Inside the Wonder

Jim Crow dumped its worst on Lonnie Holley. But his globally recognized music and art prove how beautifully he survived the belly of that beast. Just don’t call him an “outsider.”

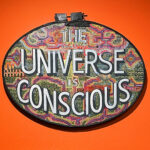

“I am a part of the wonder.”

— Lonnie Holley

Everybody loves an uplifting underdog tale about a plucky striver who overcomes impossible odds and shows us how to make lemonade and turn frowns upside down. America especially craves that triumph-of-the-human-spirit thing when it offers a side order of atonement for the nation’s original sin. Soothe me, brave hero!

From a comfortable remove, multidisciplinary artist Lonnie Holley checks all the boxes to satisfy our craving for a heartwarming, pull-up-your-own-bootstraps saga. But Holley’s Deep South origin story bespeaks horrors that make the darkest imaginings of Charles Dickens seem downright tame by comparison and render any feel-good voyeurism more than a tad problematic.

Consider: Born in Alabama in 1950, the seventh of 27 children, Holley was stolen from his mother by a burlesque dancer who then traded him away, when he was only 4, for a bottle of booze. Beaten daily by a foster dad, he ran away from home only to be struck by a car and declared brain-dead. But wait! He experienced a miracle recovery, only to be returned to foster care.

So he ran away again.

The state declared Holley incorrigible and imprisoned him in the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children at Mount Meigs, where the kids picked cotton when not enduring floggings and ongoing sexual abuse. He was eventually released. Then, at age 15, he fathered the first of his 15 children and began working a string of menial jobs to survive.

Quick cut to 1979: His sister’s house burned down, her two youngest children — a son and a daughter — dying in the fire. Unable to afford gravestones, Holley scavenged a chunk of sandstone from a foundry junkyard and fashioned the markers himself. It was his great awakening; the Sand Man was born.

“Outside of what? What am I outside of? Outside of prettiness? Outside of beauty? That hurts me to be called all these names. I have worn these titles like ill-fitted suits."

Ever since, Holley has devoted himself to alchemizing trash into treasure, building an epic body of work that has made him a bona fide art star, albeit one who does not always receive the respect he has earned. His drawings, sculptures, and photographs reside in some of the world’s most prestigious institutions and collections (the United Nations, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Gallery of Art among them). Earlier this month, Holley posted photos on Facebook of himself with United States Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman to serve on the Court. (She had asked for a painting on loan to hang in her chambers; instead, he presented her with a painting he created specifically for her.) His art is revered at the highest levels of achievement, and Holley has reportedly attained an estimated net worth somewhere north of the million-dollar mark along the way.

Yet somehow, the derisive “outsider art” tag still clings to him like a wet shirt. While not quite as sniff-sniff insulting as the inherently supremacist “primitivism” label it replaced in art-critic shorthand, the term remains a hallmark of the arrogant gatekeeper bullshit wielded to keep the uncredentialed rabble in their place.

But just a few minutes in Holley’s company underscores that, despite the privations of his early years, he is far from primitive (or naïve, yet another quaint attribute implied by “outsider”). A man of incisive intelligence, Holley understands exactly what the world around him means and how it works, and his creative choices reflect a sharp sensibility and strategy for confronting our condition.

I ask him about that outsider label.

“Outside of WHAT?” Holley erupts. “Outside of what? What am I outside of? Outside of prettiness? Outside of beauty? Outside of an established brain? I just did what I did. That hurts me to be called all these names. I have worn these titles like ill-fitted suits. I've been called more things than you want to even imagine just because of what I'm working with. What I'm working with, man, I'm working with all the way down to the nitty gritty, to the grit of the gritty, to the particles.”

Though he'd begun making music in 1980s, Holley began releasing his music to the public in 2012 with the album Just Before Music (Dust to Digital=). While his entire back catalog is worth a listen, his sixth album — MITH (Jagjaguwar Records, 2018) — was a landmark release that made multiple Best Of lists. The single “I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America” accompanied one of the most compelling music videos you will never see on MTV. Think of it as something of a response to the call of Childish Gambino’s “This is America” video released the same year. Or maybe vice versa.

Along with the global reach of his visual art, Holley performs all over the world. He never repeats himself; every concert is something new – he jots a list of potential song titles to trigger his stream-of-consciousness creations – with a rotating lineup of backing musicians reacting in the moment to whatever pathway of memory and inspiration takes his fancy.

On March 10, Jagjaguwar released Holley’s seventh album, Oh Me Oh My, a simmering cauldron of Gil Scott Heron’s biting sociology, Sun Ra’s outer spaceways, and the deep, off-balance groove of electric Miles Davis. There’s a sanctified gospel vibe central to the whole affair, as the title track (with R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe singing backup) demonstrates.

The album is a richly layered collage that recalls the 1981 David Byrne/Brian Eno classic My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Like that sonic landmark, Oh Me Oh My is an assemblage of bits and pieces, not unlike Holley’s visual artworks. But where “Ghosts” built upon sampled vocal tracks of pirated shortwave broadcasts and assorted talk radio gasbags, producer Garret "Jacknife" Lee uses Holley’s spontaneous vocalizations as the foundation for elaborate studio constructions, with guest turns from the likes of Stipe, Malian superstar Rokia Koné, and Sharon Van Etten.

Two tracks with on-fire Afrofuturist musician/poet/activist Camae Ayewa, aka Moor Mother, are especially effective; the contrast of Holley’s timeless past and Moor Mother’s infinite future vision perfectly articulates the wonder Holley insists that we all carry within us.

Holley’s sense of wonder holds “Oh Me Oh My” in one hand and “Fucked Up America” in the other in an act of pure love, blossomed from his embracing a universe of contradiction and pain, deciding all the same to be thankful for every day, as expressed in this track featuring Justin Vernon of the band Bon Iver.

Greatness will come in the morning

And kindness will follow your tears

And dry them up

Down through the years— “Kindness Will Follow Your Tears”

Befitting an artist who creates his work in direct engagement with his surroundings, Holley is no studio hermit. Much of his practice finds him engaging with people who may not recognize their potential as creative human beings. Holley is on a mission to awaken us to the wonder and to reassure us: Even though things are indeed fucked up, we hold the power to reclaim the grace and beauty that is our birthright.

“Seek and you shall find, like the Bible says,” Holley says emphatically. “Look for opportunity instead of just sitting around, depressing yourself or depriving yourself even further. I call it the quicksand fields of stupidity. If we sit around and act stupid, then stupid shall we be.”

This spring, Holley will spend a week in Knoxville, Tennessee, as an artist-in-residence at the Big Ears Festival where he will perform at least twice. (Last minute surprises at the festival are standard operating procedure.) He has a couple of pieces in the first Tennessee Triennial for Contemporary Art at the Knoxville Museum of Art (through May 7) and a solo exhibition of recent sculptures, paintings, and works on paper at the University of Tennessee Downtown Gallery (through April 2). The gallery will also run ongoing showings of short films about the artist.

“Look for opportunity instead of just sitting around, depressing yourself or depriving yourself even further. I call it the quicksand fields of stupidity. If we sit around and act stupid, then stupid shall we be.”

Perhaps most significantly, Holley will be a keystone of the Big Ears Festival’s community engagement activity, a growing and substantial component of the Big Ears effort to integrate their local community into its globally situated programming. (I wrote about the 2022 CE program for Salvation South here, here, and here.) Holley will spend festival week mentoring kids in the public school system and sculpture students at UT’s School of Art.

Especially intriguing is what a festival press release describes as an “on-site creation of a found-object sculpture in collaboration with local students and community members” under Holley’s guidance. Big Ears Community Arts Director Rachel Milford informs me that this project will take place during the Friday and Saturday street party at Knoxville’s Historic Southern Railway Station. This segment of the festival is open to everyone at no charge.

Last year, New York Times journalist Marcus J. Moore ordained Holley as the “heart” of the 2022 Big Ears Festival, a calm eminence grise dispensing soft-spoken wisdom to a parade of festival artists who made special effort to visit with a revered elder. Big Ears founder and executive director Ashley Capps echoed Moore, noting that “his presence and work magnifies and illuminates all that Big Ears hopes to be.”

“Lonnie Holley stares down the darkness that surrounds us [and] creates paths that open us all to beauty and the mystery of life itself,” Capps tells me. “He is a remarkable visionary, but one deeply rooted in the essence of everyday life and community. He is an omnivorous collaborator — with other great artists and musicians, certainly, but also with young people who are just starting to make their way through the world.”

I ask Holley what he plans for the young artists of Knoxville.

“Human needs nature. Human needs outings. Human needs field trips. And that's what I want to do with the students."

“I already got my bag of material that I'm going to demonstrate,” he says. “I got some stuff already put together in my bag, and I'm gonna do the same thing I was doing years ago as the Sand Man.”

And that means getting out into the world.

“Human needs nature. Human needs outings. Human needs field trips. And that's what I want to do with the students. Take them out of the classroom and let them gather the materials that they are going to be working with. And we're going to put our hands in it. We may need a box of gloves for the kids who don't really want to get their hands in it, but I’m all about putting my hands in it. I want to touch it.”

He relates a recent event that shows how these field trips might work.

“We went to eat the other night,” he explains. “They had cut this tree, cut down to the stump. And there was a hollow part in the stump. The roots were growing up through that hollow part of the stump. I pulled out some of that root and some of that dirt. And man, I took that and made one of the most wonderful looking little pictures. It was a woman. It was a woman, and she was standing, and she was praising. But under her feet were these roots that I had pulled, and they were growing, moving the earth underneath our feet.”

“All these things give me inspiration.”

Even where Holley’s work is gorgeously transportive — Oh Me Oh My is chock full of sonic and lyrical transcendence — his dedication to diving “all the way down to the nitty gritty, to the grit of the gritty” prevents easy escapism from inconvenient realities. Holley has paid a high price for his initiation into the “wonder,” but despite it all, he remains committed to sharing his “part of the wonder” with anyone willing to accept the gift. But it is a gift that becomes ours only if we pay the price of honest reckoning. Admitting to only the happy parts of our histories guarantees we will remain mired in the “quicksand fields of stupidity.”

Any frisson of delight we might derive from Holley’s rags-to-riches trajectory stands in sharp relief against his savage suffering under Jim Crow. It is a history Holley cannot forget — refuses to forget — and he insists we remember it, too. At this moment, when schoolteachers in my home state of Florida are at risk of prosecution for teaching this history, this witness is especially profound.

Outsider my ass. Lonnie Bradley Holley is America, inside looking out and showing it to us with discomfiting clarity.

Go. Listen.

About the author

Chattanooga-based writer/musician Rob Rushin-Knopf, Salvation South’s longtime culture warrior, blogs about culture at Immune to Boredom and appears regularly as one-half of the near-jazz duo RoboCromp.

I’ve just seen some of Mr Holley’s wonderful artworks at the Royal Academy in London, where they are part of an exhibition called ‘Souls grown deep like rivers – Black artists from the American South’.