivered gently flowing explorations of the sonic possibilities inherent in the various drums, shakers, and wind instruments. One of these was tonally reminiscent of the Jewish shofar, fitting for an event that began on the first night of Rosh Hashanah and right in line with Elsas’s ongoing exploration of Jewish identity in much of her work. Wolleson and Knuffke’s professional understanding of improvisation complimented the more intuitive probings of Elsas and architect Madeleine Ventrice Knuffke for a set that perfectly captured St. EOM’s esotericism. Occasionally tribal, frequently evocative of birds and insects, Sonic Mud’s flits of gossamer melodies floating over pulsing rhythms were purely organic.

This cut from the new album gives an idea.

Then we moved outside in a shift from organic past to electric future.

Damon Locks is a visual/vocal/electronica artist widely known for his creative collective Black Monument Ensemble, which made two of my favorite albums of the past five years. Composer/cornetist/filmmaker/artist Rob Mazurek calls himself an “abstractivist” and is perhaps best known as the leader of Exploding Star Orchestra, an absolute banger ensemble that includes Locks on voice and electronics alongside a who’s who roster of Chicago’s best musicians.

Locks and Mazurek released their first duo album last July under the name New Future City Radio (see where we’re going?), a shape-shifting collage of noise, melody, poetry, rants, and sonic what-nots in the “programmatic format of a pirate radio station.” It’s the kind of thing that could drift into muddle or pretension in lesser hands, but it is a beautifully coherent trip that, in the words of the album’s liner notes, “contemplate(s) community, transformation, and the future.”

Kinda like Pasaquan.

The duo performed outdoors to a couple hundred folks amidst the pagodas, brightly colored walls, and panoply of Pasaquoyan deities. The ‘stage’ was a slightly elevated circle filled with sand and ringed by a foot-high wall adorned by EOMian colors and geometrics, more ritual dance ring than traditional performance platform. It didn’t hurt that it was the first Saturday south of the gnat line that did not feel like a malfunctioning sauna. The air was dry, with a mild breeze verging on cool. The sun was sinking like a ship, the insects warming up for a long night’s chirp.

After an hour of traveling the spaceways, the duo made their way through and around the crowd, eventually disappearing into one of the pagodas as their looped soundscape carried on, Mazurek’s occasional cornet peals slipping out the windows just as the sun disappeared behind the tree line.

Curator Pleasant explained later that “our goal was to assemble a group of artists and work that felt in sync with the occasion and opportunity [and] that also had the potential to create resonances with the spirit of St. EOM, Pasaquan, and the world that he created and inhabited.”

But the best laid plans and all that jazz, right?

“We feel that what happened during the opening weekend in Georgia had very little to do with us,” she told me. “Everything seemed to coalesce beyond our wildest dreams and take on a life of its own. It turned into something meaningful and real, something vital that is sadly lacking in the ‘Art World’ as we so often experience it. Honestly, we still feel overwhelmed and just so incredibly grateful to have been along for the ride.”

“Everything seemed to coalesce beyond our wildest dreams and take on a life of its own. It turned into something meaningful and real, something vital that is sadly lacking in the ‘Art World’ as we so often experience it.

Me, too.

It’s one thing to declare a resolve to create something that matters. But all the hard work and good intentions in the world (and the Pasaquan and Fuel and Lumber teams poured heart and soul into this project, even during the uncertainty of pandemic) are no guarantee that the Creative Impulse will embrace your aspirations. You do the work, make the arrangements, and show up to give it your best shot. It might turn out pretty good, or even very good, but the juice that boosts an endeavor up into that next level of vibration is largely beyond our volition.

The Fairy Dust landed on Unstuck in Time to bring into being a miraculous tracing of the Creative Impulse across time and space. The combination of the musical performances and the exchange between Eddie’s works and the curated artists described an ancient-to-the-future arc that we are well advised to consider on the daily. In a world where attention spans are allocated in nanoseconds, consciously connecting to our befores and afters may be the single most radical practice we can exert to slow the world’s careening spin into fractious disarray. Events like Unstuck in Time are gifts to remind us of this; we are well advised to pay them heed.

My apologies to the many artists I am unable to mention. They are critical to this immersive experience, but this article would be a book if I delved into all the creators involved. Please go to the Bartlett Center and see for yourself.

By the way, that remote place on an unnamed dirt road that we could barely find thirty years ago has an address now: 238 Eddie Martin Road, Buena Vista, Georgia, 31803. It’s a damn sight easier to find these days, though I must admit I miss those watchdogs.

Go. Listen. Look. Absorb.

About the author

Chattanooga-based writer/musician Rob Rushin-Knopf, Salvation South’s longtime culture warrior, blogs about culture at Immune to Boredom and appears regularly as one-half of the near-jazz duo RoboCromp.